Communities Make Strides to Reduce Waste

By Dan England

Back in 1997, even those who devoted their lives to reducing the amount of trash that flows into our landfills thought the idea of zero waste was ridiculous.

Gary Liss remembers those controversial times, as he helped spark them. Liss was executive director of the California Resource Recovery Association when he organized the first zero waste conference in 1997. The name alone caused a stir.

“It caused quite a controversy within our organization,” Liss recalls. “They rolled their eyes and said that they would never see something like that in their lifetime.

Liss had embarked on a career of helping others achieve the goal, and yet, he understood the skepticism. Zero waste, after all, didn’t mean you could just burn the trash. That just released dangerous pollutants into our air. Remember, this was more than 20 years ago. Compacts discs were the most advanced technology the music industry could muster. Smart phones looked downright stupid compared to today’s models. Zero waste? That sounded like something out of The Jetsons.

Now our smart phones seem smarter than us and we use compact discs as coasters, and yet, Liss sees the same kind of eye-rolling skepticism at the idea of zero waste. But led by San Francisco’s example, which adopted the goal way back in 2001 and now leads the U.S. in keeping trash out of the landfill, there are cities comfortable with the term, even embracing it as a goal for the next couple decades. This includes Fort Collins. Liss, in fact, developed a plan for Fort Collins to make it happen.

Before you roll your eyes, too, Liss hopes you’ll hear him out. First, don’t get hung up on the term. Zero waste does not mean what you think it means. There’s an acknowledgement, at least right now, that trash simply can’t disappear.

“That’s why we do a lot of training on zero waste,” Liss says. “We really mean zero waste or damn close.”

Damn close, according to Liss, means 90 percent of a city’s waste isn’t burned or buried (landfills, as you may know, bury trash in cells that are typically lined to prevent leaching into the ground). Liss and others call that a diversion rate.

Indeed, 90 percent is really, um, close, especially when you consider San Francisco, the teacher’s pet of zero waste, achieves 80 percent. But Fort Collins hopes to achieve a rate close to that by 2030, and there’s an organization made up of Northern Colorado cities and Larimer County to help boost that goal.

If any of this still seems straight out of a 1960s cartoon about a space-age family, Fort Collins’ staff also believes it’s an urgent goal, and the fact that Larimer County’s current landfill will run out of room in 2024 isn’t even the biggest reason. Methane, the gas that makes you wrinkle your nose when someone toots, also leaks from decomposing trash in a landfill, and it’s a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. That’s right. Our trash is as responsible for causing climate change as our cars, our cattle and everything else that makes up our carbon footprint.

“Of all the initial things to come out of the climate action plan, more than 50 percent of the benefits come from zero waste initiatives,” Liss says, “and those can be achieved much quicker than the other projects, such as changing the way we get our energy and transportation.”

In addition to saving the world, and perhaps our species, there are those who simply want us to think of another way to dispose of our trash.

“In most places, we are still using caveman technology,” says Stephen Gillette, director of Larimer County’s solid waste division. “Burying trash has gone on for eons. If you would rather have a landfill, that’s an option, but people no longer subscribe to that.”

What Does It Mean?

The term “zero waste” has an appealing buzz to it, the same buzz that prompts executives to say “synergy,” but just like a double rainbow, no one seems to know what it really means.

“I bet you can find a whole lot of definitions for it, actually,” says Caroline Mitchell, a senior environmental planner for the City of Fort Collins.

Zero waste, like other buzz words, can create confusion, and it may even intimidate communities that haven’t had any discussions on waste diversion programs, such as Weld County. People paid to translate and speak for governments in Greeley and Weld expressed confusion over the term, even when Greeley does have a facility designed to help the public recycle so-called green materials such as yard waste, and Weld has a Hazardous Waste Facility that helps residents keep dangerous materials out of the landfill.

