Just hours after he’d fallen off a cliff, broken 17 bones and sliced a third of his back open, Dave Beegle’s bone doctor gave him some encouraging news. He’d probably make a full recovery.

This empowered Beegle to ask what he now says was a stupid question: Could he play a gig in two months?

Beegle was grateful to be alive that day, on May 18 of last year. He’d fallen 60 feet and tumbled twice that far down the hill. He counted five catapults after the first long fall, and every time he bounced off the hillside, his body made a loud crack, like a branch falling from a tree. A pair of tall rocks caught him and likely saved his life.

When his wife, Sandy, found him a mile or so from their home in rural Loveland, she couldn’t believe how far he’d traveled from where she thought he’d fallen. He looked like a speck against the landscape.

“My only thought,” Sandy says, looking down from the cliff and figuring out how to reach him, “was to get to him before he died.”

Once Beegle was in the hospital and knew he was going to live, he began to take stock. The bone doctor had been able to put his Humpty-Dumpty body back together using plates and screws. He used so much metal in Beegle’s mangled arm that he called it a personal record. And yet Beegle had dodged the kinds of injuries that would mess with his career as a guitarist.

His hands were fine. He didn’t break a finger. Heck, Beegle, a finger picker, didn’t even break one of his long acrylic nails. So…about that gig?

The doctor looked at him and smiled.

“I don’t see why not,” he said.

The same day he fell, Beegle began piecing his life back together.

Dave Beegle at the hospital after his accident.

A prodigy and disciple

Beegle wrote his first song on the piano at age 6. Both of his parents played too, his father well enough to dream wistfully about a career. Beegle took piano lessons until he was 13, when his life changed.

Black Sabbath released their first album, and Beegle was inspired to play the guitar. He got good at it, and then he became good enough that he got noticed both locally and nationally. He eventually got good enough that in 2020 he was able to buy a house with Sandy and their daughter, now 17, in the shadow of Devil’s Backbone, with a full recording studio surrounded by a dozen guitars.

The gig that became his goal while recovering from the accident was with William Topley, who was the lead singer of the British group The Blessing in the early ’90s. It was the kind of opportunity Beegle gets fairly often: He’s known for both his work with rock ‘n’ roll bands such as The Jurassicasters and a solo career of acoustic guitar playing world music and flamenco.

Last May, however, he simply wanted to go for a walk in the hills behind his home. He enjoyed spending his early mornings on these hikes instead of in a gym.

He’d typically start about 100 yards up his driveway before he’d huff up a hill, then another and finally over to some cliffs he liked to scramble over. They reminded him of Moab, a favorite place of his, and he liked the views the cliffs gave him, including the elk and turkeys in the valley below. There was a certain magic to it, like playing music.

“I’m not a death wish guy, but I like being on point,” Beegle says. “There’s a focus there, like what you feel during a big gig.”

That day, Sandy decided to join him. It was a pleasant surprise. Sandy liked to sleep in. She hadn’t hiked the area with him in a year.

When she made her way up the hill and approached the cliffs, she couldn’t find him. So she texted him.

“Are you hiding from me?” she asked playfully.

One wrong move

Beegle had scrambled over one particularly tricky traverse 100 times, but that time, he missed a hold. There was no slow motion, like they do in the movies. He was there, and then he was falling.

“I still can’t figure out what happened,” Beegle says. “I remember my left foot slipping, and then I was in motion.”

He was aware of what was happening as he fell and tumbled, and he heard the cracks of his body but felt no pain. When he came to a stop, against the rocks, he checked his phone, and it was in equally bad shape. He began to call for Sandy. In between his yelps for help, Beegle, who is a man of deep faith, prayed.

When Sandy arrived at the cliffs, Dave wasn’t there, and a cold dread washed over her playfulness. As she gazed along the ridge line, she began to look down.

“There just wasn’t any other place he could be,” Sandy says.

She expected to find a body. Instead, she heard his faint cry. She called 911, told them they’d need a helicopter and plotted a way to get to him by taking a back road at the end of the cliffs, a route only a resident could find. When she reached him, she remained calm.

