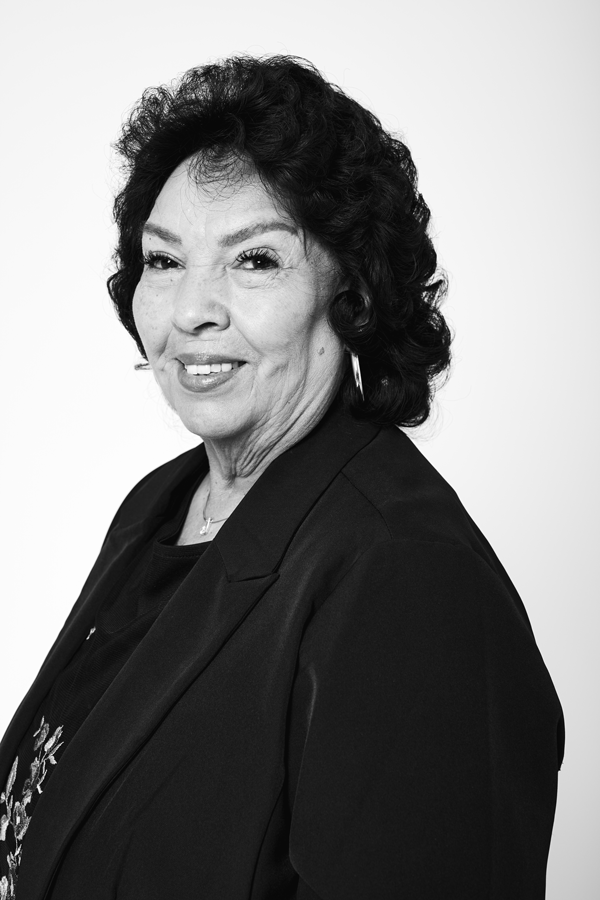

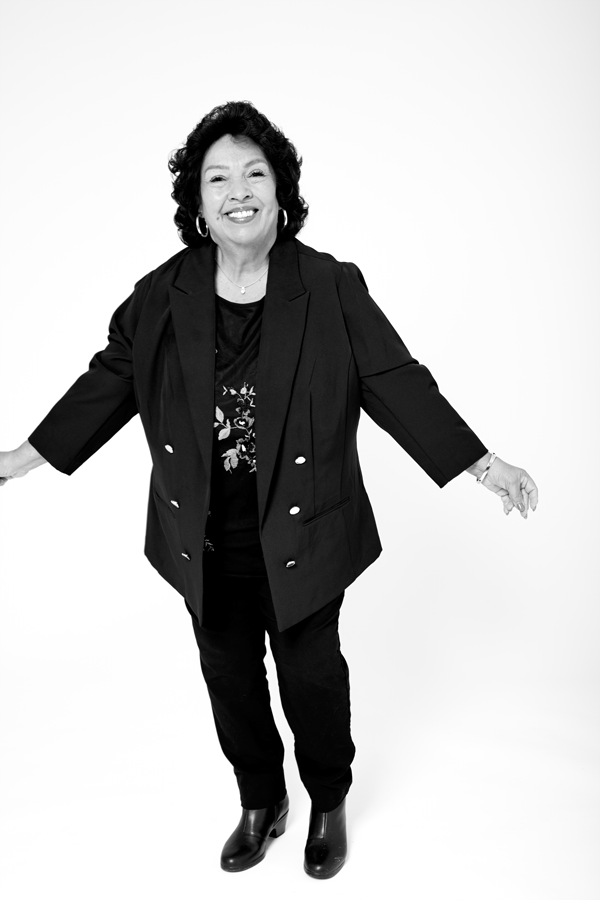

Betty Aragon-Mitotes

Founder, Mujeres de Colores

Co-founder, Museo de las Tres Colonias

The drug dealer pointed a thumb and forefinger at Betty Aragon-Mitotes, and the message was clear: Go away or I’ll shoot you.

Before she came back home to Fort Collins to take care of her ailing father in 1996, she likely would have looked down at her shoes and walked away, the way she did as a young girl growing up in north Fort Collins when others made fun of her neighborhood, what some called “the barrio,” or posted signs that said “No Dogs or Mexicans” in front of their businesses. That girl risked a failing grade in her classes rather than get up in front of her fellow students and give a presentation. She would freeze up even at the thought of it.