So, let’s leave it to Mitchell to help us sort it out, maybe even take some of the fun out of the term. She prefers the term “sustainable materials management,” a term she sheepishly calls “wonky” but helps define the idea behind zero waste.

“The challenge with the term is it seems as if we want to make sure there is no material going into the landfill, period,” Mitchell says. “That’s a narrow view of zero waste. The brilliance of it is thinking about the materials we use in a system.”

Loveland, after all, never uses the term in its daily operations, and yet Loveland led all of Colorado last year and will do it again this year with a 61 percent diversion rate.

“We’ve never sat down and said, ‘We’re going zero waste,’” says Tyler Vandameir, solid waste superintendent for the City of Loveland. “We’ve never labeled it. We just try to put good programs in place.”

Results are what matters, and that’s why Mitchell looks at zero waste as an ideal mindset more than a hard and fast goal.

“We do have a goal to get to the number zero, but I view zero waste as a goal like a goal of zero injury at work,” Mitchell says. “That doesn’t mean you won’t have injuries, but that is a goal, and you create systems with that goal in mind. That’s a vision we are all working toward.”

The Problems with Recycling

Not everyone chooses to do it, but everyone by now should know how to recycle. It’s probably the one important part of the zero waste concept that everyone knows. And that, Liss says, is a problem.

“It’s all about reduce, reuse and recycle,” Liss says. “But we’ve focused more on recycling than reducing and reusing, and that order is out of whack.”

Recycling does divert trash from the landfill, and you can’t have a zero waste program without it, Liss confirms. But there are many problems with it, including a reliance on a free market that doesn’t always support it.

“Before we would send everything overseas,” Gillette says. “Now they are saying, ‘No thank you.’ We have to open our own facilities to those materials now.”

Those materials aren’t doing well in the open market and are easily destroyed by the elements, such as water, or contaminated with food waste. There’s also still confusion over what can be recycled.

“Some of the materials we get here are what we call ‘Wish-cycling,’” Gillette says. “Those are things they wish they could recycle. I mean, bowling balls? Come on.”

Programs that focus solely on recycling, therefore, are in danger, even when things such as curbside recycling are an essential building block, explains Mitchell, and recycling offers incentives for residential consumers. In Loveland, for instance, consumers pay a required fee for recycling, but they also pay their trash based on the size of their container. If they recycle more, their waste container is smaller, and they pay less.

