NOCO meditation experts share their secrets for finding your center

Our lives are busy; it can often feel impossible to slow down. Work, errands and chores are one thing, but even the fun stuff can lead to jam-packed schedules with little room for peace and quiet.

Our lives are busy; it can often feel impossible to slow down. Work, errands and chores are one thing, but even the fun stuff can lead to jam-packed schedules with little room for peace and quiet.

That begs the question of how to slow down—some of us prefer quiet mornings with a cup of tea while others end the day with a Vinyasa flow. Journaling helps us get our thoughts out. There are even apps to promote calm. But what if we could go inward all on our own, without the help of prompts, classes and apps?

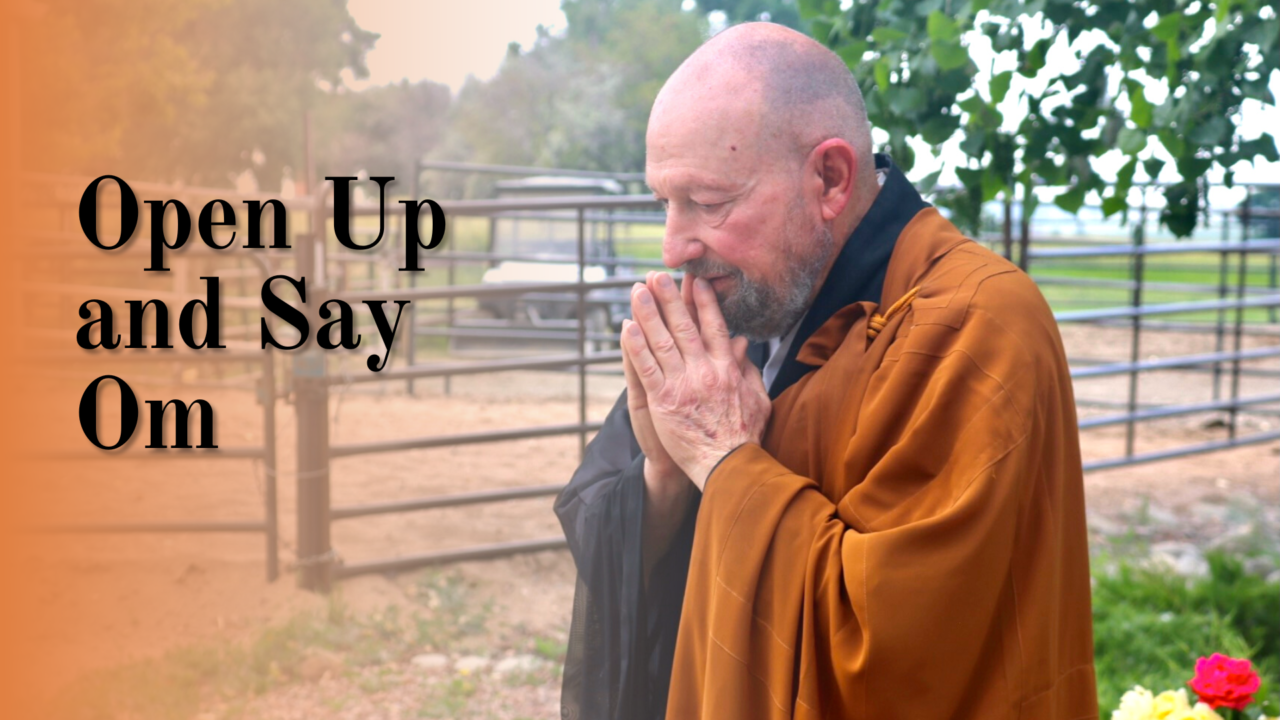

Anyone can learn to meditate, and everyone’s reason for meditating is valid, says Gerry Shishin Wick, Zen Master and president of the Great Mountain Zen Center in Berthoud.

“Some people just want to be more at peace, to feel calmer and [gain] equanimity and to not get so frazzled by the ups and downs of life,” he says. “Or maybe they’re feeling dissatisfied with the direction their life is moving, or they want to explore the deeper meaning of their existence.”

According to Wick, meditation’s focus isn’t to examine the content of our thoughts, but to observe their nature—how they arise, how they persist, how they pass through—without entertaining them. The trick is to do so without trying to push them away, but to simply allow them to come and go.

To stay focused, Wick suggests counting breaths up to 10 and then starting back at one, and if a thought is too important to ignore, jot it down on a piece of paper and forget about it until the end of the meditation. He says it’s normal to feel frustrated when we latch onto our thoughts; we just need to come back to our center and try again.

Keeping the mind from wandering isn’t the only challenging thing about meditation. The posture itself can be difficult to maintain at first, as it can feel unnatural to sit on the ground, legs crossed, with the back and neck straight, not slouched. However, Wick says this posture allows us to hold our center of balance in the lower abdomen, or “hara,” keeping our energy strong and steady. It just takes time to adjust to it.

Many people who are new to meditation experience some aches and pains at first, says Sarada Erickson, co-founder of Om Ananda Yoga in Fort Collins. Whether it’s the lower back, the hips or the knees, she says warming up with yoga can help.

“The original purpose of asana, or yoga poses, was to prepare for meditation by physically getting the body comfortable for sitting while relaxing the nervous system,” she says. “Asana is like a bridge between daily activities and deep meditation, where you’re moving, breathing and starting to feel inside your own being rather than being caught up in external distractions.”

“The original purpose of asana, or yoga poses, was to prepare for meditation by physically getting the body comfortable for sitting while relaxing the nervous system,” she says. “Asana is like a bridge between daily activities and deep meditation, where you’re moving, breathing and starting to feel inside your own being rather than being caught up in external distractions.”

Erickson calls the transition to sitting meditation “finding your seat.” The hips should be elevated on a cushion with the legs crossed and the knees lowered, allowing the hips to open and the back to strengthen. Be patient with your body by sitting for shorter amounts of time until the aches and pains subside—technically, it is possible to meditate lying down, but that can be an invitation to sleep.

The way we set up our space can also make or break our concentration. Wick says it’s important to have a clean, quiet place to sit in every day, whether that be at a meditation center, a yoga studio or at home. The space should be free of all other activities, especially unfinished work and items on the to-do list.

It’s also easier to find the motivation to meditate when there is a designated time and place to do it. Some people prefer to meditate first thing in the morning, before tasks come flooding in, and others like to wind down at the end of the day with a moment of mindfulness. Either way works, as long as it is part of a regular routine.

“You have to prepare yourself mentally and physically in order to have a good experience,” says Erickson. “Incorporating other small rituals into the routine, like lighting a candle or putting on a meditation shawl, can also signal to your mind that it’s time to transition into that meditative space.”

Erickson and Wick also recommend meditating in a group, sometimes referred to as a “sangha,” because there is a sense of group accountability rather than relying only on self-discipline. Just feeling the intention of others meditating in the same room can provide the support and structure needed to stay focused, resulting in a longer and more productive meditation.

Retreats take the benefits of group meditation to a whole new level by adding other practices like yoga and tai chi to help release tension in the body between meditations. Erickson says spending time with people who are doing something you want to do can help you get better at it because you do it more frequently—as long as you don’t give up when you get home.

“Getting to know others in the yoga and meditation community can be really inspiring, even if you’re just reading their books or listening to guided meditations,” says Erickson. “When we realize how many of us are suffering, it can help us feel connected to each other and our greater purpose. We’re all looking for happiness, peace and comfort—it’s a human commonality.”