Leon Speth squinted against the sun on an early Saturday morning as he lined up his baked goods and hoped their scents would lead customers to his stand at the Greeley Farmer’s Market.

Leon Speth squinted against the sun on an early Saturday morning as he lined up his baked goods and hoped their scents would lead customers to his stand at the Greeley Farmer’s Market.

Just how early 8:30 a.m. is on a Saturday morning depends a lot on who you talk to, of course, but for Speth, it sure felt early, even with the two young boys he has with wife, Tove, training him to rise with the birds. He’d been up all night baking. That night he planned to grab a luxurious three hours of sleep in between more baking to hock his wares at more markets on Sunday.

It’s a hard life, but Leon is French and German, and baking is in his blood. His father was a chef, and his grandfather was also a baker. He named his stand XLVII’s Bakery after his grandfather’s birth year. The markets give his family a way to make a lot of extra money, and during the pandemic, they were the only way he survived: His main gig, providing pretzels to breweries, shut down during the worst of COVID-19. He hits 10 markets a week, and he’s grateful to them for giving his Thornton family a good life despite the grind. Two hours later, it was easy to see why: a line of a dozen people eagerly waited for his French pastries and giant German pretzels.

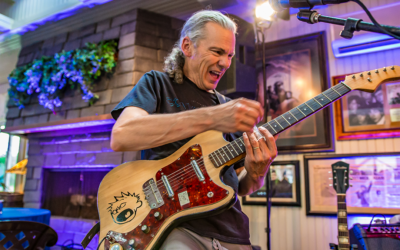

“This is a baker’s life,” Leon says while his sons Enzo, 3, and Valentino, 2, danced to live music played by David G. Smith. “But we are doing really well. This is probably only possible in America.”

The Speths are an extreme example, but farmers markets and their continuing popularity have been a boon to small businesses across Northern Colorado. Many say that without them, they wouldn’t be in business at all. Even those who don’t make bushels of money at the markets enjoy the same advertising that a storefront provides, possibly more.

Redemption Road Coffee, out of Mead, came to Greeley’s market to advertise as much as sell.

“We wanted to tell our story in person,” says Jessica Harsch, who owns the business with her husband, Aaron. “Meeting people and having them taste our coffee was the most pivotal thing. That’s what allowed us to thrive. It would be impossible to advertise like that anywhere else.”

Mrs. Glover’s Goods joined Greeley’s farmers market last year in the mid-season selling elderberry syrup, which Taylor Glover of Keenesburg markets as a delicious health and wellness product. Glover, a stay-at-home mom of two, started her business in January 2019.

Most of her online business came from Florida before she began selling at Greeley’s market. The response was so good that she’s hiring staff and attending several markets a week. Now most of her business comes from Colorado.

“Each year I’ve gotten bigger,” Glover says, “and going to the farmers market is what will set me over the top.”

Beyond the business it brought, Glover appreciates the small-town feel of the markets and their sense of community, even among the technically competing stands. The owners of Illuman Apiary, for instance, ran XLVII’s for an hour or so on a recent weekend while Leon left during a minor emergency.

“I feel like—this sounds corny—but this is somewhere I belong,” Glover says. “These are my people. It’s how I like to live my life.”

Kinda wholesome

The Fort Collins Farmers Market began in 1984, a time when agriculture seemed to be in danger and farmers were looking for another way to market their products. The markets also gave residents an easy—and fun—way to support local farmers while learning about how they grow their products.

The Fort Collins Farmers Market began in 1984, a time when agriculture seemed to be in danger and farmers were looking for another way to market their products. The markets also gave residents an easy—and fun—way to support local farmers while learning about how they grow their products.

“We were really the only one around,” says Barbie Lytle, the treasurer of the Colorado Agricultural Marketing Cooperative.

Indeed, Lytle says the market is the oldest one run by a farmers’ co-op in the state. The cooperative runs three markets Sunday and Wednesday in Fort Collins from May to mid-November. They try to keep it to producers from Northern Colorado, though they do have some from other parts of Colorado and a couple from Wyoming.

“Now people are very interested in knowing where their food comes from and how fresh it is and how it’s handled and picked,” Lytle says. “In this day and age that’s very important.”

Farmers markets have even been a lifesaver to places referred to as “food deserts” that aren’t served by nearby grocery stores where they can buy fresh vegetables or fruits. That was downtown and east Greeley for many years before a Natural Grocers opened a few months ago.

