Armed with an impending marriage and a new promotion to assistant manager at Chick Fil A, Jamie Edens prepared to shop for her first home—a goal, she knew, that many thought was beyond her age of 22. But she was determined: The job paid better than many thought, and Jordan, her fiancé, was on track to earn the same promotion.

She even had what she thought was a responsible and realistic limit of $250,000. But as she began to tour Greeley, the reality of Northern Colorado’s real estate market began to sting.

She and Jordan did find a few homes for under $250,000, but they were old—one was built in 1910—and therefore full of potential problems that couldn’t be swept away with a gift certificate to Home Depot. You can’t, she said wisely, remodel a foundation. Discouraged but undaunted, she looked at condos in the Pinnacle development in southwest Greeley and began to salve her disappointment with the positives.

She wouldn’t have to take care of a lawn or, really, the home at all, save for some improvements such as tearing out the carpet and doing some indoor painting. The condo fit her budget, and it was built in 2006, or nearly 100 years after 1910. Plus, they were young. They wanted five years to themselves before kids would demand a larger place. Jordan did indeed get the promotion, and maybe when the kids came, they would use the condo as rent income. Jamie purchased the place in August and moved in with Jordan last fall.

“I did want a house, but honestly, I do think this is better overall for our lifestyle,” Edens says, who got married in September and is busy making those modifications to the condo. “We want five years to enjoy things, and the condo will really help with that. It was a good choice for us.”

Several trends now color Northern Colorado’s real estate market, and all of them are either being shaped or sparked by affordability. That’s been an issue for years, two decades, really, as first Denver residents in the late ’90s, and then yet another surge from California, have discovered that cities such as Fort Collins, Loveland and Greeley are great places to live. But affordability is affecting the Northern Colorado market in many different ways now, and all the trends affect all three cities the same, even if there are minor differences between the trio.

The most obvious, of course, is the thousands of residents such as the Edens who have good jobs and good income who can’t afford a traditional single-family home. Those people now buy townhomes, condos or continue to rent apartments. There are upsides to that, but it does mean the so-called American Dream will have to wait a few years for more and more Northern Colorado residents.

But affordability continues to affect the housing market in ways that surprise real estate professionals.

Home prices are so high compared to wage growth that programs designed to help first-time home buyers, such as low- or no-interest loans for a down payment, are essentially dormant. This has prompted local governments to not only take a look themselves but form a regional alliance to attempt to find solutions.

High prices have also slowed construction on single family homes while builders prefer to construct apartments, townhomes, duplexes and condos to meet the increasing demand of those who can’t afford a house, and developers are piecing together mixed-use centers with multi-family buildings and single-family homes and even sprinkling in some retail and office space, a trend that’s hit Greeley after a decade in Fort Collins and Loveland.

The high home prices have even affected home prices themselves, as buyers balked at buying what they began to believe were overpriced homes. That helped slow things to what real estate agents are calling a normal market after years of annual double-digit growth. The demand just isn’t there as much as it once was because there are a lot of workers who know they can’t put 50 percent of their income into a place to live.

“Buyers are just saying no,” says Matthew Gardener, chief economist for Windermere Real Estate in Fort Collins, during the company’s annual forecast of the market in Northern Colorado, held in January. “I’m not worried about it. A well-priced home will still trade quickly. But we haven’t seen a normal housing market here in a long time.”

Meet the new normal, same as the old normal

If you want to know what “normal” is, well, maybe it’s best to start with what it isn’t. Less than three years ago, an incredulous Eric Thompson, president of Windermere Northern Colorado, snapped a photo of 14 formal offers lined up on a long table for a Fort Collins home that had been on the market for 24 hours. Prospective buyers were writing tear-jerking letters begging homeowners to let them pay $20,000 more than the listing price. One of those letters was from a dog.

“That’s not normal,” Thompson says in a dry understatement.

