Kate Conley designs affordable housing for Architects FORA, a firm she owns with two partners. There were many times she wondered if she should also be a client.

She and her husband lived in San Francisco until a couple years ago. They knew they needed to move when a broken-down home across the street from their two-bedroom rental was listed for $2.7 million. Her husband suggested Colorado, where he grew up, and after a long search, they found a small single-family home in Fort Collins. It was barely affordable, even for a dual-income household with an architect’s salary.

“It’s the great issue facing our generation,” says Conley, who calls herself and her business partners “elder millennials.” “None of us can afford homes. I’m almost 40 and just now have my first home.”

Conley fights for affordable housing in her spare time, too, as a member of Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY), a national organization with a Fort Collins chapter that formed last year to defend the city’s new land use code.

A petition convinced the council to overturn the code, so YIMBY’s efforts failed, at least for now. The new code would have allowed for, among other things, smaller homes and denser neighborhoods, much of which would’ve been designed to make housing more affordable in Fort Collins and Northern Colorado in general. It’s the same idea Gov. Jared Polis tried to get approved by the Colorado legislature in May with a bill that would force local municipalities to allow denser developments. That bill was killed on the session’s last day.

Fort Collins updated the code last October, but after a petition with more than 5,000 signatures was filed by a group called Preserve Fort Collins, the council repealed it. The council’s only other option was to bring the land use code to voters in a special election that would cost tens of thousands of dollars.

The idea of creating denser neighborhoods follows a boom in multi-family housing construction in Northern Colorado, another market trend that cities encouraged to offer a wider range of housing options and help dent the affordable housing crisis. The situation is so bad that Habitat for Humanity, a longtime stalwart for affordable housing, is changing the way they address it.

Not everyone is happy about the way cities are approaching the crisis. Preserve Fort Collins claims that denser neighborhoods would turn Fort Collins into another Denver.

What’s clear is that housing, especially the single-family home, continues to be unaffordable for a growing number of people nonprofits call “the missing middle.” These are people who can’t afford to buy a home, or even a townhome, yet they make too much to qualify for most social programs. Buying a single-family home, as Conley’s own situation demonstrates, may be more of a pipe dream than an American one for many Northern Colorado residents. Even experts agree with that.

“It’s getting to a point where a single-family detached unit is so difficult to build and make affordable,” says Brett Limbaugh, Loveland’s Development Services director.

Breaking ground on the Hope Springs development in Greeley. Photo by Robert McCleave, RAM Drone Photography.

A new normal

Kristin Candella prefers to talk about the growing number of working, middle-class people who never would have had to apply to her organization even 10 years ago.

“These are real people who say, ‘I’ve moved 14 times in the last eight years and now I live in a trailer or a small place owned by my church,’” says Candella, executive director of Fort Collins Habitat for Humanity.

The numbers are indeed striking. A recent evaluation done by Habitat and the City of Fort Collins found the city was short on so-called “missing-middle” housing by 35 percent, and affordable housing, which has a lower income tier, was also lacking by 35 percent. Those numbers, according to Candella, mean a third of Fort Collins is paying at least half their income for housing. That’s a cost burden that means many can’t afford other necessities, like health insurance, medical care and sometimes even groceries.

The data is stark enough that Habitats in both Fort Collins and Greeley are rethinking their models. The old model only helps one person at a time. These aren’t people waiting for handouts: The Habitat office in Greeley recently helped employees from Greeley-Evans School District 6, says Cheri Witt-Brown, executive director of the Greeley-Weld Habitat for Humanity.

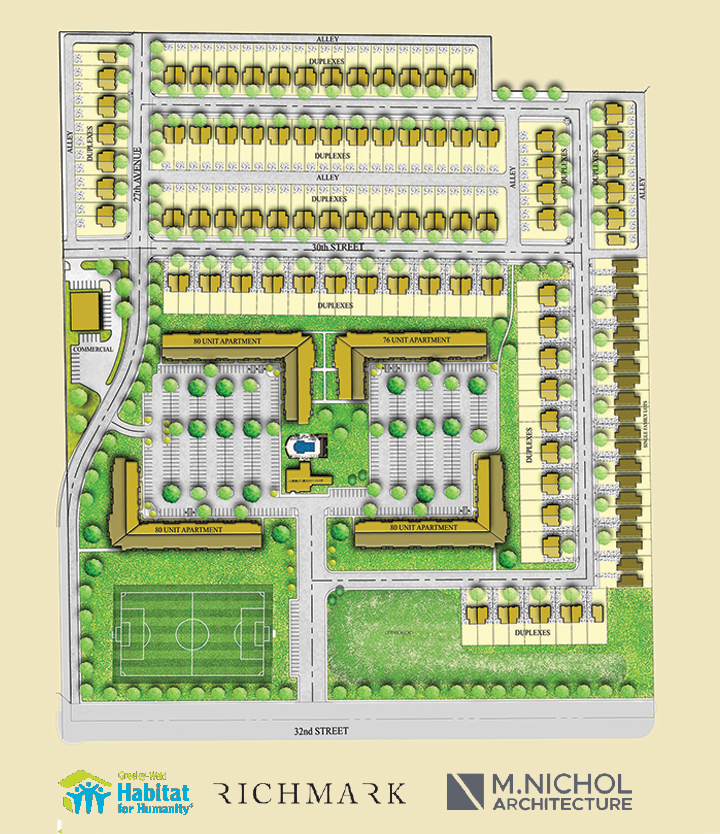

Greeley’s Habitat office recently built 68 townhomes and cottages as well as 27 paired and single-family homes in a partnership with The Commonwealth Companies, a nationwide affordable housing developer. An even bigger project, called Hope Springs, is underway near the Greeley Mall. The neighborhood will feature a soccer field, daycare center and open space, all in a walkable distance from Wal-Mart. It will contain more than 150 duplex units, 22 single-family homes and 300 apartments built by Richmark, the developer that donated the $8 million in land to Habitat. Richmark will own the apartments, and some may be market value.

