At first glance, Wolverine Farm Publick House looks a bit like the house on your block where the eccentric neighbors live. In the foreground of its wooden façade is a gated patio containing garden boxes, picnic tables and a pergola dressed in string lights, plus a wall piecing large magnetic words together the way you’d normally see them on a refrigerator. But as you get closer, you’ll notice a sign advertising coffee and beer as well as an open garage door revealing a bar. And the moment you step inside, you’ll realize it’s much more than that.

The building, nestled among an auto upholstery shop and apartment complex on Willow Street, houses a publishing nonprofit, bookstore, coffee shop and event space geared toward creatives looking for a place to hone their craft. Eclectic works from local artists hang on the walls, while literary magazines, poetry books and novels fill the shelves from the main-level cafe to the poetry room and gathering area upstairs.

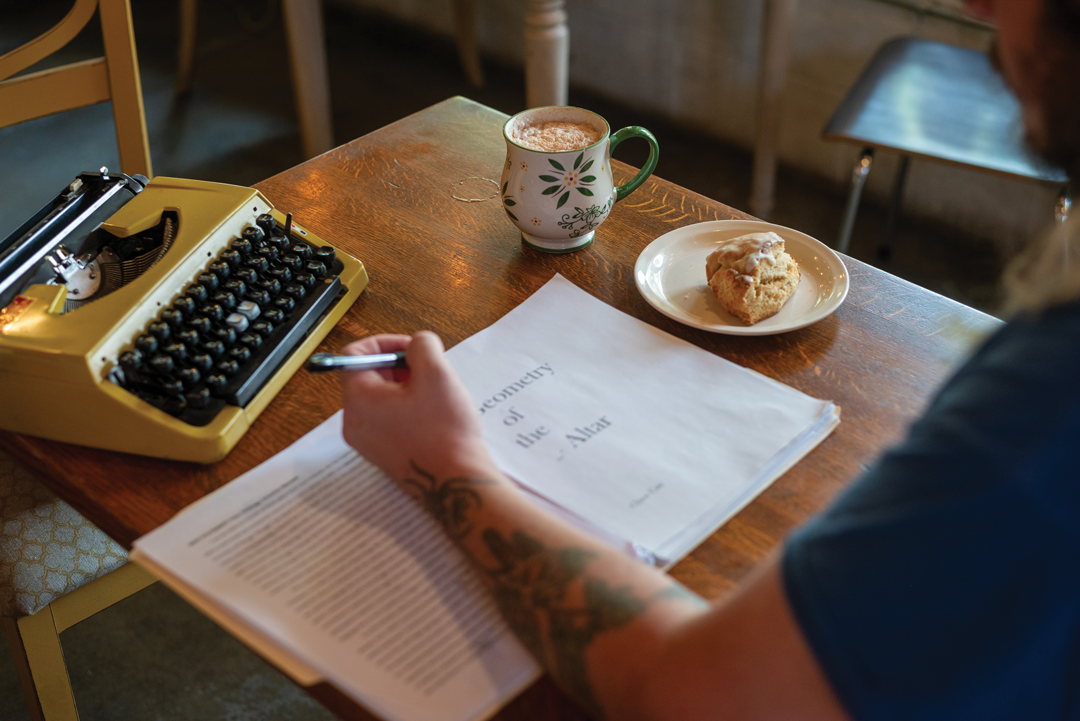

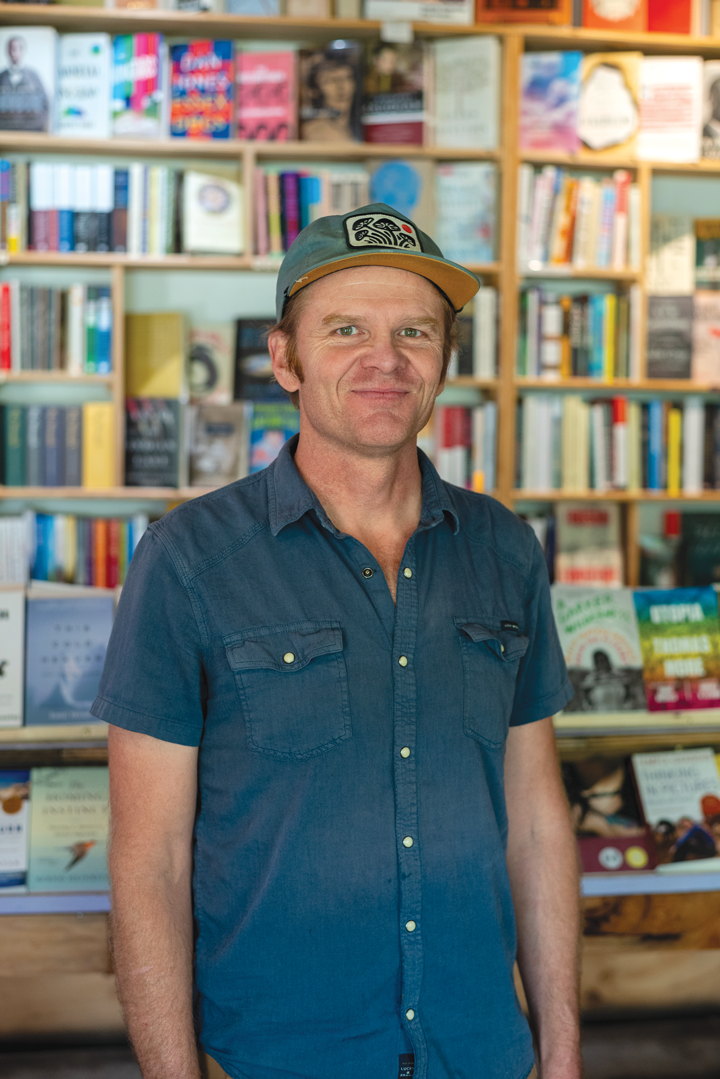

The nonprofit is a culmination of everything founder and director Todd Simmons loves. As a lifelong writer, he’s proud to offer a place for fellow creatives to belong, but the concept wasn’t always housed in a bustling locale. It was born from his imagination more than 20 years ago, when he lived in a yurt in various backyards after jettisoning his career with the National Park Service.