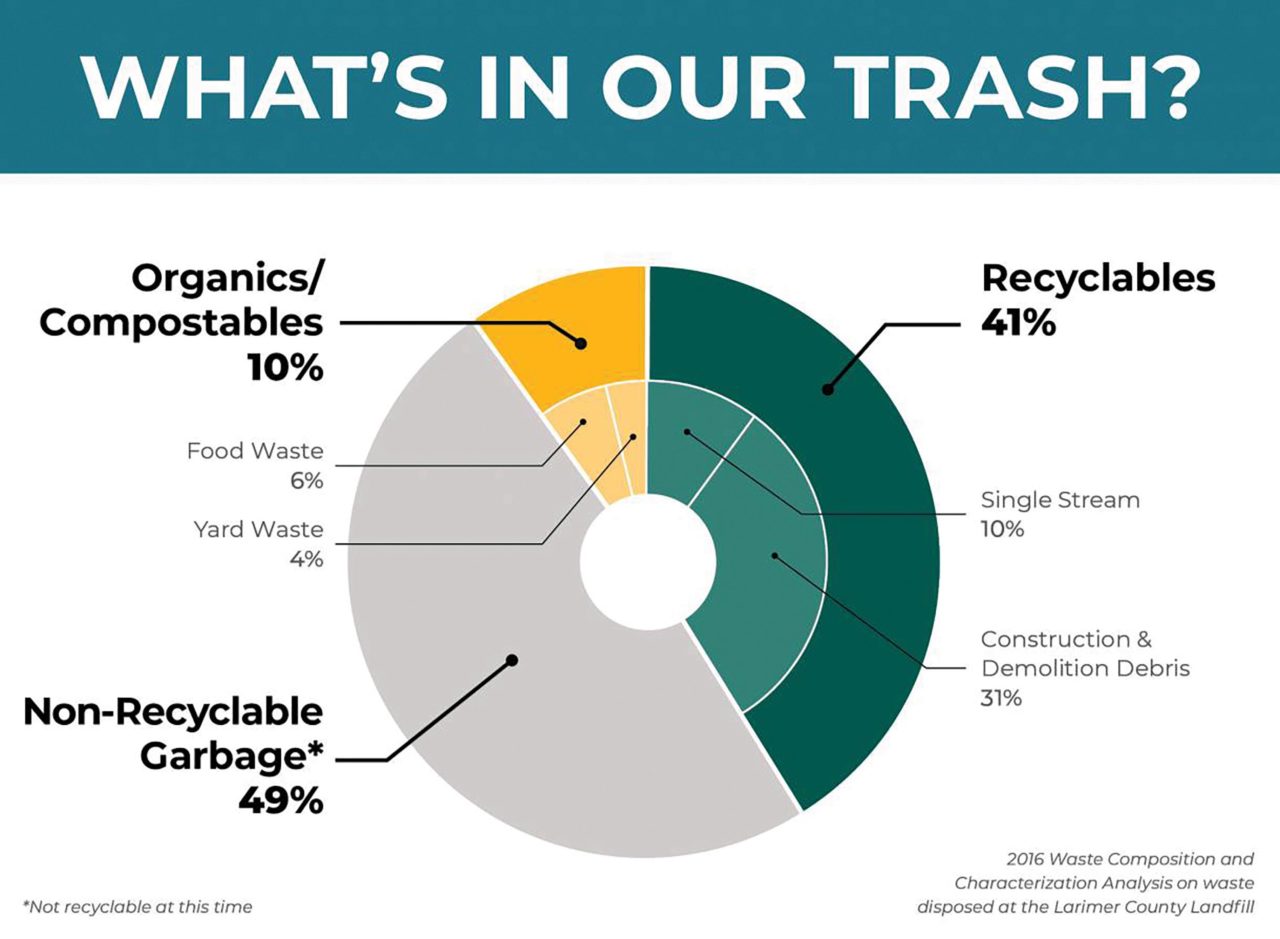

But there’s tremendous potential in composting. More than 50 percent of the waste generated in a household, mostly food and yard waste, could be composted, Mitchell says, and composting more would reduce the methane that contributes to climate change. There are even ways to use the methane gas for energy, as sewer plants have discovered. It’s the next big step in achieving zero waste, according to Mitchell, and doesn’t rely on the market to work.

Crawl, Don’t Run

The plan for the new landfill, approved last December, calls for a new transfer station, landfill, compost facility, demolition and debris facility, recycling center and food waste site at the Larimer County Landfill.

It may sound like Disneyland to someone like Oscar the Grouch, but Gillette cautions patience.

“We have to crawl before we run,” he says.

That means much of the fun stuff, including a facility for food waste and construction waste, probably won’t happen until 2024. But it also means the composting facility should be ready by 2021, giving Fort Collins time to establish a better composting program before the new landfill opens in 2023, a year before the current one is supposed to be full.

There’s also time to get creative with materials that could be recycled. Hailstorms shredded roofs all across Northern Colorado, for instance, the last two summers. Maybe there’s a way to turn all those singles back into oil for the roads.

“There are methods to do that,” Gillette says, “but right now, the pain isn’t worth the gain. Our landfill is full of shingles from the last couple of years. Technology has to catch up.”

That shows how hard it can be to achieve an aggressive zero waste plan. There’s recycling, and there’s composting, but once you divert 40 percent from the landfill, a realistic number that can be reached right away under the new master plan, it gets harder to move the diversion rate up. Even a percentage point past, say 70 percent, presents real challenges, says Gillette.

