Before she revamped downtown Windsor’s master plan, Michelle Vance rebranded the organization she now leads. She called it the Windsor Downtown Alliance (WDA). Then she set about to earn the name.

Calling themselves an “alliance,” rather than an “authority,” as they were before, meant Vance had to convince Windsor residents to join it. That was a tall order since, in January 2023, residents petitioned and then soundly rejected a plan to bring a multi-story apartment complex downtown.

But Vance was ready. She formed a steering committee made up of people who disagreed with each other over the contentious issue. She met with more than 200 people over three months. She gave away $1,000 in gift cards to folks lined up for the Windsor Harvest Festival Parade just for filling out a quick survey. She collected more than 500 survey responses at events and online. She admits it wasn’t always fun.

“I ate a lot of dirt,” Vance says, “and I don’t mind it.”

She now believes, after all that listening, that she has a master plan nearly everyone will like, as well as other “what-if” scenarios that could, in theory, increase the value of downtown Windsor by millions of dollars.

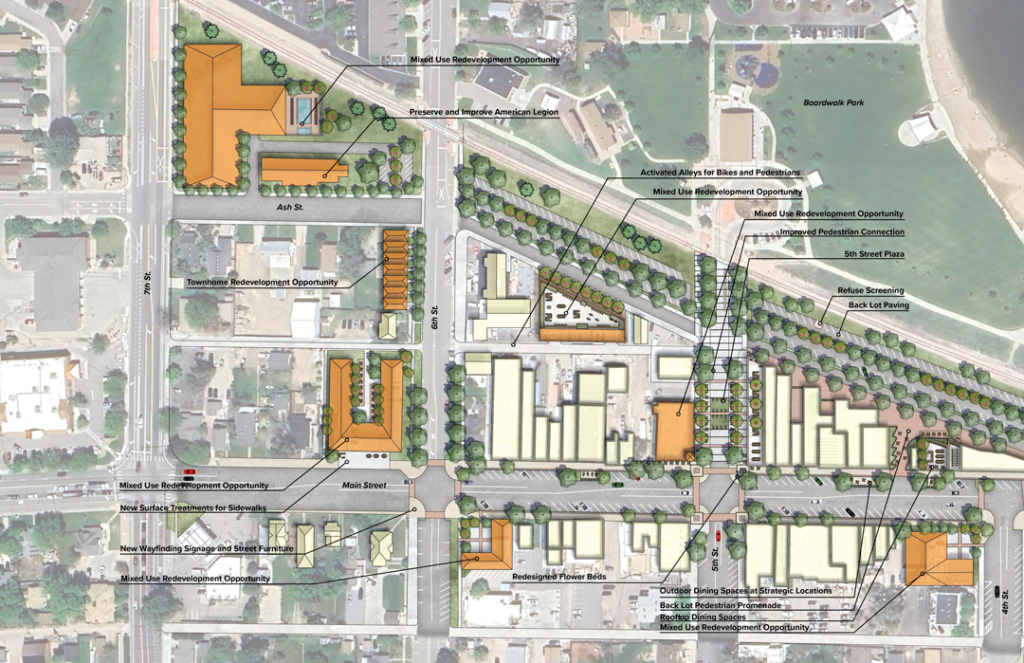

This rendering is for illustrative purposes only and represents a potential idea for redevelopment at this location. No redevelopment or acquisition of the property is planned. Courtesy of Town of Windsor and Windsor Downtown Alliance.

A safe gathering place

Two of the highlights, which Vance hopes to get done sooner than later, are what she calls a “refresh” of Main Street and a potential 5th Street Plaza.

Both are designed to help downtown Windsor overcome issues that make it an unfriendly place for pedestrians, at least according to the surveys residents submitted. Vance hopes to install pedestrian crosswalks, replace sidewalk surfaces and rework diagonal parking spaces in front of restaurants to encourage more outdoor dining.

Some of the changes, by comparison, may seem inconsequential, such as additional flower beds and street planters as well as more trees. But even those have a purpose, she says, as they should encourage drivers to slow down and gaze at all the scenery. Colo. 392 turns into Main Street, and cars whooshing down the road have always been an issue.

The proposed 5th Street Plaza would, much like Old Town Fort Collins, become the center of activity, a “cultural heart and soul of the entire Windsor community,” as the plan suggests. Closed off from traffic, it would include natural places for kids to play.

Vance likes to joke, but only half-heartedly, about how parents play goalie to keep their kids out of the street, where many drivers go highway speeds. The plaza would feature interactive water features, a performance stage and a range of other possibilities, including walk-up windows, outdoor dining and rooftop restaurant lounges. Vance hopes for murals, public art and ways to greet visitors. The new design would also connect downtown to Boardwalk Community Park and Windsor Lake, giving residents a clear path to walk.

These two projects spearhead the other ideas Vance proposes in the plan. Those are trickier, as many of the spots up for redevelopment, if not all, are already owned by operating businesses that she doesn’t want to kick out (not that she could anyway). And, yes, the plan includes room for apartments. That’s why Vance has met with so many people and wants residents to look at the plan and give feedback. It’s an alliance, not an authority.

Coming together

Vance’s approach has won over more than a few residents who were against the plans for downtown before she arrived. This includes Donald Stavely, a 35-year resident who lives downtown with his wife, Carmen. Both are retired. He was an engineer and she was a Realtor.