But things had changed since she first left the area. Her childhood neighborhood had been overtaken by drug dealers like the one who threatened her. She thought of her father, whose health problems stemmed from working the mines in Trinidad so that his family could have a better life. She thought about how the booming cars kept him up at night and how she was afraid to leave her porch.

She got the drug dealers’ attention by starting a petition to get the police to patrol her area, and her fearful neighbors admitted, quietly, that they were scared as well. But something rose up inside her when the dealer pointed his finger at her. As a girl, others saw her home as the barrio, but she saw it as Buckingham neighborhood, a safe place where her community gathered when no one else would have them. She felt she needed to protect it the same way her neighbors once protected her.

“Do it,” she said to the dealer. “Take me down right here.”

Betty Aragon-Mitotes. Photo by John Robson.

The petition eventually forced the police to patrol the neighborhood, and they caught the lead dealer in a massive drug bust. That was the end of it.

Aragon-Mitotes, a shy Latina woman who worked for a jeweler and a bank before returning home, had protected her neighborhood and the people who lived there, including her dad. She realized she needed to start speaking up.

“I needed to be the voice for those who are voiceless,” she says now.

She’s devoted her days to doing just that by producing three films: one on racism in Fort Collins, another about the plight of immigrants during the pandemic and a third on the history of the sugar beet workers in Northern Colorado. She’s been recognized as a leader in the Hispanic community and has won more than a half-dozen awards, including the Polly Baca Raíces Fuertes Community Leader Award she received from Rep. Joe Neguse in 2023. In 2016, she formed Mujeres de Colores, a nonprofit that supports low-income families through children’s programs and Hispanic culture education. In 2001, she co-founded the Museo de las Tres Colonias, a museum honoring her culture, which is one of her favorite achievements.

She loves the museum because it showcases the history of her people in Fort Collins and the role they’ve played in the city’s economy and its diversity. Hispanic people were a large part of the sugar beet industry—you can see where the factory stood from the front door of the museum—and they helped form the city’s current status as one of the best places to live in the U.S.

Aragon-Mitotes says that without her efforts and those of others who keep that history alive, her culture would likely be swept away. She points to the Buckingham neighborhood where she become an advocate as an example: Fort Collins’ stifling housing prices have led to the gentrification of Buckingham and many other historic places like it.

“When that happens, the history of that neighborhood, and its significance to my people, is forgotten,” she says. “It’s why I’m so passionate about it.”

Betty Aragon-Mitotes. Photo by John Robson.

She has taken some flak for her efforts, she says, from those who thought she was divisive, though no one has pointed a finger at her in the shape of a gun again. She says she’s learned to be resilient, like her people, and grow a thick skin. Her work doesn’t go unnoticed, says Dr. Becky de la Torre, vice president of Mujeres de Colores.

“She is the face of our Hispanic community,” de la Torre says.

But Aragon-Mitotes is grateful for the partnerships she’s formed with others from all backgrounds, including many white people who helped her with the museum, her films and her nonprofit.

“Preserving one’s culture doesn’t mean you are excluding others,” she says. “I’m proud to bring people together to learn about our Hispanic history and proud of the community that’s embraced what I’ve done. Today I am proud of my brown skin.”

Still, she calls Fort Collins a work in progress. She’s working with the city to get a monument built honoring Latino baseball teams from the 1930s, but she’s had some pushback on that, which frustrates her. In 2021, she campaigned for, and eventually unveiled, “The Hand That Feeds,” a sculpture dedicated to the sugar beet workers in Sugar Beet Park. It was a great moment, she says, but it’s the only one she knows of in the area that’s dedicated to people of color.

Regardless of what happens with the monument, she will produce a fourth film on the Latino baseball teams. Just like the time she stared down a drug dealer, she knows that sometimes you have to take matters into your own hands. At least she now knows many people stand with her.

“One person once said to me, and it made me cry, ‘I see you,’” she says. “But I know that people hear me.”

Ginger Graham. Photo by John Robson.

Ginger Graham

Owner, Ginger and Baker

Ginger Graham prefers not to refer to Ginger and Baker as a restaurant. She likes to call it a community hub.

