Photos by Jordan Secher

Matt Rivette was worried about sounding redundant when he approached the Greeley City Council in early September 2022 about the homeless downtown. He’d been there earlier that year to express his concerns.

“Something has changed,” Rivette, who owns property downtown, told the council. “A tenant had a knife pulled on them last week.”

What followed was perhaps the most emotionally charged meeting of the year, as business owners took to the stand to talk to the council the way a frustrated spouse may talk to their partner. They rehashed some complaints, such as having to wash feces off their buildings, but they also expressed new ones, including being afraid for their customers and themselves. Some had weapons pulled on them, too. Others had been harassed. Ryan Gentry, who lives in downtown Greeley and owns several taverns, said he and his wife had been startled awake more than a dozen times that summer by someone screaming in the middle of the night.

The mural is a result of a group effort between Front Range Community College and Murphy Center guests, circa 2014-2015.

The problems are a sore spot for downtown owners like Gentry, who for years had battled the perception that the area was unsafe. In the early-to-mid 2000s, west Greeley residents refused to go downtown, saying it was riddled with gang members.

Years of hard work had changed that. They’d supported other businesses that shyly opened stores, such as The Nerd Store, and cheered when fun breweries, like Wiley Roots and WeldWerks, and distilleries, like Syntax and 477, found success. When Friday Fest, with free live music and the chance to drink outside, became popular and drew thousands to Greeley, downtown became hip.

“Let’s not forget what we’ve done in the last 15 years,” Gentry says.

The owners were indeed angry—Gentry called them “vagrants”—and yet, they were also contrite. They acknowledged how hard it must be to be homeless. They knew the problem was a difficult one. These were people, not feral cats, they said. Many of the owners left the stand in tears after speaking.

Juliana Kitten watched the meeting online with her own set of mixed emotions. Kitten had just been hired as Greeley’s new assistant city manager, mainly because of her two decades of experience with the homeless population as a social worker and administrator. It would be her focus, if not her job, to do something about it.

Anthony Enfield, facilities coordinator at the Murphy Center for Hope, shares his personal story

of homelessness.

The meeting wasn’t a turning point (Kitten had already been hired to work on the issue), but it demonstrated how the homeless became the biggest social service concern in Northern Colorado. In the last few years, especially after COVID-19, our area’s largest cities, along with United Way and dozens of agencies, have devoted millions of dollars and hundreds of hours in a concerted effort to clean up encampments, build shelters and ease the concerns of residents. COVID-19, in fact, is the only other issue in recent memory to receive this much collaboration and concern.

Cities have learned in the last decade that hoping nonprofits can tackle the homeless issue alone doesn’t work, and there are other reasons for the huge effort. Lack of affordable housing is one of the key reasons why homeless populations grow in cities, and Northern Colorado, especially Larimer County, is on the precipice of pushing a significant portion of our population out to the curb based on our median income and the cost of both renting a space or owning a home.

Kitten, however, was not afraid nor angry while watching the meeting. She calls the issue, along with housing in general, “my life’s work since 2000.” She’s excited about Greeley, and Northern Colorado as a whole, and sees this complex issue as a real chance to do something meaningful. The fact that the downtown owners didn’t want to blow the homeless off their porches with fire hoses encouraged her.

“Most were very respectful,” Kitten said of the owners. “It can get very ugly. My job as assistant city manager is to do the best job I can for every single person. Here’s the bottom line: Having a person homeless in front of your business is bad for everyone.”

There is, in other words, an opportunity to turn it around, Kitten says. Northern Colorado can establish a system that prevents most people from becoming homeless, and for those that do, helps to ensure they don’t become chronically homeless. Those are the ones on the streets most of their lives who are more likely to cause the problems that led downtown owners to tears. The goal, in fact, is to assist them so they aren’t homeless for longer than a month. Kitten said Greeley, and, by extension, the rest of Northern Colorado, can be the model for the rest of the country.

“I know that we can do it,” Kitten says. “It will take a few years, but it is absolutely doable.”

As many problems as people

Daniel Brisson is a professor at the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work who studies communities, poverty and affordable housing. He’s also part of the Center for Housing and Homelessness Research, which helped Loveland study its own problem before the city took actions such as opening up a night shelter in April. Surely devoting his own life’s work to this issue, and all those accolades, means he knows the root cause of homelessness, right?

“The quote I’ve used for many years came from someone who has experienced it,” Brisson says. “There’s as many different causes as the people experiencing homelessness.”

Many interviewed for this story, from experts like Brisson to social workers to nonprofit directors and city staff, said homelessness gets so much attention as a social issue because it’s all of our social issues. It’s mental health struggles, poverty, affordable housing, isolation, transportation, unemployment, fractured families and relationships (including domestic violence, which plays a huge role), substance abuse and limited resources to deal with all those problems. There’s also bad luck.