“Some of it is the low-hanging fruit,” he says, “and it just becomes harder and harder to handle some waste streams. Our country is based on use it up and throw it away. You have to change that mindset.”

The pact for the new landfill includes Larimer County, Fort Collins, Loveland, Estes Park and Wellington. Loveland, Gillette says, is the “poster child” because of its outstanding diversion rate, but it’s not fair to compare Loveland to Fort Collins because Loveland’s municipal government collects residential trash. Fort Collins, like most cities, relies on private companies to collect trash from residents and dispose of it.

“Loveland has a lot of control over what’s happening,” Gillette says. “The other entities rely on private companies, and that’s not a bad thing, but they have to ask their trash haulers about the policies they want.”

Vandameir doesn’t believe his public trash service makes it easier for his city. “We just have really good outlets for recycling, and when they were put into place, it all worked. I don’t know that any of it was easy. It took a lot of thinking and effort.”

“I’m biased,” he continues, “but from everything I’ve seen in the mountain west region, [Loveland] stands alone in how it’s designed. We emphasize good programs and easy methods and try to get stuff out of the trash collection.”

Pushing for Public Support

Fort Collins can study cities in Italy that have a diversion rate of 90 percent (yes, really), look at California and how it does things (it’s top in the U.S.) and sift through their own trash to see what residents are throwing away (yes, really) to find gaps in services that companies could provide. Maybe, for instance, there’s a company that specializes in turning those roof shingles into oil.

But unless Northern Colorado residents buy into the program, zero waste won’t happen.

“It’s critical,” Liss says. “We can’t get there unless everyone joins in.”

Businesses have an additional incentive for reducing waste, as they save money, but residents may not see the same benefits—even if they are there, as they are under Loveland’s program. Up to 20 percent of a population won’t recycle, for political or personal reasons, Liss says, and there’s always up to 20 percent who will regardless of the cost and effort.

“It’s the mid-range that you need to assign programs to, to make it easy, convenient and affordable,” Liss says. “When you design the programs right, people want to do it, and they will.”

Beyond those recycling and composting programs is that next step. That’s where Mitchell hopes the Fort Collins residents she works for, and all residents of Northern Colorado, begin to think about other ways to keep trash out of the landfill.

Residents have a lot of power in their purchasing, more than they probably realize, she says. “Every person handles some sort of waste material and makes some sort of purchasing decision nearly every day. So, every time we make the choice of what we will purchase and how we will dispose of it, we are participating in a zero waste system.”

If a product smothers itself in packaging, then consumers don’t have to buy it. Or, if they buy it, they can contact the company and let it know they are unhappy with the packaging. Sometimes residents can even return the package it came in so it can be used again.

“When we go beyond the basics of whether you recycle the can in your hand, and when you start to talk about consumer choices, that’s when we get into fundamental conversations,” Mitchell says.

Fort Collins residents made it clear they wanted their government to be aggressive about reducing its waste, and the city responded with a plan for zero waste. Now it’s time for them to show how far they’re willing to go. Mitchell, so far, remains optimistic.

“The great thing is everyone can participate,” she says. “They can go as deep as they want, and whatever they do makes an impact.”

SIX THINGS YOU CAN DO:

1. The most obvious is also still pretty darn important: Recycle as much as you can, and if you take part in composting, that’s even better.

2. Resist the urge to just throw something away. Recycle it, reuse it or donate it to a place that will use it again, such as a thrift store or another charity.

3. Use your purchasing power to reduce waste: Contact a company or don’t buy products that use excessive packaging or materials that can’t be recycled.

4. Live in cities that support it.

5. Don’t let others get hung up on the term zero waste. Educate them when they say it’s a space-age goal. Just say the real goal is to reduce waste.

6. Vote for candidates who support policies that help achieve the goal of keeping trash out of landfills.