Jeffrey Albert’s mom never quit.

That’s what keeps the cancer doc going.

Jeanne Wolfendale was not well, not at all, but she wanted to see this strange new life her son was nurturing within himself. So she accompanied Jeffrey Albert out to the Blue Sky Marathon, where he would run 26 miles over dirt, up hills and through bony rocks.

Albert, a driven, intelligent son, had pushed himself hard his whole life. Though cancer could be hard, even evil – the terminal disease destroying Wolfendale was proof of that – he liked being someone who could help patients through it.

Trail races were yet another way to push himself. They challenged him far beyond the point where he was comfortable. But they were also a way for him to relax. He had a promising career as a radiation oncologist for Banner Health, and a family that included three young children. Running on dirt gave him the kind of peace he’d sought out years ago on his way to medical school, when his wife, Erin, needed another semester to finish college, so he rented a car and drove west. He’d never been farther west than Chicago and had never seen the mountains, but he had $1,000 and what he called a naive wanderlust to go on an inexpensive adventure to see the world.

It was so out of character for him, but that’s what made it so beautiful. It was exactly the kind of opportunity he and Jeanne couldn’t have growing up, when bills brought tears and she had to fight to keep food on the table.

He spent three weeks hiking and sightseeing and sleeping in the rental car at national parks. Many people go on that sort of trip to learn something about themselves, and Albert did indeed discover something deep inside him. He learned he had to live close to the mountains.

“I don’t really know what led me there, but once I saw the mountains, I connected,” Albert said. “I changed.”

He went to MD Anderson, one of the top-ranked schools in the world for cancer care, and whenever possible he’d squeeze in a hike during conferences in states that had places to go. When North Colorado Medical Center offered him a job, he took it because it seemed like a growing program – but mostly because you could see the mountains from Greeley.

Albert began running because he became frustrated with those hikes. He wanted to see more of the mountains, yet his range was restricted by fitness and the limited time he could spend away from his family. Running gave him the engine to travel farther and faster. Eventually trail running let him have it all – the beauty, the challenge and the grit displayed by his mother in all those years of raising him.

Back at the Blue Sky Marathon, he cramped up and fought those hills, but he finished, and something clicked with him. This was what he needed. This was his thing.

It was the last time Albert would see his mother anywhere but in a bed. She died a month later at age 59. Running became a way to grieve – to think about, for the first time, all she did for him. It was also a way to connect with his mother’s grit. It reminded him of her.

After a year, some races and a solid footing in the sport, he thought about the time he’d taken his mother to Steamboat Springs during a ski trip, the kind of experience he enjoyed sharing with her given their hardscrabble background. On a return visit to Steamboat, he emerged from the swanky ski resort and looked up to the top of Mount Vernon.

He knew Run Rabbit Run, a 100-mile race, began with a slog up to the top of the mountain. Albert promised himself that one day, he would once again share that place with her, at a race he would do for himself, leaving some of her ashes at the top.

“I just told myself, ‘I have to give this a shot,’” he said.

NCMC proved those instincts right. Last summer the hospital announced a partnership with MD Anderson and put Albert in charge of the cancer unit at the new Banner MD Anderson Cancer Center.

It was a big step for him in a year full of them. The announcement came just a few weeks before he would attempt Run Rabbit Run on September 15.

Ultraunners talked to him about a 100-miler the way road racers talk about the marathon: It’s the apex of the sport, the ultimate challenge.

“Among the community, I heard that I had to run a 100-miler from so many,” Albert said. “They told me it would change my life. In that sport, there are people who have done it and people who haven’t.”

In many ways, the race didn’t appeal to him. He was terrified to run at night, and he didn’t know how he would drink and eat enough to keep his body moving in, say, the 28th hour of running. And that is, of course, what pushed him to think about it. He found that challenge “intriguing,” just as he had found any challenge in life.

