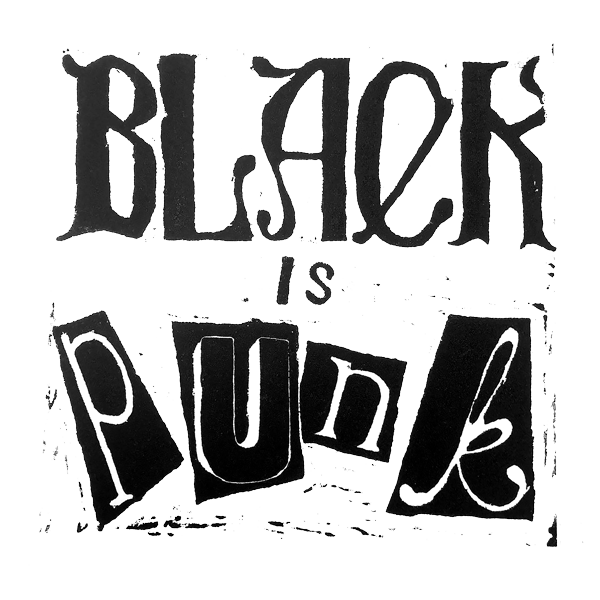

Black is Punk

Nikaiya Lawson never felt like she fit in. Maybe it was her milk chocolate complexion that was a little light to be called Black, but a little dark to be called white. “Just right” is a term reserved for Goldilocks, not skin color. That was the result of her white mother and Black father.

Or maybe—in fact, more likely—it was because Lawson coupled her color with a love for rock and roll, especially the kind that was aggressive, hard and complex. She loved progressive rock, punk and, most of all, metal. This was from her mother, too, and she didn’t think it was weird until confused folks contorted their faces when she told them she loved The Smashing Pumpkins. One of her boyfriends, a white metalhead, once told her he didn’t understand “her” music. When she figured out he was talking about hip-hop, she told him she didn’t understand it either.

“I didn’t feel seen at all,” says Lawson.

Nikaiya Lawson’s art on display during the Black is Punk exhibit.

Not, that is, until she met Ann Adele. Adele liked metal and punk, too, and the two bonded over the progressive rock group, Yes. That’s right: Yes, the super-weird, even nerdy prog-rock band famous for strangely amazing songs such as “Roundabout” in the early 70s before enjoying a resurgence in the 80s with the hit “Owner of a Lonely Heart.”

The two met in a 3D class as freshmen in the visual arts program at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley. Now both seniors, they are still best friends.

“This is like my twin from another universe,” Adele says of Lawson.

Meeting Adele affirmed Lawson’s identity. Finally, Lawson believed she could be herself. But, ironically, meeting Adele also led her to question her identity even more: What did it mean to be Black?

She thought about the many ways Black people might identify themselves. Did it mean all Black people loved hip-hop? Did it mean Adele, with darker skin, was “blacker” than her, and if so, then why did Adele love Yes so much? More importantly, did other Black people feel out of place because they liked, say, Jimi Hendrix instead of Jay-Z?

The result was “Black is Punk,” an art exhibit curated by Lawson and Adele. The exhibit challenged preconceived notions of what it means to be Black while also embracing them. The two collected artwork from Black painters, welders, tattoo artists, hairstylists and braiders, among many others.

The movement is much more outward and outgoing than Lawson and Adele, who are kind and smile a lot, even though they are a bit shy–the kind of personalities wielded by nice people who haven’t felt welcomed for years. But Lawson remains thrilled at the chance to express her thoughts about her individualism.

“I exist, and that makes no sense to you, and I challenge that,” Lawson says. “I like being myself and I like bothering people. Maybe being bothered will help you learn something.”

Ann Adele’s artwork at the Black is Punk exhibit.

More than 150 people attended the opening, and UNC’s Michener Library kept the display open the entire fall semester. People loved it.

“I felt like one of the cool kids for once,” Lawson says.

The reaction they got from it was so good that Lawson now considers Black is Punk a movement, not just an exhibit.

The artists who helped them bring Black is Punk to life have started a collective. They have an art therapist, a graphic artist and Lawson and Adele, who are the two printmaking designers. Their business targets those who care about social issues as well as those who want to invest in local art.

Subscription boxes will present social or local issues critiqued through their artwork, paying tribute to printmaking’s longstanding history of being an art for the people. Printmaking, after all, is how protestors made flyers, signs and other materials to inform the public and right what they considered wrongs.

“We urge the consumer to choose who profits from their attention wisely, by providing resources to jumpstart their own independent research and start investing in culturally relevant artwork produced by marginalized creatives,” their website reads. They call the company Fast at Your Door.

Lawson and Adele have already put forth perhaps the most important idea, a lesson they learned themselves through Black is Punk. Many times, Lawson and Adele were stopped on the UNC campus by students, white or black or brown, who told them the display meant so much to them. It even helped them solidify their identity, they said.

“People want to fit in,” Lawson says. “They just have to find the right world.”

For more, visit sweetleafart.wixsite.com/artwork/team-3