College ballplayers chase diamond glory in NOCO.

by Neil Devlin

Like so many other people in recent years, Cole Emerson found what he was looking for in Northern Colorado.

But he didn’t come for legalized marijuana, champagne powder, a start-up fortune or a second home with mountaintop vistas. The 20-year-old from Tecumseh, Kansas, is here for an entirely different reason.

Baseball.

It may not rank high on the list of attractions that bring people to NOCO. Baseball isn’t even the region’s most popular team sport – football, hockey and soccer all have bigger followings here. But Emerson belongs to a growing fraternity of college players who spend the summer playing ball on the Front Range in the Mile High Collegiate Baseball League.

One of dozens of summer col- legiate leagues spread out across the country, the MHCBL is an increasingly attractive destination for post-prep players hoping to get to the next level. Although it’s younger and less well-known than Colorado’s other summer college circuit (the Rocky Mountain Baseball League), the MHCBL has a broader geo- graphic reach and a bigger NOCO presence. Four of the league’s 10 teams are based in Larimer and Weld counties, playing home games at City Park in Fort Collins, Nelson Farms in Johnstown, and Frederick High School.

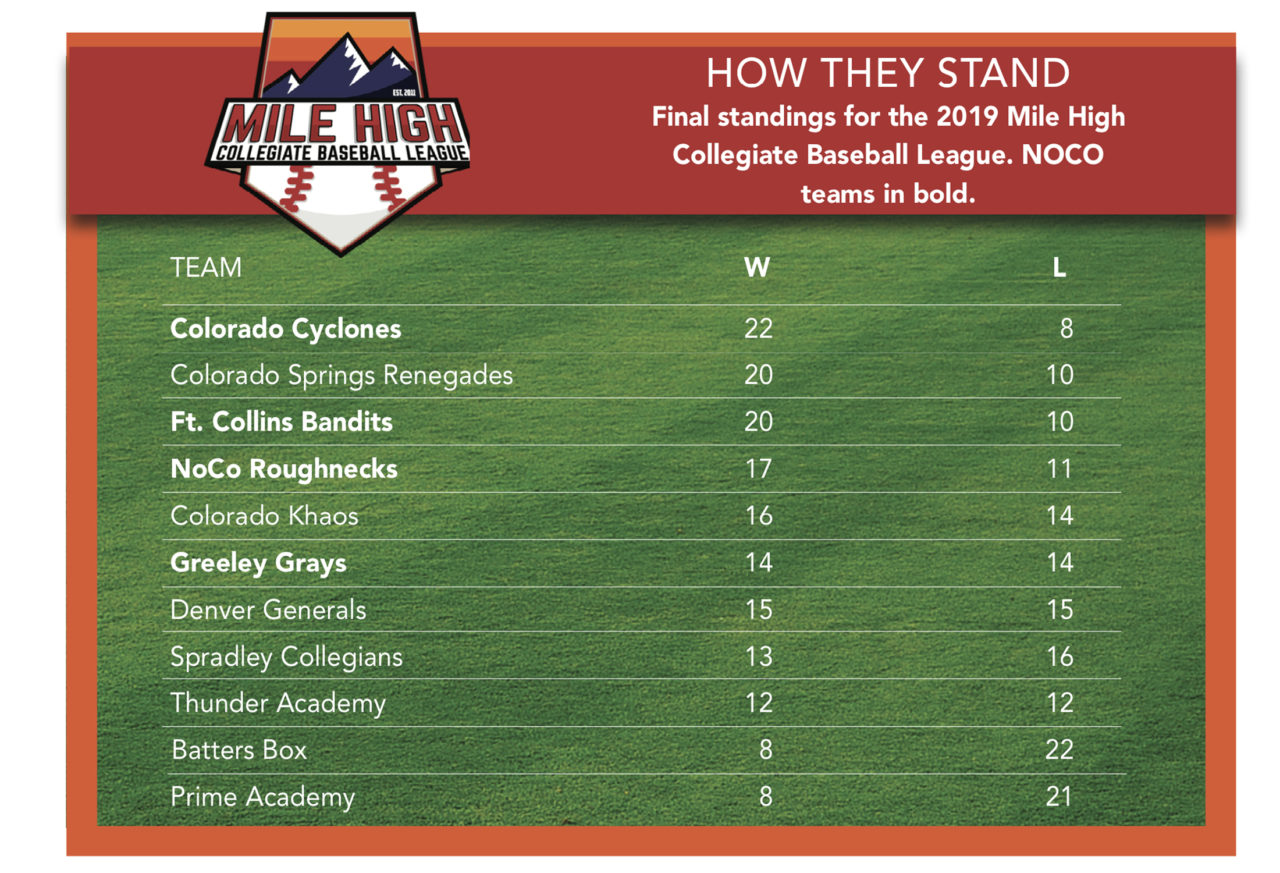

The MHCBL is on the rise, thanks to the league cham- pion Colorado Cyclones’ fifth place finish last summer in the prestigious National Baseball Congress World Series.