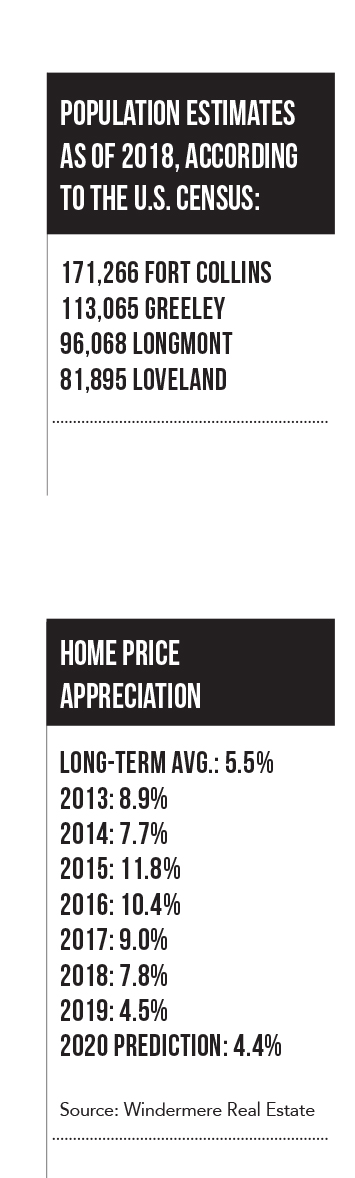

That abnormal demand, as you may expect, produced prices that went up significantly year over year from 2013 to 2018. In 2019, in Fort Collins, home prices went up by a much more modest 4.5 percent. Thompson projects they will rise by 4.4 percent this year, steady and solid but unremarkable growth.

“That’s normal,” Thompson says. “But we’ve been running up those flights of stairs for so long that normal now feels abnormal.”

The Greeley/Evans area still appears to be booming a bit more than Fort Collins and Loveland, perhaps because home prices there had more to gain, says Chalice Springfield, president of Sears Real Estate in Greeley.

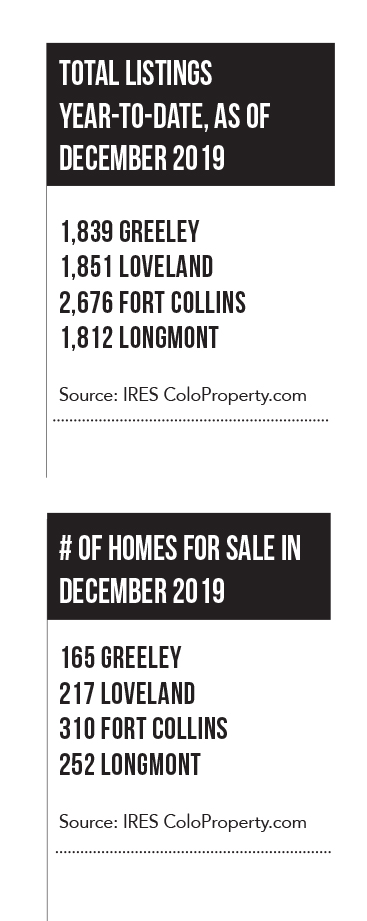

Springfield prefers to look at median home price more than average, and at the end of 2018, the median price increased by 11 percent in Greeley/Evans and nearly 7 percent in Fort Collins. Loveland even lost a bit that year at -3.9 percent. Near the end of 2019, Fort Collins’ median home price was $428,000, up nearly 3 percent, and Loveland’s was $375,000, up 4.2 percent, while Greeley was at $320,000, up more than 4.5 percent.

Those double-digit increases were nice for real estate agents on commission, but Springfield still sees the calming market as a positive thing for Northern Colorado.

“If you keep having those double-digit increases, we become Southern California,” she says.

There’s nothing wrong with Disneyland, of course, but buying a home out there is next to impossible for the middle class, Springfield says. It would still be nice to think of Northern Colorado as a place that supports the American Dream instead of Disney.