“That’s healthier anyway,” Witt-Brown says of the mixed income neighborhood. “Why are we segregating people according to income?”

The Fort Collins Habitat is tackling a similar project in partnership with Hartford Homes, which donated the land to build 110 condos at the intersection of Timberline Road and Vine Drive. Hartford will build 80 of them, and Habitat will build the rest.

The projects will take time. Hope Springs won’t be complete for at least five years, but when it’s built out, more than 600 families in Northern Colorado will have access to affordable housing, Witt-Brown says. Habitat couldn’t have helped that many people eight years ago, when Witt-Brown realized Habitat’s model was outdated and began thinking about other ways to help cut into her waitlists.

“We’ve developed a sustainable model that can be replicated anywhere,” she says.

Greeley’s willingness to budge on lot size requirements was a key to the success, and she hopes other governments take note.

Hope Springs rendering. Courtesy of Greeley-Weld Habitat for Humanity.

The apartment boom

In a busy year, Greeley might issue building permits for 1,000 apartment units, says Brian McBroom, the city’s community development director. In 2022, 1,500 units were permitted, and that isn’t the only significant number. Currently, there are 10,000 units either with building permits or that are somewhere in the permit approval pipeline, meaning that in the next year, if all those developers wanted to, Greeley could see 10,000 new units spring up.

That won’t happen because developers don’t want to flood the market, but it shows how increasing prices for single-family homes have affected it, McBroom says.

There are many other reasons cities want multi-family housing besides the fact that it adds to the affordable stock.

“You have a balanced, diverse community that way,” McBroom says. “Safe, affordable housing is certainly a priority, and apartments fill that need.”

But apartments alone are no guarantee that housing will be affordable. There’s still a big gap: Most of the apartments available are so-called market rate units, which may or may not be affordable, depending on who you are.

After years of Greeley planners pining for more multi-family units, Juliana Kitten, Greeley’s assistant city manager, wonders if the city will soon have too many.

“We need to see avenues for homeownership too,” Kitten says. “You have to have options. [More apartments] will help, but the concern I have about it is we always need to have as much choice as possible.”

Kitten hopes to help by hiring a housing director. Most of that person’s job will be to find affordable housing solutions.

Loveland revamped its housing code last summer, Limbaugh says, by including incentives for affordable housing, expanding housing opportunities in the city’s medium density residential zone, creating standards for smaller homes and shrinking lot sizes for duplexes and townhomes. Loveland also did a housing needs assessment a couple years ago and found that it was 4,000 units below what the city needs. Supply and demand is the surest way for prices to go up.

Limbaugh is excited about the shrinking lot sizes for single-family homes, something that could encourage developers to build more of them. That would help meet the demand and, in theory, make them more affordable, albeit on a smaller scale.

“The 7,000-square-foot lot is no longer affordable,” he says.

He also says Loveland’s planning staff will prioritize projects that address affordable housing, even if it means setting aside more expensive projects to do so.

“We will get to market-rate housing,” Limbaugh says, “but affordable housing is on top of our priority list.”

Conflict over codes

Larger lot size requirements, Candella says, were created decades ago and are considered relics by affordable housing directors. Other requirements hinder affordability as well, she says, including parking space requirements, height restrictions and laws that limit the number of people who can live in one dwelling. Each of these factors take up valuable space.

“Land use decreases affordability,” Candella says. “It needs to change nationwide.”

There are many who believe Polis’ ideas and the Fort Collins land use code goes too far. Polis’ plan, after all, was voted down by a group of Republicans and some Democrats. Ross Cunniff, who filed the petition and leads Preserve Fort Collins, has the usual concerns about traffic that many homeowners have about developments near their neighborhoods. Cunniff’s group also argues that the land use code didn’t guarantee any affordable housing, as there were zero mandates for it. Cunniff says developers would respond to the denser housing by building high-end townhomes and condos.

“If you want to provide housing for the people who are having trouble affording it, you should provide intentional housing, like section 8 vouchers,” he says. “I don’t think anyone would disagree with those kinds of actions. Our group doesn’t.”

Cunniff also says the land use code would turn Fort Collins into an urban metropolis, stating that Colorado “already has a Denver, and we don’t need another one.” He says there are still places in eastern Fort Collins that are undeveloped that could feature denser housing developments without changing the density of established neighborhoods, therefore preserving their character.

Cunniff, who works in high-tech software, says many high-wage earners want to move to Fort Collins. The city seems to attract those workers and the companies that employ them, he says, and those wage earners desire and can afford single-family homes.

This point rankles Conley and others in support of the code because housing has gotten so expensive that it’s affecting even long-time residents of Fort Collins who make up the working class. Those are some of the people Conley is trying to serve.

“People who work here should be able to live here,” Conley says.

Fort Collins hasn’t given up on finding solutions to affordable housing. As of press time, the council planned to meet in mid-January to discuss options after they repealed their first try. Members from both Cunniff’s and Conley’s groups planned to be there. Conley also hopes attitudes can change statewide.

“We’re keeping one eye toward statewide legislation that may inform the outcome of the land use discussions in Fort Collins,” she says.