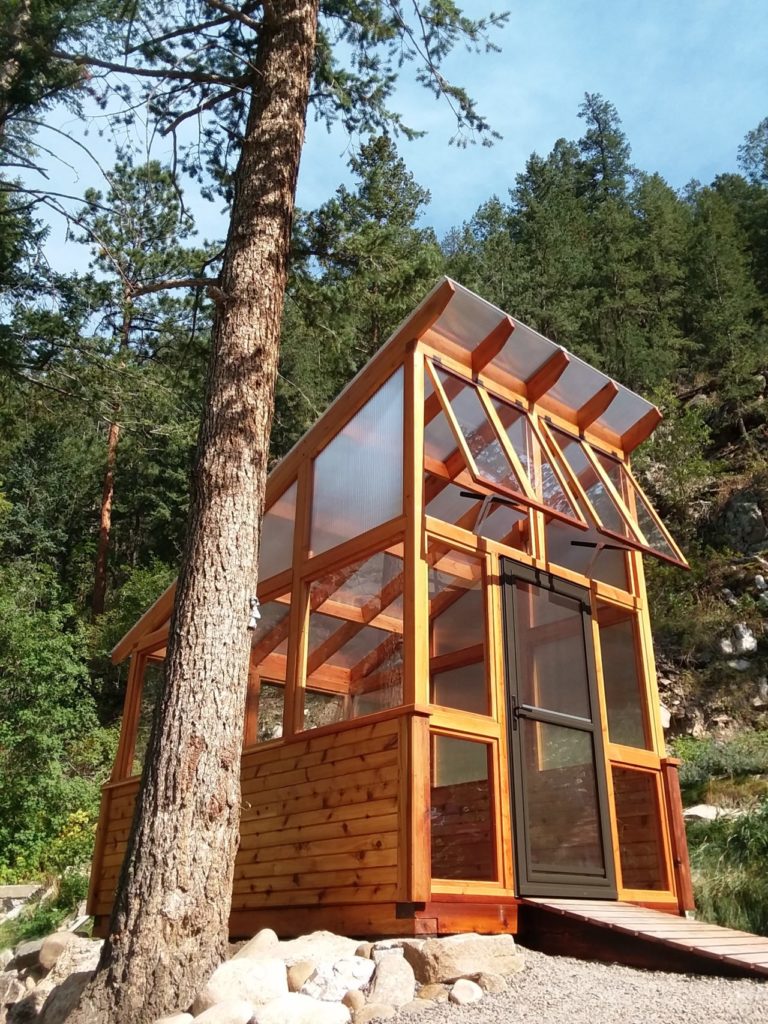

Photos courtesy of Sunspot Greenhouse Company

The birds are chirping again, signaling spring’s arrival and making us eager to get out in the garden. But we still have a few frosts left before it’s safe to transfer those tender veggie shoots into our raised beds, so we’ll have to hang tight just a little bit longer.

Unless you have a backyard greenhouse, that is.

Heated greenhouses provide a year-round solution to our short growing season, says Dr. Josh Craver, assistant professor of controlled environment horticulture at Colorado State University. Unheated greenhouses only allow us to extend it by a few weeks in the spring and fall. Ultimately, it comes down to how much control you want to have over your growing environment during the colder months.

Detached four season greenhouse with monoslope roof.

“Maybe you just want to start seeds early in the season so you’re ready to transfer them into your garden mid-May, and an unheated greenhouse will help you accomplish that,” he says. “If you’re looking to grow tropicals and have a nice botanical area in the winter, you’ll definitely need the extra protection of a heated greenhouse.”

A lot goes into choosing the right type of greenhouse, especially if you’re building one yourself. Three-season greenhouses are unheated and cheaper overall but drop below freezing in the winter. Four-season greenhouses get their heat from electric, gas or capturing the warmth of the sun with expensive, high-grade insulation.

James Connell, owner of Sunspot Greenhouse Company in Fort Collins, offers custom-built greenhouses and a variety of kits for people to DIY the right way.

“The most common mistake people make when building any type of greenhouse is buying PVC and cheap plastic tarps from the hardware store,” says Connell. “Using the right materials is incredibly important—you need a strong, durable frame and greenhouse plastic that is stabilized against UV damage for it to really last. A well-built greenhouse is a lifetime product, and you’ll only need to replace the cover every 10-20 years.”

According to Connell, there are five key components to a greenhouse: the foundation, the frame, the cover (or glazing), ventilation and heating. First is the foundation, which can be complex and expensive or simple and affordable. Concrete is the priciest option, with two-and-a-half foot deep edges or piers augured several feet into the ground. Cheaper foundations consist of wood beams pinned to the ground with rebar, or a few inches of gravel with the greenhouse secured on top.

Then comes the frame, which can be made of wood or metal as long as it holds up to high wind and snow loads. Connell says geodesic domes make the ideal greenhouse frame due to their strength and shape: “Geodesic domes use the least amount of building material for the volume of space they create, and they distribute wind and snow loads more evenly across the whole structure rather than just the top. Since geodesic domes have a lot of sides, you’ll also get direct sunlight no matter where the sun is positioned in the sky, which results in better trapping of heat.”

- Attached greenhouse interior with raised beds and potting benches.

- Paver floor

- Ventilation windows

The type of glazing also determines how much heat is trapped due to its insulation value. Flexible, tarp-like glazing is made of UV-treated polyethylene but provides little insulation, making it an appropriate choice for high tunnels and three-season greenhouses. Rigid plastic offers more insulation, with hollow polycarbonate panels that trap warm air and provide more passive heating for four-season greenhouses.

When it comes to glass, Connell and Craver say proceed with caution. Glass is beautiful and long-lasting, but Northern Colorado’s summer hailstorms will smash right through it. It also has a low insulation value, so you’ll need additional heat in winter if you use it to cover a four-season greenhouse.

There are plenty of heating options. Passive greenhouse designs are the costliest upfront because of the insulation, but they will greatly reduce your utility bills (and carbon footprint) over time thanks to the free solar heat. Alternatively, electric or gas heaters are initially cheaper but cost money every month.

Detached three season gothic arch greenhouse.

Trapping heat may be important in the winter, but it can be a recipe for disaster in July and August. Connell says unventilated greenhouses can exceed 120 degrees in the summer and kill your plants. He recommends top-hinge awning windows operated by automatic, non-electric openers so you don’t have to manually adjust your vents every few hours.

But the right growing environment for your seedlings, tropicals and other non-hardy plants, ultimately depends on light.

“Even if you have all the other components right, if you don’t have enough light, that defeats the purpose of having a greenhouse,” says Craver. “Where you place a greenhouse has a huge impact on how much light you get, so decide where you want it before you even start building. Ideally, you’ll want to put it on the south side of the house and orient it east to west so you’re capturing as much daylight as possible—and don’t forget to think about trees, your neighbor’s house and anything else that could cast unwanted shadows.”