“Everyone told me this is a good league,” Emerson says. “It’s good competition, good baseball.”

An outfielder for Washburn University (an NCAA Division II school), Emerson just completed his first MHCBL season with

the NOCO Roughnecks. Like most of the league’s players, he’s not a highly regarded pro prospect – not yet, at least. But the MHCBL is designed to provide young men like Emerson with extensive instruction, high-level coaching, and the chance to improve their games and catch a pro scout’s eye.

“I came here with the idea that this would not be a walk in the park,” says Emerson, a redshirt-sophomore-to-be who joined two Washburn teammates in the MHCBL this summer. “So far, that has been true.”

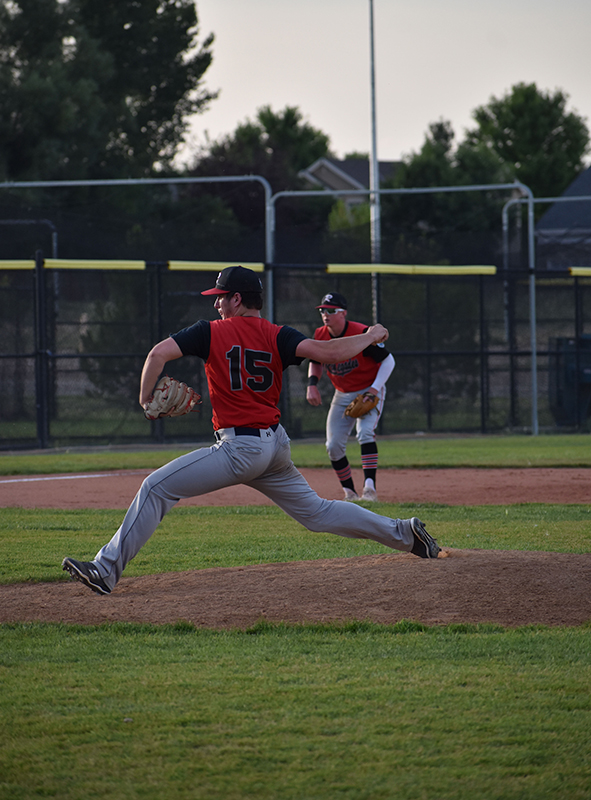

The MHCBL is a natural fit for Colorado natives like Micah Bregard (left), who pitches for a Delaware junior college, and Sam Cregan (right), who plays for Augustana College in Illinois.

LEADING THE LEAGUE

The MHCBL and RMBL are Colorado’s answers to the renowned Cape Cod Base- ball League. Long recog- nized as the premier summer college circuit, the Cape Cod loop enjoys financial backing from Major League Baseball, a primo East Coast location and a roster of high-profile alumni that includes more than 1,000 big-leaguers. It has been the subject of multiple books, several documentaries and a Hollywood rom-com (2001’s Summer Catch).

The MHCBL has sent two players to the major leagues (including Colorado Rockies pitcher Kyle Freeland), and about a dozen of its players have been selected to the MLB draft. And it’s owned by retired former Rockies pitcher Jason Hirsh.

“There needs to be a better option for summer,” says Hirsh, a second-round draft pick who spent two years with the Rockies (2007-08) and started 19 games for the franchise’s lone pennant- winning team. “Kids [need] a kind of developmental league, working on things and not having to worry about results, and getting an appropriate amount of play- ing time.”

Hirsh has been working with young players ever since injuries forced him to retire in 2010, two years shy of his 30th birthday. In 2013 he launched FAST Baseball, a Denver training facility that specializes in the care and healthy development of young pitchers’ arms. He also began working as an informal pitching consultant for the MHCBL, which was founded by a trio of Colo- rado baseball lifers: Kent Gregory (a longtime instruc- tor for the Yankees and Mets), Doc Ritterbusch (who coached Freeland at Den- ver’s Thomas Jefferson High School) and former Denver Zephyrs general manager Tom Maloney (later a scout for the Dodgers and Royals).

When they asked Hirsh if he was interested in taking charge of the MHCBL prior to the 2018 season, he jumped at the chance. “This would be a fabulous opportunity to run things the way we want to run them,” he says.

Billing itself as “the nation’s premier developmental summer league,” the MHCBL prioritizes instruction and health over wins and losses. The league’s website touts the MHCBL as “a steward of collegiate athletes” with an obligation to help players “return to their programs in better condition than they arrived.”