“I’m pleasantly surprised at how the DDA got in front of this issue,” Stavely says, using the old name. “I thought it would take years to repair the damage, but Michelle has done a fabulous job. If she had been there earlier, I don’t think we ever would have had this unpleasantness.”

Stavely eschewed town politics before the ballot measure regarding multi-story apartments. He, unlike some, doesn’t love controversy. He doesn’t have social media for that reason, not even Facebook, though he does like Nextdoor. The one thing he will say about the apartment issue is he felt told to, rather than listened to, about the city’s downtown plans, an attitude that led residents to put together the ballot initiative and vote against it. Stavely doesn’t agree with former Mayor Paul Rennemeyer’s attitude toward the whole thing, but he also blanches when residents on Nextdoor call Rennemeyer corrupt, saying those comments aren’t helpful.

Stavely is now doing his part in civic government, he believes, by acting as an unofficial community liaison for the WDA. It’s a volunteer position. He doesn’t just want to shout down plans he doesn’t like.

“I try to be a moderating influence,” he says.

The proposed apartments don’t bother him because they aren’t several stories high, as the other plans detailed, and they wouldn’t block the view of Windsor Lake or be such a dominating presence that they would change the character of downtown.

He still doesn’t think Windsor’s downtown needs new residents, and he disagrees with Vance on this point.

“I believe efforts should be to attract people to downtown,” Stavely says.

The projects are in the preliminary stages, meaning there’s no real cost estimate or specific plans to pay for them. But Vance believes there are plenty of redevelopment grants and other ways to help with financing.

A Windsor master plan illustration representing what a boutique hotel could look like on the 400 block of Main Street. Rendering courtesy of Town of Windsor and Windsor Downtown Alliance.

Dreams of what could be

Beyond these two projects, Vance decorates her office window with possibilities. They are also part of the master plan, but that doesn’t mean they are sure things. They include redeveloping the 500 block of Main Street with a brewery and restaurant and turning the gas station on the 400 block of Main Street into a boutique hotel. Many developments, even possibilities not listed here, have options for a story or two of condos or apartments above the downtown businesses.

These would be privately developed projects, so Vance couldn’t control them, but she’s already meeting with developers, she says, and interest has been high. She uses the Windsor Mill project as an example of what redevelopment can do: Taxes before its resurgence totaled $3,000. Last year they collected more than $77,000.

“The most valuable land,” Vance says, “is downtown.”

Illustration depicting a revamped 4th Street in downtown Loveland. Renderings courtesy of Russell + Mills Studios.

Downtown Loveland catches up

Back in 2009, the City of Loveland approved a master plan for renovating the downtown. Since then, city officials have occasionally taken a look, only to be overwhelmed by the scope of the project and put it back on the shelf.

Now there’s a sense of urgency, says Nicole Hahn, city engineer with Loveland’s public works department, and that’s good news for the downtown advocates who are practically begging for a refresh.

The city’s water line downtown is more than 100 years old and could, in theory, fail at any moment. That may sound a bit extreme—it’s not in immediate danger—but it’s also true. The concrete sidewalks are also crumbling and don’t meet current standards set by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Since the city needs to tear up the road anyway to fix the water line and sidewalks, they figure, why not make the kind of improvements that downtown has been waiting for since 2009?

And yet, the urgency goes beyond infrastructure. It’s time for the city to match the energy of the businesses that have moved in and made Loveland a fun place to play as well as work, Hahn says.

“There’s a vibrant life downtown,” Hahn says. “We’ve seen a lot of private investment. This is an opportunity for us to catch up to it.”

Illustration depicting a revamped 4th Street in downtown Loveland. Renderings courtesy of Russell + Mills Studios.

A worthwhile investment

Hahn was one of the engineers who helped transform Linden Street in Fort Collins, and she sees similarities with this project, which Loveland is calling its Heart Improvement Project (HIP Streets). The work will fix the water line and improve 4th Street—considered the heart of downtown—from Washington Avenue to Garfield Avenue. The plans include making parking spaces parallel instead of angled, creating safer areas for pedestrians and adding more places for artwork that allow it to shine.

That last point is especially important, says Sean Hawkins, executive director of the Loveland Downtown District, because it could give the city and businesses opportunities to close the road for more festivals, concerts and events. It would also help nudge Loveland into a downtown that thrives on foot traffic, as all the best ones do.

Hawkins believes the improvements could bring an additional $100 million in private investments. Hahn concurs, as she noticed an immediate interest in the Linden Street area after improvements were made there.

“Communities are competitive,” Hawkins says. “Longmont just made huge improvements. You do have a lot of options in this area, and we have been behind. A lot of places have made these improvements, and we just haven’t.”

Historically, Hawkins says, renovations to an area can spur interest in blighted properties. Usually organizations such as the DDA and the city see a five-to-one return on investment. The DDA will put $9 million into the HIP Streets project, and the city will pay for the rest, essentially covering the water line replacement.

That’s partly why this project feels important, Hawkins says, as the plan calls for 19 revamped blocks (eventually) and needs to get off on the right foot.

“We’ve gotta get this one right,” Hawkins says. “This is the project that will propel others.”

As of early April, the City of Loveland was 60 percent done with the HIP Streets design, which makes it sound like they have a long way to go. But Hahn calls the rest of that work “tweaking.” They hope to start construction this October.

Hahn says she gets asked many times a month about the project, and she calls the downtown revitalization “some of our most exciting work.”

Hawkins agrees. “We’ve waited a long time for this,” he says. “It’s about time we got started.”