“I was tired of the bureaucracy and a little frustrated with science, and I loved writing books, so I packed my bags and hit the road,” Simmons says. “I started Wolverine Farm Publishing as a way to get that writing out.”

Photos by Jordan Secher.

Humble beginnings

In 2002, Simmons came to Fort Collins from northern Idaho, where wolverines roam free. He liked the idea of bringing more wilderness to the world, though in retrospect, he says it’s the space between the wild (wolverine) and civility (farm) that he was most interested in. At the time, he wasn’t thinking that hard about it.

Simmons wanted to provide an outlet for creative minds like his to publish poems, short stories and other miscellaneous works, so he gathered a few friends and created Matterzine, a publication he fondly refers to as a “chaotic newspaper,” in 2003. Over the next few years, Matterzine evolved into a true literary journal, with writing focused on Northern Colorado. Themes of environmental and social justice were woven throughout each volume.

Each copy only cost $10, but it was enough to keep Wolverine Farm going. Simmons printed 5,000 copies of each volume and worked odd jobs as a ghost writer, substitute teacher, manual laborer and barista to make ends meet while he dedicated himself to the project.

“One [volume] paid for the next,” Simmons says. “It’s always been a pretty bootstrapped type of organization.”

By 2005, he and his crew had published Boneshaker, a series about the philosophies of bicycling. They had also started traveling around the country with New Belgium’s Tour de Fat and secured their first grant from the brewery to convert Wolverine Farm Publishing into a nonprofit.

Simmons then dove into Wolverine Farm full time and opened a volunteer-run bookstore inside Bean Cycle Roasters. He published dozens of works, from new volumes of Boneshaker and the renamed Matter Journal to other writers’ one-off projects and the Fort Collins Courier, the city’s old newspaper.

As more people learned about Simmons’ publishing operation and brought him new ideas, he felt the need to expand the nonprofit into a larger space for activists, writers and artists to come together. That led him to open Wolverine Farm Publick House in 2015 at the place where it stands today.

“People kept coming in wanting to do community-focused things, whether it was around food insecurity or housing issues,” Simmons says. “We saw a hunger for bringing people together and addressing things or expanding on things, so a lot of that work informed the design.”

Todd Simmons

Creative collaboration

The publick house hosts a variety of events upstairs, including community gatherings, poetry readings, workshops, classes and live music. Most of the events are free or donation-based and are open to the public, though anyone can pay to reserve the entire second floor. Groups often do so for presentations, faculty mixers and other private events.

“A lot of what happens here is a reflection of the stuff we believe in and the values we hold dear,” Simmons says. “We are just a mirror of our community. There are a lot of people out there with skills who are trying to find ways to offer them to the world.”

In addition to regular and one-off events, Wolverine Farm runs three-month residence programs for writers, musicians, makers and even readers to help them explore their craft. Residents receive a $150 bar tab and spend a few hours at the publick house every week, then they present a collaborative showcase at the end of the program—the next one is Friday, Oct. 11—which could be anything from interdisciplinary storytelling to a printmaking workshop. Musicians in residence put on one free show every month and earn $50 for each performance.

“It’s a really beautiful thing to watch these creatives develop,” says Chelsea Gilmore, arts and events manager at Wolverine Farm. “These are people who don’t know each other, and we’re asking them to find a common thread within all of their practices. It’s a scary thing to ask people to do, and it’s been amazing to see what people have done.”

The reader in residence program is different from the others in that the focus is on consumption rather than production. It’s a concept Joe Deany-Braun came up with when he joined Wolverine Farm during the pandemic and became the curator of the nonprofit’s bookstore, Perelandra Books.

“The writer is nothing without the reader, so reading has always been a creative act,” says Deany-Braun, who has a master’s degree in creative writing and poetics. “You’re essential to how a work makes meaning, and you’re bringing your own art and attitude to it.”

There is a catch: Readers in residence must read physical books rather than downloading them. But it’s something they embrace, even if many others don’t.

“You’ve just got to stay the course and insist that books belong in physical spaces,” Deany-Braun says. “You don’t have to be a reader to appreciate being around books.”

The Way Cup Program

Wolverine Farm Publick House is currently spearheading The Way Cup, a grant-funded pilot program to reduce single-use cup waste in Fort Collins. Anyone can put a deposit on a cup—it’s a tumbler with a lid and sleeve, so it’s good for both hot and iced drinks—and either keep it or return it later to get the deposit back. Returned cups are washed and redistributed.

“It’s supposed to enlighten and bring to the forefront of conversation the reusable cup versus the disposable cup and how much waste we create, even in our small communities,” says Chelsea Gilmore, arts and events manager at Wolverine Farm.

If the program takes off, The Way Cup will be implemented at other coffee shops and drop-off stations will be available around the city. For more information about The Way Cup and other Wolverine Farm programs, visit wolverinefarm.org.