Pie, she says, reflects those values. It’s something people share, like the love, ideas and conversation people enjoy over food. It comforts heavy hearts after a funeral and decorates the table of those showing off their new home. Graham enjoyed pie made by her mother, who owned a bakery and candy shop, while growing up on her parents’ Arkansas farm. That’s the kind she had in mind when she opened Ginger and Baker in 2017 in downtown Fort Collins.

The business couldn’t help but flourish and grow, just like Graham’s career as one of the top female healthcare executives in the world (among her many accomplishments was a brief, recent stint as the interim CEO of Walgreens). Ginger and Baker earns its title as a hub, with hungry patrons and an array of baking and cooking classes stuffing the building like a meat pie, not to mention the dozens of employees gently excusing themselves as they woosh off to their next task. But there was a time when Ginger and Baker was a labor of love more than a stalwart: Perhaps it was even something for Graham to do in her new community to keep her hungry mind sated while her husband, Jack, ran Colorado State University’s athletic department.

She breathed life back into a historic mill, and eventually the area around it, by building a new structure as well as renovating the old one where Ginger and Baker now sits. At the time, the downtown Fort Collins spot was a little downtrodden.

“We were here way ahead of its time,” Graham says of the 300 block of Linden Street. “But we wanted to influence the area in a positive way.”

She had faith in the mill, which was the kind of gathering place she envisioned, and in her love for Fort Collins. Ginger and Baker was more than a dream of a little pie shop she shared with Chef Deb Traylor: It was an extension of her belief that in order to be a resident of a place, you need to be part of a community.

“I love this community,” Graham says. “It has academia, local businesses, agriculture, innovation and natural resources, and you have to be conscious of that and have a commitment to it. If you want to be a part of Fort Collins, jump in and be a part of it.”

Her hub, which includes The Cafe restaurant, the teaching kitchen and the market and bakery on the main level and The Cache restaurant upstairs, isn’t the only way she shows her love of Fort Collins and its treasure trove of natural resources. She and Jack have a farm, another relic she brought back to life, and they plan to work it until they die. Ginger and Baker, she says, is another way to support agriculture and buy local.

She and Jack also donated $1 million to the city’s Poudre River Whitewater Park, which rescued the project from a deadline that could have ruined all the progress the city had made to restore that section of the river. The couple has lived in many different cities, Graham says, and one thing she loved about them was their connection to their rivers. It always made her sad that Fort Collins didn’t have access to such an obvious asset. When residents can interact with a natural resource, she says they tend to support it.

“It was just a brilliant idea to make Fort Collins a better city,” Graham says. “But they were desperate for that last stage, and all that work would not have been accomplished. It was something we needed to do. It was a huge investment in the community.”

The couple had the means to do it, partly as a result of Graham’s career as a healthcare executive. She is proud of that work and loves being a pioneer in what was, and may still be, a man’s world. Healthcare is her calling, she says, and it’s something everyone needs. If she can make it better, she believes she makes the world better.

Being a woman prevented her from her first love, caring for horses, while working as a large animal vet—”I wasn’t welcome,” she says—and there were, of course, other times when being a woman made her career in the healthcare field hard. But she likes to acknowledge that her gender helped her as well.

“I was always the first,” Graham says, “and when you’re the only woman CEO, you get asked to speak at a lot of conferences. I do think there were opportunities because of that.”

Ginger Gaham. Photo by John Robson.

Graham, to her credit, made the most of them. When she was the CEO of Amylin Pharmaceuticals, it was rated as one of the top 10 places in the industry for scientists to work. When she helped run Guidant, the medical company was recognized by Forbes as one of the best places to work in America. World Pharmaceuticals listed her 10th in its list of the top 40 most influential people in the industry. Graham continues to teach at Harvard, where she got her MBA with distinction after graduating from the University of Arkansas.

She also refuses to take herself too seriously.

“There’s this aura around CEOs,” Graham says. “I’d say it’s 20 percent fabulous and 80 percent ridiculously bad.”

Graham’s personality makes her approachable despite being a world leader in an important field, says a friend, Mark Weaver, who is the president and lead coach of Open Door Organizational Solutions in Fort Collins.

“If you meet her there,” Weaver says of Ginger and Baker, “you’ll think of her as the warmest, most genuine person you’ve ever met. And you’d probably never know the other things she’s done besides Ginger and Baker.”

One of Graham’s favorite accomplishments isn’t really hers, though she helped raise money for it. Jack, as CSU’s athletic director, helped bring Canvas Stadium to the college campus, something Graham strongly believes will help boost the pride students feel about attending the school.