“We’re actually borrowing the players from the colleg- es,” says league co-founder Gregory. “The thing is, you get a pitcher from [Colorado Mesa] and they have to feel comfortable that we’re going to take care of their guy, not overpitch him or abuse him. We had to have a program in place for that pitcher to have the best chance to get better.”

The league attracts players from all levels of com- petition, including NCAA, NAIA and NJCAA. MHCBL coaches are required to distribute playing time as equitably as possible, ensuring that everyone on the roster gets significant experi- ence. “This way, a player doesn’t pay his money and get benched,” says league president Amanda Kubec, who oversees operations and logistics.

Player fees average less than $1,000, although it var- ies for position players and pitchers. In addition, each team pays a $3,000 entry fee per season to cover expens- es such as fields, umpires, equipment and uniforms. Rosters usually contain a high of 28 players, and the season runs from 30 to 35 games. The league champi- on is eligible for the National Baseball Congress World Series, held each August in Wichita, Kansas.

That team has come out of NOCO in each of the last five seasons.

Garrett Mayers hope to catch a scout’s eye in the MHCBL.

Drake Logan hope to catch a scout’s eye in the MHCBL.

ALL-STAR ASPIRATIONS

The Colorado Cyclones, based in Johnstown, are owned and coached by Greeley native J.L. Buchan- an. A graduate of Greeley West High and the head coach at Taft College in Bakersfield, CA, Buchanan has led the Cyclones to the last five MHCBL titles. The 2018 team went deep into the NBC World Series, reach- ing the national quarterfi- nals before dropping a 9-8 heartbreaker to the eventual tournament runner-up.

“It gives our guys a reward for doing so well,” Buchanan says, adding “it’s probably why we are able to get more out-of-state guys.” Buchanan scours prep all-state lists and college rosters for talent. His 2018 team featured players from more than a dozen states, along with stars from in-state schools such as the University of Northern Colorado and CSU-Pueblo.

“We don’t get a lot of kids from UCLA or USC, but the Cyclones bring in some D-I guys,” Hirsh says. “We get them from the smaller D-I programs and D-II, D-III and NAIA. We definitely have better hitters than pitchers and would like to bring in more high-quality arms.”

As the league’s reputation and popularity have increased, so too has its level of play. Like Emerson, most players jump at the chance to join.

Henry Haen, a graduate of Denver’s Mullen High School and now a first baseman at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, had no idea of the MHCBL’s existence until he found out about it from some of his college teammates. He played alongside Emerson on the Roughnecks this summer, and he couldn’t have been happier, even though he had to commute from Colo- rado Springs for practices and games. “Honestly, it has been really good,” he says. “I’ve seen a lot of good pitchers and some others I will see down the road [in college play], which is nice.”

Haen wasn’t happy with the summer league he joined in 2018, he says, because it was “more concerned about wins and losses” than player development. In the MHCBL he made noticeable strides in his game, particularly in his footwork and hitting.

Evan Richards, a Colorado Cyclones outfielder from Smoky Hill High School in Aurora, says the MHCBL “is a good time. My team does a lot of recruiting because we want to compete, but it does offer a lot of instruction.” Teammate Foster Gifford, a right-handed pitcher out of Brighton High who’s headed to Wichita State’s storied baseball pro- gram this fall, says the Cyclone coaches “have a little different perspective. They build you up and make you want to do more on your own. They know a lot about the game and put you into situations to fail and learn. They really help you.”

College coaches agree.Nick Childs, the UNC pitching coach and recruiting coordinator, recommends the MHCBL. “I think it is a great resource for Colorado kids,” he says. “Guys can come back here and live close to home and play a good collegiate schedule. It has some unique aspects – guaranteed roster spots and pitch counts – and is in tune to what’s important to summer ball.”

Colorado’s appeal as a sum- mer destination remains an important factor in attracting talent. The NoCo Roughnecks had four out-of-state players this season, and in prior years the roster has included players from as far away as Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

“I like seeing the growth of the league,” says Hirsh. “We need to keep doing what we do.”

All of this is taking place in a state that has only two Division I baseball programs, at UNC and the Air Force Academy.

If CU and CSU were to add programs, says Haen, “it would completely change the base- ball landscape here.”

The Cyclones won their fifth straight MHCBL crownand head back to Wichita this month for the NBC World Series. The roster features former NOCO prep star J.T. Mossberg, who helped pitch Eaton High School to a state title in 2015; University ofNorthern Colorado outfielderMatt Burkhart, who also played for Eaton’s championship team; former Greeley West star Luis DeLeon; Fort Collins High School alumnus Quinn Tomasino; and Berthoud native Josh Archer, who pitches in NCAA Division I for Belmont University.

However the Cyclones fare in the NBC tournament, the MHCBL is a league worth watching.

“You get to play against some good competition,” says Cole Emerson. “I do love it here.”