Brisson said that last point, just sheer bad luck, can play a key role. Most people have the gumption to tackle one or even a handful of those problems—you might be dealing with one right now. But what happens when there’s what Brisson calls a perfect storm? The Center for Housing and Homelessness Research asked those experiencing homelessness in Englewood and found a few common factors that matched the ones listed above. They lost their homes when those variables crashed together.

“You’re down on your luck in a relationship, and then two or three other things happen, like you lose your job, and you might already be struggling with your mental health,” he says.

This is why Kelli Pryor calls homelessness a symptom. Pryor is the director of the Northern Colorado Continuum of Care for United Way of Weld County. She moved behind a desk a year ago when she became director of the continuum. She was on the front lines for years before that.

“[Homelessness] is the result of a lot of other things,” Pryor says. “It’s everything. That’s partly why I say it takes a community.”

She leads that community, at least in part. Most of her job is to coordinate services among the dozens of agencies in Weld and Larimer counties so precious resources, such as shelter space, food and stable housing, aren’t duplicated or unused. Those efforts, and the many others Kitten referred to, will be covered in part two of this series.

If you somehow solved domestic violence, for instance, you’d likely cut the homeless population by 25 percent, as that’s the number of people who find themselves homeless because they are fleeing an abusive partner, Pryor says. There are other family issues that can lead to homelessness: family members die, get ill or fight, and when they do, others wind up without a place to go.

Families and friends are safety nets, Pryor says, and without them, even those who have never had to spend a night on a couch can be out in the cold. Our social system also doesn’t have ways of helping those in downward spirals.

“[The system] is not meant to catch people before they become homeless,” she says.

Many programs won’t, or can’t, help those struggling to pay rent until they’re facing an eviction notice, she says.

“They have a lot of barriers,” Pryor said of those on the edge of homelessness. “Many we don’t even know about.”

That’s partly because most homeless people don’t report themselves as such, Pryor says. The vast majority do have networks and aren’t homeless for more than a few days.

The official number of those homeless and in the system—nearly 900 in Weld and Larimer Counties as of April 2023 have had their housing needs assessed by a service provider—is always considered underreported.

And yet, eventually, those struggling to stay afloat will experience what agencies call episodic homelessness. That’s the bulk of the homeless population: People who occasionally don’t have a place to live but can’t find the help they need to keep them housed.

COVID-19 was a boon for the homeless issue, and that’s not just because the federal government sent millions of dollars to agencies to help. People began to recognize that most people like them can run into problems caused by unforeseen forces.

“People now are more willing to acknowledge it’s not just the drug addict on the street,” Pryor says.

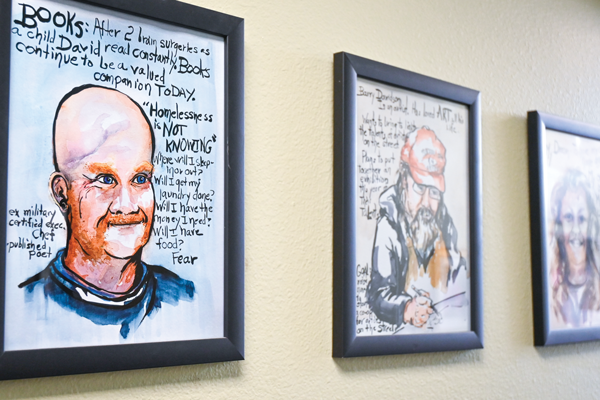

Paintings depicting past guests at the Murphy Center.

The high cost of living

As Brisson and others point out, more than a few people might even be able to tackle all those problems above if average rents and mortgages were reasonable by most wage standards.

“If you had units for $450 a month,” he says, “do you think we’d see people sleeping in parks? Housing can be so unattainable. It’s so damn expensive, and that message is understood by just about everybody.”

As the cost of housing stays high, the margin of error to cover our butts when life gets hard shrinks to nothing. It makes it hard to recover when just one thing goes wrong, like a temporary job loss.

In fact, homeless populations tend to rise when the cost of housing is more than 32 percent of the median income in any area, says Jared Olson, a senior population epidemiologist with the Larimer County Department of Health and Environment.

Larimer County is at 29 percent.

It may seem strange for a health department to study the cost of housing, but housing, Olson says, is health. More than 60 percent of those who live with housing instability report poor mental health, he says, and that doesn’t address the food insecurity and overall security problems that come without a place to stay. You’re exposed to the weather and are more likely to get sick without a safe space.

Being homeless, unsurprisingly, is bad for your health, and when you spend more of your income on housing, you’re more likely to go homeless.