Reality, not a Recession

Easing home prices may stoke the fears of a recession, especially given how bad the last one was (many called it the Great Recession in a nod to the time period essentially being a modern Depression), but Gardener, Springfield and others don’t seem to be too worried about that, with the caveat that it’s in their best interest to say so. For one, housing prices are easing up, not falling, and as a result, homes remain a good investment.

“You can’t sell in a year and make $30,000 anymore,” Springfield says. “But there’s still a lot of equity for homeowners now.”

Northern Colorado especially seems immune to a recession, Springfield says, given its continued population boom and job growth. Unemployment remained at 2.2 percent for Northern Colorado, even under the nation’s terrific rate. Gardener presented those numbers with a few offhand “are you kidding me folks?”

The economy is due for a recession, but it won’t be like the Great Recession that happened 10 years ago, Gardener says, and if one occurs, it will likely come in 2021 at the earliest. Besides, he says, recessions do not always cause home prices to drop.

The housing bubble is what caused the last recession, he says, which is why there was such a drop in home prices. Gardener prides himself on being an economist, not a cheerleader, and yet he couldn’t find many signs that there’s another housing bubble waiting to burst, given the bulletproof unemployment rate, steady housing growth and responsible lending since the Great Recession.

“I’m trying to find something bad in your region, guys, and it’s just kind of hard,” he said during the forecast.

Choices, not cheap housing, make for a good community

It’s not Greeley’s job, or any city’s in Northern Colorado, to provide affordable single-family homes for everyone. But Brad Mueller, director of community development for the City of Greeley, wants his city to offer choices. A community that offers all low-income housing wouldn’t be a desirable one for some, if not most, of the working population, but a community with only high-priced homes wouldn’t be anything more than a bougie bedroom community.

“We want executive, attainable and workforce housing,” Mueller says. “We want people to be able to meet their lifestyle needs.”

That’s why he admits he’s excited to see Greeley embrace Northern Colorado’s trend to offer more than suburban, single-family housing developments. Developments that were historically two-thirds single-family homes in the early 2000s now offer more multi-family housing, he says.

“That will be permanent,” he says of Greeley. “It’s consistent with what we saw a decade earlier in Fort Collins, Longmont and Loveland.”

High home prices are a big reason for that, he says, with the market simply reacting to the demand. But there are changing lifestyles as well. Even newer single-family homes have smaller yards, with more emphasis on common neighborhood areas such as pocket parks.

“Not everyone wants to have the typical 3,000 square-foot house,” Mueller says.

That includes seniors and baby boomers and millennials, perhaps the only thing those groups have in common. Seniors are weary of maintaining yards and homes, Gardener says, and millennials simply don’t want to be their parents.

“Millennials want 1,200-square-foot homes with dog showers,” he says to laughter before pausing. “I’m not joking. They are all about their pets, and they don’t want stuff. They want experiences.”

Smaller developers are still focused on single-family homes, enough so that they are still the predominant way to buy a residence, says Bob Paulsen, planning manager for the City of Loveland. But the larger projects now almost always have some kind of multi-family housing and usually offer several choices in those realms in addition to some commercial development. Many younger buyers, saddled with college loans or afraid of adding new debt, don’t want big bills.

“They really want to purchase something that won’t give them huge mortgages,” Paulsen says. “And the ability of those younger people to buy homes is really shrinking. When the median home price is approaching $400,000, and you need 20 percent down, you have to have a lot of money to bring to the table.”

Predictably, the rising demand for something other than single-family homes has put pressure on the prices of residences that do offer something different.

“It’s even difficult to find affordable condos for less than $200,000,” says Cheri DeWitt, a broker with RE/MAX

Alliance in Greeley. “Even when they tend to be one of those last-resort, cheaper, less-expensive ways to go. Even finding a patio home is difficult.”

Plenty of people but nothing to purchase

Last year, all year, the City of Fort Collins did one homebuyer assistance loan.

“The current inventory is out of reach for most buyers who would qualify for our program,” says Beth Sowder, head of the Social Sustainability department for Fort Collins.

