Not so long ago, that kind of experience was very hard to find in NoCo’s sprawling, spread-out communities. But things are changing. Pockets of walkability are springing up everywhere from Fort Collins to Fort Lupton, bringing pedestrians, cyclists and other self-propelled travelers to areas not traditionally known as bastions of non-motorized mobility.

The pace of this transformation resembles a casual stroll more than an all-out sprint, but the tempo seems to be quickening. City and county planners in various corners of NoCo have been working for years, and in some cases decades, to encourage denser development patterns that reduce people’s reliance on cars. Those long-range plans are beginning to take shape, pushed along by a number of trends. Demographic change is one major driver. Walkable neighborhoods appeal to two of NoCo’s fastest-growing population segments – empty nesters seeking more relaxed lifestyles, and residents under 40 (especially families with young children) who want to keep active both physically and socially. Another factor is the growing concern over global climate change, and the resulting preference for sustainable communities with light environmental footprints.

“The Bucking Horse community is a prime example,” says Kyle Basnar, a realtor and broker associate who was born and raised in Fort Collins. “They have neighborhood features such a local brewery, a gym and coffee shops. That ability to create

The Montava development in northeast Fort Collins promises to incorporate many of the same values on a broader scale. The 4,000-home master-planned development plays up New Urban themes, with compact neighborhoods linked to commercial centers and open space via a network of footpaths and pedestrian-friendly corridors. Should it gain City Council approval this spring and clear funding hurdles, Montava would be a big step torward a more walkable NoCo.

Along the same lines, Windsor’s planning department is working on the community’s first comprehensive transportation master plan and expects to put it into effect within the next year. “[It] will address all modes of transportation, including pedestrians, bicycles, transits and others,” says Scott Ballstadt, the community’s director of planning.

“I see having a walkable community as a great benefit,” adds David Eisenbraun, a strategic planner for the city of Loveland.

Why Walkability Matters

Studies have correlated walkability with a high quality of life. Benefits span a wide spectrum and include health and fitness, social cohesion, public safety, air quality and noise reduction. The health benefits seem particularly pronounced, which is why public health departments often play a role in promoting walkability. One investigation tracked individuals who relocated from car-dependent communities to more walkable neighborhoods. After moving, the research subjects showed statistically significant decreases in body-mass index and age-related weight gain.

“There are a wide variety of benefits,” Eisenbraun says. “Some are measurable, and some are felt. Typically, people feel healthier and happier when they are out walking and enjoying their surroundings, although this can change with seasons and can be challenging to quantify. The environment also benefits from less motorized forms of transportation.”

“Walkable communities benefit different segments of the population,” adds Paul Hornbeck, a senior planner with the Town of Windsor. “Schoolchildren and seniors may be unable to drive, so they rely on other methods of getting around. Walkable designs can also reduce the risk and severity of accidents between motor vehicles and people walking.”

How walkable are Northern Colorado communities today? The answer starts with another question: How is walkability defined and measured?

One widely used tool, http://www.WalkScore.com, bases its calculations on the distance a pedestrian would have to walk to fulfill basic life tasks. Using GIS data, it assigns a

WalkScore for any given location (on a scale of 0 to 100) by gauging the mileage to destinations such as grocery stores, schools, parks, restaurants and retailers. Destinations less than a quarter-mile away get maximum points; those a mile and a half or further get zilch. The overall score is based on dozens or even hundreds of walking routes.

WalkScore’s strength lies in its geographic specificity—you can get an individual score for every house on a given block. But its weakness is the complete neglect of qualitative factors that can make all the difference between an enjoyable walk and a miserable slog. No adjustments are made to account for the type of terrain, width of sidewalks, scenic values, volume and speed of nearby traffic or the presence of obstacles such as highways and waterways.

Downtown Fort Collins has the region’s highest WalkScore at 79, deemed “Very Walkable.” https://www.redfin.com/city/7006/CO/Fort-Collins/housing-market#transportation.

It’s not quite downtown Denver (WalkScore: 91) or downtown Boulder (97), but it’s up there. The overall City of Fort Collins scores just 36 – “Car-Dependent” by WalkScore’s rubric. Greeley checks in at 40, and Loveland sits at 30. Those figures lag the scores for more densely developed cities such as Denver (61) and Boulder (58), not to mention smaller, more compact rural towns such as Fort Morgan (81), Lamar (68) and Sterling (77).

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has its own walkability index, which is a little more generous to NoCo communities than WalkScore. The EPA’s scale rates each census block on a scale of 1 to 20, with anything between 11 and 15.5 considered “above-average walkability.”