“It makes it harder to put that pie of your budget together,” Olson says. “Food costs have increased, transportation is high and the pressure of housing continues to grow.”

It’s not the only factor of how well we thrive, of course, but there is enough of a correlation that he can say, with confidence, that it matters.

Housing is market-driven, but there are ways a city can help, he says. Denser apartments, even those with a shared bathroom or kitchen, can offer more units without reverting back to project-style concrete jungles in large urban cities. Even requiring an overabundance of parking spaces can drive up housing because of the valuable space smothered in asphalt.

Gov. Jared Polis attempted to address this with a land-use reform bill that would allow more townhomes and multiplexes in areas restricted to single-family housing. As of press time, the bill was inching its way through a House committee.

Cities, however, were resistant to this, as the Colorado Municipal League, a lobbying group that represents cities and towns, fought it, along with several mayors who blasted the bill and stated they were already trying to address affordable housing themselves.

The Greeley City Council approved a resolution opposing the bill. Fort Collins’ council updated its Land Use Code in November 2022 following Polis’ intent, but in January, it rescinded the code after residents working under the name “Preserve Fort Collins” filed a petition against the changes. The group stated that allowing more dense housing types would diminish the city’s quality. Fort Collins hopes to bring another land use change in August, this time with extensive citizen input.

Indeed, residents of single-family neighborhoods have long said they support affordable housing but generally oppose anything, including apartment complexes or even duplexes built near their neighborhoods that could, in theory, help the cause, Olson says.

Kitten says she was hired by the City of Greeley to address housing of all types, not just the homeless. She says Greeley needs homes of all types, large and small, but also acknowledges the burden that housing prices can place on those with lower incomes.

“Housing prices are just nuts,” Kitten says. “But I also think this is true across the country.”

Anger can help

No other social issue creates a wider spectrum of anger and empathy than the homeless, and to be blunt, they benefit from both.

“There are people who don’t like to see homeless people outside when they go to the store,” Olson says. “But this can be a good thing.”

Rather than ignoring the homeless, cities have bulked up their own efforts and assisted agencies in trying to solve the issue because residents protest, loudly and publicly, much like they did in Greeley that September evening at a council meeting. But those same cities and agencies—even those same residents—also feel for those sleeping on park benches, especially when winter arrives.

After all, Loveland built its shelter because it outlawed encampments after residents complained about them. Fort Collins’ extensive network of services is owed in part to the outbreak of encampments in visible, popular places such as City Park.

They’re one of us

COVID-19 helped us relate to those struggling with hard times, and now there’s also a greater understanding of how someone becomes homeless. We know they aren’t hobos riding trains to campfires and cooked beans.

“We’ve gotten [a better] understanding of the homeless now,” Pryor says. “We used to think they weren’t our community members. They were just others. But they are.”

Anthony Enfield was 37 in 2017 when he moved to Colorado to be with a woman. He moved in with her and had trouble finding work. When they broke up, he had a job but nowhere to go, and he couldn’t afford the high rent in Fort Collins.

He was homeless for a year. He would rest at night by the river in a sleeping bag and go to work during the day. The pandemic, he said, actually turned his life around. Someone told him to go to the Murphy Center for Hope, a resource center for the homeless in Fort Collins, which connected him with agencies.

He found a steady job collecting trash that paid well, and Volunteers of America found him an apartment and covered his first three months’ rent. When the three months were up, he didn’t need help anymore, and the Murphy Center saw how hard he worked and offered him an internship.

He’s since worked there three years and been promoted three times. He’s now the facilities coordinator. It’s a lot of chores—he empties trash, changes the paper towels in the bathroom and picks up trash on the grounds—but he also gets breakfast together for those who come in from a cold night and does their laundry, both jobs he finds fulfilling because he used to experience the same things.

He’s now dating a high school teacher and pays $1,800 in rent, which he doesn’t love, but he’s also happy he can.

“She told me she doesn’t want a project,” Enfield said of his girlfriend. “I told her I don’t want to be one.”

He’ll never forget what it was like to be in the same situation many of the people who surround him now are in. He rarely loafs around the Murphy Center—he averages nearly 40,000 steps a day, though part of that comes from walking his dogs at night. If he does pause, it’s to do his favorite part of the job: talking to people who come in.

“When they are having a bad day, they will tell me what’s wrong,” Enfield says. “I tell them to make their appointments and do the right things and things can change. Many want it right now, but I tell them it will happen.”

When he walked outside on a cloudy day in May, he noticed one of his friends sitting outside in the parking lot. Her eyes lit up when she saw him emptying the trash.

“Have a good day, Mr. Anthony!” she yelled to him.

He would, he told her. He definitely would.