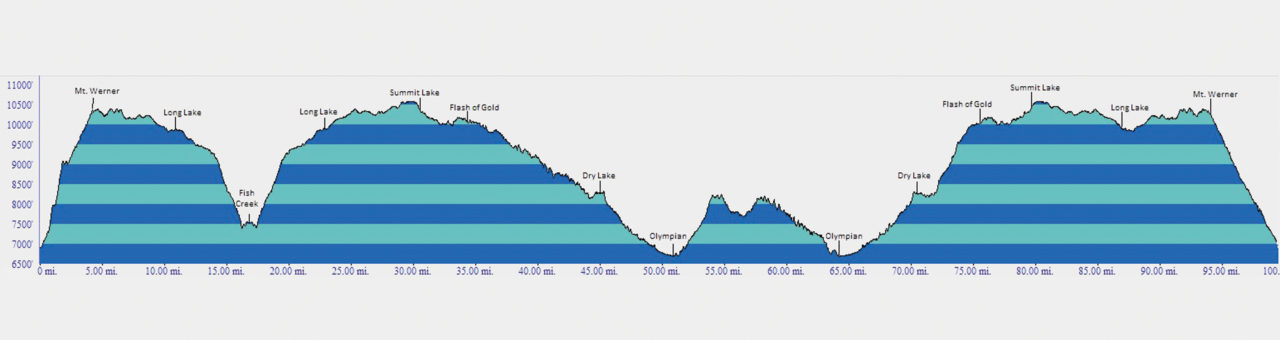

He trained hard because that’s what he does, and he entered the Never Summer 100K as a test run. It was … fun. The race traversed a wild area and offered the views he loved, and he felt good. He expected to feel the same way on the trek up Mount Vernon. But that race presented its own challenges.

In a 100-mile race, one of the most important things you can do is to limit the negatives. That sounds, well, negative. But in a race that long, tiny things become big – like a piece of your shorts rubbing inside your thigh, forgetting to drink at a couple of aid stations or ignoring a blister on your toe.

Because of who he is, Albert had many of those little things covered. By mile 50, he was feeling so good that he figured it wasn’t really a question of if he would finish, it was more of a question of when. But as the day went on, he realized the one thing he couldn’t control would challenge him the most.

It was hot. The temperature climbed to 88 degrees on a course that offered almost no shade. On a beach, in a swimsuit, with water nearby, 88 degrees feels fantastic. Albert was running through a dusty course in direct sunlight with sweat pouring out of him. It did not feel fantastic. He could barely drink enough to keep his blood from turning into sludge. When the sun relented for the night, he felt drained, especially on a long climb in the dark.

Albert didn’t have one of those famous dark moments that ultrarunners whisper about over post-race Gatorade. But at mile 85, sitting with his head between his knees, he did wonder whether the final miles were worth it. But then he thought of his mother’s grit, and decided they were.

When he reached the top of Mount Vernon again, and the last aid station before the finish, he was so excited that he forgot to leave his mother’s ashes. The next day, as he was hiking around Lake Anges, a stop on the way home from Steamboat, he saw his mistake as more of a sign. Albert is not an especially spiritual person, but ultrarunning helped him explore his feelings about his mother and gave him the time to think about her impact on his life.

He found that connection with her, that grit, and that was a large part of his healing from her death. It still is. But he also recognized that his mother wouldn’t want him spending so much time away from his family for such an individual pursuit. His mother had spent most of her life focused soley on him.

“She was devoted to us, and so she wouldn’t want me to run around the mountains,” Albert said. “That’s my version of this. She would want me spending time with my kids.”

Erin works as a manager for a bioengineering company. She can do the work from home, but that means she’s busy, too, and needs help with their three kids, Parker, 4, Caroline, 2, and Owen, 1. The 100-milers can’t continue, she told him recently, with the exception of the Western States 100 or the Hard Rock 100, two one-of-a-kind races that are hard to get into through the lottery system. If he wins a spot in one of those, he will go. Otherwise, he will have to wait until the kids are grown and perhaps satisfy himself with another Never Summer 100K.

As a way to enjoy the time off from long runs, and perhaps to fulfill his mother’s wishes, he took Parker up to Horsetooth Falls last fall. Parker is now an accomplished hiker, especially for a kid his age. Albert asked him if he could make it all the way. After some thought, Parker said he could – if he had five snack breaks.

Sure enough, Parker got to the top of the falls. Albert gave him his final snack break. He left his mother’s ashes at home.