That takes her back to the commitment and love she feels for Fort Collins. She will likely not retire anytime soon; she says she needs the intellectual stimulation work provides her. Solving complex problems remains one of her favorite ways to use her brain.

But whenever she can, she helps run Ginger and Baker, a place that reflects her deep roots. She can still feed 20 at the drop of a hat, she likes to brag, but you get the sense that she’s helping to nourish a whole community.

Chris Haug & Lynn Bassett. Photo by John Robson.

Chris Haug

Founder, The Music Man DJ / Organizer, Greeley Blues Jam

Lynn Bassett

Owner and director, Dance Factory

Lynn Bassett and Chris Haug wept at the pastor’s words as they exchanged wedding vows.

“You can’t dance,” the pastor said, “without the music.”

The two seemed to recognize that from the start of their relationship in 1990, when they were in their mid-30s. Bassett visited The Finest record store in Greeley a bit too often to buy albums and maybe talk to Haug, one of the store clerks who called himself “The Music Man,” the moniker he used as a DJ. Haug didn’t want to ask her out because she was a customer. Bassett solved that puzzle by looking him deep in the eyes and telling him she was going to a Denver club one night. He showed up.

The two have since raised three daughters, paid off their home and become one of Greeley’s most important couples in its thriving art scene.

Haug DJs nearly every major event in the area, including the NCMC Turkey Trot, the Greeley Chamber of Commerce’s annual dinner and school dances. When the city discontinued its father-daughter dance, he took it over, and he’s putting on his third dance this spring. His blues jam at the Chipper’s Lanes bowling alley gives musicians a place to play, and he recently took over the Greeley Blues Jam from Pam and Al Bricker, an annual festival that gathers blues fans for world-renowned music.

Bassett started the Dance Factory in Greeley in 1973 out of her parents’ basement, where it operated for three years before moving to the basement of a travel agency and eventually to its current location in 2000. The Greeley Arts Legacy inducted Bassett into its Hall of Fame in 2023, calling her studio a “manifestation of her lifelong love of dance, family and community.”

Haug and Bassett seemed destined for their place in the arts since Bassett taught dance from the time she was in elementary school and Haug began working as a DJ in 1985. But that wasn’t really the case.

Bassett wanted to be a professional dancer, but her parents forced her to attend the University of Northern Colorado, where she got a degree in recreation and opened the Dance Factory as a compromise of sorts. She thought she was the best teacher (she blushes with embarrassment when she says that today) and wanted her students to have a place to go. But it took her years to find the same satisfaction in teaching that she did dancing at a semi-professional studio or during her summers in Los Angeles.

“At some point, I realized that was my destination in life,” Bassett says of teaching dance.

Chris Haug & Lynn Bassett. Photo by John Robson.

Haug worked other jobs for years while freelancing as a DJ, but around 2019, Bassett told him to stop worrying about making money and start doing more of what he loved. Since then, he’s worked full time as The Music Man, though he says a lot of his time goes into Greeley’s blues scene.

“I don’t make a million,” Haug says, “but I love doing it.”

Bassett’s taken a select troupe or two to dance competitions since 1976, and she’s had five professional dancers start in her studio, but that isn’t really the point, she says.

“We always want to give our kids more than just dance,” Bassett says. “We want to give them life skills.”

The couple’s legacy comes from the families who have been through Greeley. Haug’s done generations of weddings in some families, and Bassett can’t go anywhere without knowing someone from her studio, he says. Bassett was stunned at being inducted into the Greeley Arts Legacy’s Hall of Fame, but it also made her feel proud.

“I hadn’t realized all that I had done,” she says.

Bassett seems content to let two of their daughters run the studio more every day, and Haug admits that many of the people he knows in the business are retiring. Still, Bassett says she’ll never stop teaching (she teaches four classes a day), and Haug says he won’t stop playing music.

When the couple reflects on their time in the arts, they prefer to talk about each other. Bassett says Haug is everywhere still, and Haug says Bassett’s Hall of Fame induction was “long overdue.” He talks about the Dance Factory like it’s their business, not just hers.

“My girls are awesome kids because of dance,” he says.

He continues to sing Bassett’s praises, and she lets him lead, with twirls of her own about his career. The pastor was right when they said their I do’s: You can’t dance without the music.