All this sounds wholesome, in an age when wholesome is a rare commodity, especially when it comes to food. But, yep, there’s a catch. Farmers markets vary in what’s offered and who offers it, and some of them tend to look more like flea markets. The Fort Collins Farmers Market offers “value-added foods,” Lytle says, emphasizing produce and welcoming products such as sauces and some baked goods. This definition is open to debate, of course, as the market does offer homemade soap and a few other products you can’t eat, even in a pinch. But Lytle has boundaries.

“We don’t do art and jewelry,” Lytle says.Others do, and they tend to be private farmers markets that charge a hefty fee for booths, Lytle says. The Fort Collins market has avoided those fees because it sits in a parking lot owned by the Don and May Wilkins Charitable Trust of Fort Collins, which stipulated that part of the land had to be designated for agriculture.

“These private markets charge a fee and that’s their goal,” Lytle says. “They have large rents to pay. We are fortunate.”

A community service

Still, many of the more popular and common markets are backed by a city, county or university.

“It’s not a money-maker for the city,” says Andrea Haring, special events coordinator for the City of Greeley, who runs the market. “It’s about providing a community service.”

Because of this, Haring isn’t interested in packing the market with a bunch of bakers, a product that became even more common after the pandemic as people turned to their kitchens for comfort.

“I want it to be a well-rounded market,” she says. “I don’t want to create too much competition among them. I want it to work for them.”

Haring also gives preferences to established vendors in good standing and gives discounts if they commit to the whole season. Markets naturally tend to fluctuate with the seasons, but Haring doesn’t want her market to die when crops are harvested. In early June, the market was a bit slow, but it will grow, she says without a smirk, and be blooming by near the end of summer, when peaches and other popular items such as chili roasting hit. She does have drop-ins, and the market changes throughout the year, but many are consistent.

“An empty market is a bad market,” she says and charges fees to vendors who simply don’t show up.

The application process and food regulations tend to weed out sketchy start-up businesses who think they will make a quick buck by selling their backyard gardens. She also allows a space for a different nonprofit every week.

“I have very few non-food vendors,” she says. “I want to maintain the integrity of it being a farmers market.”

Loveland’s city farmers markets allow an artist market on the last Sunday of every month and has some vendors come and go. Unique products are the best as long as they fit the market. Probably 99 percent of the vendors are from Northern Colorado.

“We are always looking for vendors who have a produce item that isn’t sold by someone else,” says Kerry Helke, senior recreation coordinator for special events for the City of Loveland. “Only so many things grow here and grow well.”

The city’s farmers markets are designed to offer opportunities to vendors who couldn’t afford the huge markets, but the glut of markets have created healthy competition among them to get the best vendors. A green chili vendor who roasts on site, for instance, brings in big crowds and then everyone is happy.

The city’s farmers markets are designed to offer opportunities to vendors who couldn’t afford the huge markets, but the glut of markets have created healthy competition among them to get the best vendors. A green chili vendor who roasts on site, for instance, brings in big crowds and then everyone is happy.

“Markets are this new trendy thing in the last five years,” Helke says, “But it’s really competitive now. In order to have a good market, you have to have good vendors, and they can only be in so many places. There are a lot of markets that try to get off the ground, but if you don’t have good vendors, no one comes.”

The old saying that a rising tide lifts all boats still tends to be true among the markets, however, as vendors credit them for giving their business a big boost. Stephanie Baudhuin, the owner of Colorado Crummies, came to Greeley’s market in 2019 as a test. She was a graphic artist who gave up eating commercialized meat in 2017. She and her husband missed it only on Tuesdays because, you know, taco Tuesdays. They created a crumble recipe out of veggies that she says is as versatile and tasty as ground meat.

“I didn’t know quite what I had,” Baudhuin says, when she started selling at Greeley’s market. “I didn’t even consider myself an entrepreneur. It was a big learning curve for me. But you were around a bunch of small business owners, so the camaraderie was amazing.

“You get a lot of feedback from customers sampling your product, looking at their faces when they try it.”

She hopes her own market in Milliken offers other vendors the same boost she got when she entered the market herself.

“I learned so much from other food businesses,” she says. “I don’t think I would have had the confidence or the skills to keep going otherwise.”