High housing prices have essentially shuttered the program. Sowder now has a couple numbers for you to consider: In 2012 in Fort Collins, the average housing price was around $215,000, and the program could help a household of two who earned $44,000 to purchase a home. Now the average home price sits at $385,000 in 2019. In those seven years, income went up 12 percent. Housing went up 87 percent. Homes cost a lot more, and wages haven’t caught up (and most likely won’t).

“I can’t get down payment assistant deployed,” Sowder says. “The home prices we used to be able to get have all left the market. It’s really difficult.”

That means the program has to start asking itself tough questions. Does it want to support putting residents on working-class salaries into higher housing debt? Isn’t that what happened with the housing bubble, when far too many clients couldn’t afford to make regular payments?

“The people I helped five years ago have sold their house and got the equity and moved up,” Sowder says. “That’s wonderful, but now that house is off the market for us.”

Sowder says these problems aren’t just for lower-income families living week-to-week in motels. Edens, the Greeley resident in a condo, is a terrific example of what she calls “The Missing Middle,” the people with good jobs who still struggle to buy a home.

“We are really seeing that now across Northern Colorado,” she says, “and the middle is growing. Really, how many can afford the median sales price anymore?”

Even if home prices continue to stabilize and grow by a healthy 4 percent every year, those prices are already discouraging to many homebuyers. There are signs, too, that prices could rise sharply again, Gardener says.

It’s expensive to build homes because the costs are increasing. Homes need increasingly sparse resources, such as water and land, that can’t be manufactured like lumber, and labor and regulations are always expensive. People, meanwhile, continue to move here and will want a place to live. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren says inventory is a huge problem nationwide and the real reason why home prices are high.

“Build more, please. But I don’t see it happening,” Gardener says. “Affordability will really be a problem as a result.”

Struggling cities

When home prices rise beyond range of the majority of homebuyers, cities struggle as much as its residents, says Mueller.

Greeley is in as much danger of that as Fort Collins or Loveland, even with (for now) cheaper home prices, given that Greeley remains a working and middle class city without as many high-paying jobs as its sister cities. More than a decade ago, as Denver workers moved to Greeley so they could afford to buy a house, and then Fort Collins residents began to do the same thing, Greeley was in danger of becoming a bedroom community.

Now that danger is there for all three cities.

“We want people who work in our community to be able to stay here,” Sowder says. “You don’t want them to feel forced to live somewhere else.”

That would, planners agree, be a hot mess, as a strained transportation system would crumble under all those commuters driving to, say, Fort Morgan or Sterling, in addition to our already crowded hubs. No one wants to be, say, Vail, a place where workers can’t afford to live.

All three cities are attempting to address affordable housing. Sowder looks forward to a Fort Collins work session with city officials, scheduled at press time for this month, to talk about the issue. Maybe that could mean encouraging Habitat for Humanity to build more homes, or somehow encouraging developers to build more affordable units, but those could be Band-Aids, given the limited inventory those agencies can realistically provide.

Another solution could be Fort Collins increasing its standards and funding for what it deems affordable, perhaps revitalizing the affordable housing program.

But, “how much do you want to subsidize?” Sowder asks. “That’s the question, and we are looking at all of that. I don’t have any real fast solutions at the ready.”

Loveland’s Housing Authority hopes to build more affordable units as well.

Mueller would rather talk up NoCoHousingNow.org, a coalition of all cities from everyone who touches housing wrestling with the future of housing costs in Northern Colorado.

“The problem will never end,” Mueller says. “It’s better to cooperate instead of tackle that issue on our own. Everyone independently thought housing was a big deal, so we had to consolidate that into one conversation. It underscores how significant it is for all cities in this region.”

The problem, of course, is nationwide, and not just in California, either, as wages continue to stagnate, but housing continues to rise. Mueller hopes for even more multi-family developments to crop up, with more condos, even if some residents dream for a house. He understands that, but he also believes those developments can give residents a lot of satisfaction.

“If they are well-designed, they can be great places,” he says. “You can walk to a park or walk through a doorway. You can still be neighbors.”