“I didn’t want to be the hysterical wife,” Sandy says.

When help arrived, Beegle began cracking jokes about cliff diving. That reassured her. He didn’t look like Dave, but Dave was still there.

A new beginning

No matter how lucky he got—avoiding paralysis, death and a debilitating brain injury—17 broken bones is still a fair amount, so he spent four weeks in the hospital. A GoFundMe organized by friend Jeremy Howie, who took guitar lessons from Beegle, raised nearly $50,000 to help him cover medical bills and the time off work. When he was released, Sandy was glad to have him home. He’d had so many visitors that she never got to spend any time alone with him.

A few weeks later, he played that gig with Topley, and at the end of the two-and-a-half-hour show, he was exhausted. But he did it.

Now he has most of his energy back. He eats well and stays active, though he doesn’t plan to visit the cliffs again.

“Don’t take things for granted,” Sandy says. “All those things you say sound cliché, but when you really know what that is, what it means, it’s deep.”

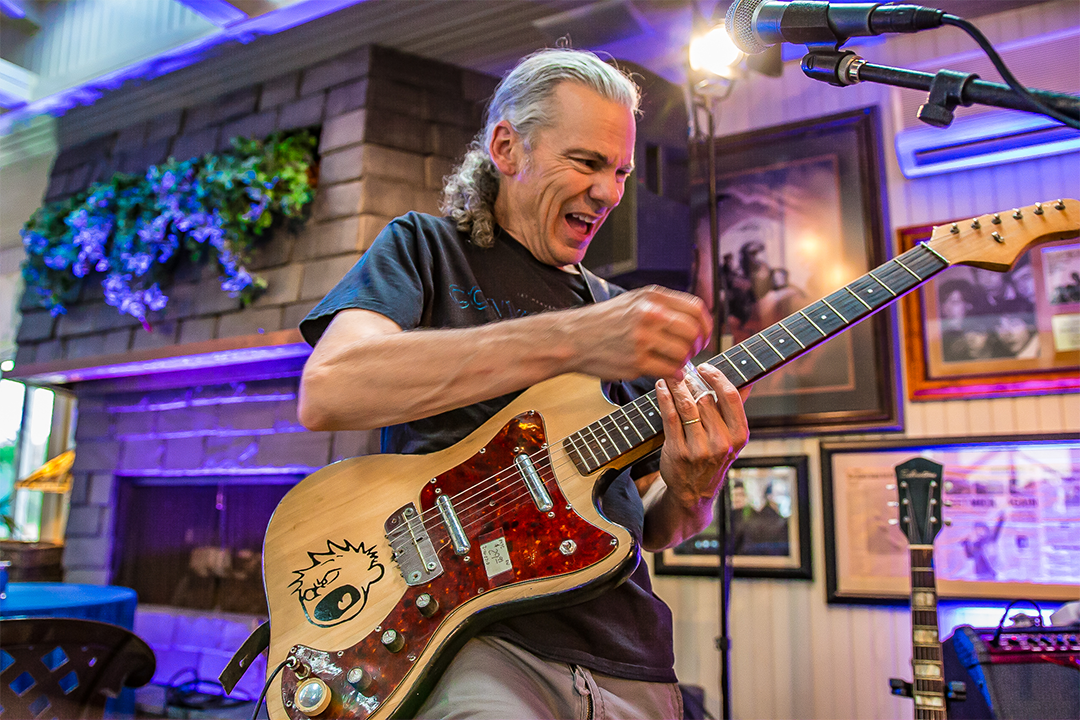

Beegle plays, produces and records regularly, and at 63, he finds inspiration from people like Paul McCartney and Willie Nelson, who are still making music in their 80s and 90s.

“I want to enjoy the mystery and magic of music my whole life,” Beegle says, “like I did as a kid.”

He doesn’t feel much from the accident other than gratitude from all his supporters, the doctors and God. Doctors attribute part of that to his hard work getting ready for that gig, playing guitar for hours as soon as he got home from the hospital.

He remembers walking through his front door for the first time after the accident, limping into his studio and grabbing a guitar. The first song he played was “Here Comes the Sun.”