This label applies to good-sized swaths of Fort Collins, Greeley and Loveland, as well as to the downtown cores of smaller towns such as Windsor, Milliken and Berthoud. Each city has at least one cluster of restaurants, coffee shops, libraries, civic centers and other attractions that are within walking distance. In a few cases, microbreweries have given rise to what might be termed “microwalkability,” serving as magnets that attract nearby food, shopping and entertainment destinations. Still, the objective measures of walkability illustrate how far NoCo communities have to go. For a look at some of NOCO’s most walkable neighborhoods, see the map on pages 32 and 33.

The Path Forward

In addition to boosting the overall health and wellness of a community, walkability also increases the value of real estate. “There’s always more drive to a community that does have more walkability,” says realtor Kyle Basnar. Asked if walkable destinations affect home values, he nods emphatically: “They definitely do.”

McKinnon notes that prospective home buyers routinely ask him about future planning, wondering if parks, schools or shopping districts are on the drawing board. When the answer is yes (as it often is in NoCo these days), the response is generally favorable.

“I’ve seen it [walkability] starting to trend more,” Basnar says. “Builders and developers have seen more success with this model. It really comes down to cost and making it work. With the demand being there, they are going to try to create more neighborhoods with that concept. I personally hope we see a ton more because people want to live in these areas.”

“As more homes are being built and cities are growing north and east, future planning comes from the city, and I think cities are up for the challenge,” McKinnon adds. “We’re a low-inventory market in NOCO, even though the market is adjusting. It can be a little challenging to place buyers in these walkable communities. But it’s getting easier.”

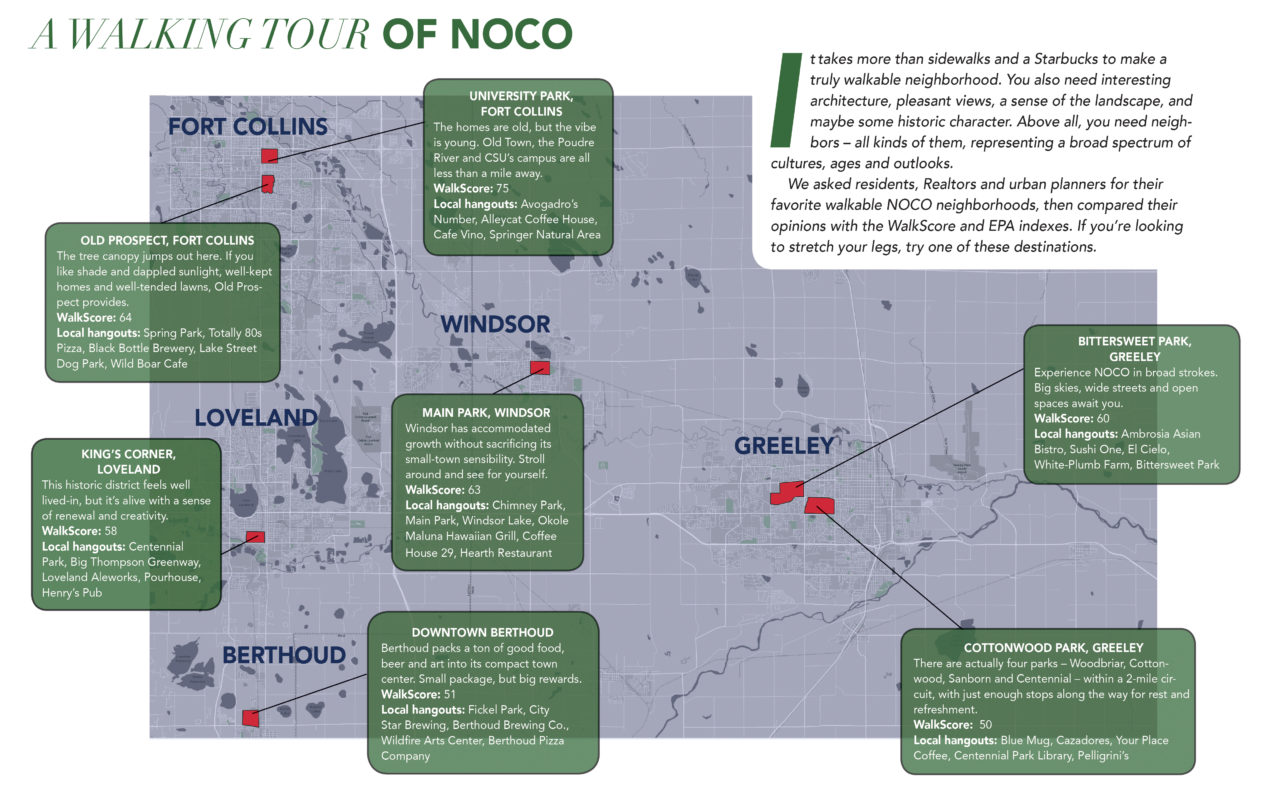

We asked residents, Realtors and urban planners for their favorite walkable NoCo neighborhoods, then compared their opinions with the WalkScore and EPA indexes. If you’re looking to stretch your legs, try one of these destinations.