Alexa and Brock Maxey stared in shock at the dirty mess where their grass used to grow, and they had one thought: What would the neighbors think?

They lived down the street in the Mountain Shadows subdivision in Greeley from neighbors who treated their lawns like they expected the Rockies to play on it. But the Maxeys, both in their mid-40s, hated their yard. Their house faces south, and the sun beat down on the grass as soon as the birds began chirping. By the hot summer, it was as crunchy as a midnight snack. They never spent time outside. Next year, Alexa told her husband, she was going to tear it all out. Brock didn’t believe her.

But she’d committed to a program run by the City of Greeley that encouraged xeriscaping. Alexa heard about it many times at her job since she worked for the city. Northern Colorado cities have tried for decades to battle the stigmas of xeriscaping and encourage residents to save water, a tactic that takes on even more urgency as our weather gets drier and more people move to Northern Colorado.

“I don’t think we can continue installing bluegrass the way we have in the past 50 years,” says Ruth Quade, the head of water conservation for the City of Greeley. “We aren’t in Kentucky.”

But three things held Alexa back: She was nervous, their green-thumb neighbors and the fact that she’d never planted anything in her life.

“I knew NOTHING about plants,” Alexa says.

They decided to give it a shot. They got somehelp from the city’s Water Conservation Program, watched a virtual seminar put on by the Denver Botanical Gardens and began asking around for help. They wondered during their shopping trips if they should just hire the person explaining, say, how to plant a tree. They read about plants and what went with what. They began to follow landscaping maps to figure out what to pick. They walked barefoot on some Dog Tuff grass because, yes, turf was a part of xeriscaping, just not the whole yard and just not the kind that’s as thirsty as bluegrass. Brock dug so many holes that by the end of last summer, he could dig them in a quarter of the time.

They discovered plants that smelled like chocolate, ones described in the Bible and some that looked like red birds. They used some rock for a dry riverbed, but not nearly as much as they initially thought they would, or as much as their neighbors thought when they came by to ask about their plans.

By the time they finished, theyfound spending so many hours in the yard helped alleviate the stress brought on by the pandemic, even after both continued working. They began to have picnics out in the front yard. They met many of their neighbors walking by at night who stopped to ask about how they learned how to do all that, including the ones with the manicured lawns.

“We started enjoying it,” Alexa says. And though they had doubts, they are glad they didn’t just hire someone to do it.

“We did it ourselves,” Brock says. “That’s what made it fun.”

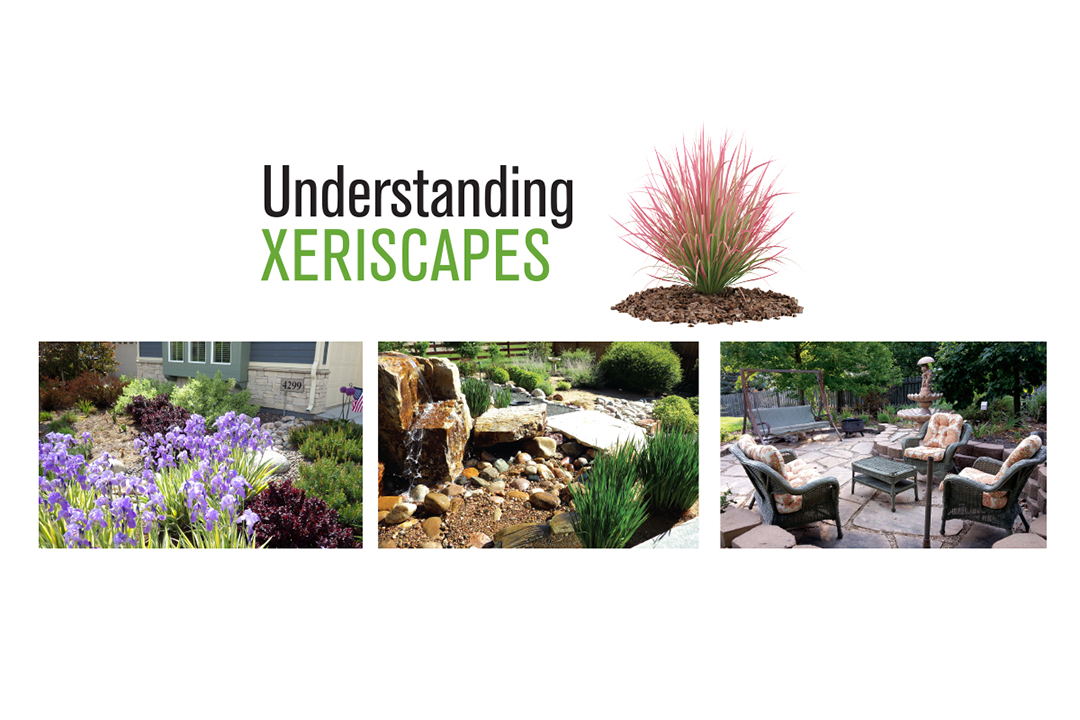

It’s not what you think it is

Whenever Stephanie Selig, the owner of Sundrops and Starflowers in Loveland and Fort Collins, finds herself with a new customer, she first finds herself clearing up a couple misconceptions.

“I say, ‘it’s not ZEROscaping,’” Selig says.

Xeriscaping’s been around longer than you think, but many still think xeriscaping means tearing up grass and throwing down a bunch of rock in its place. Selig, who is also an active member of the Associated Landscape Contractors of Colorado, works mostly with do-it-yourself homeowners such as the Maxeys. Most are pleasantly surprised at all the options they have to dress up their yard and make it more water efficient.

“We don’t want you to take out your plant material,” Selig says. “The plant material is helping us lower the temperature of our planet. We need our trees desperately. Let’s work really hard to keep them.”

Jack Fetig, the owner of Fossil Creek Nursery and Alpine Gardens in Fort Collins, who lives on the north edge of Loveland, discovered xeriscaping in the 1980s, when the Denver Water Board began to talk about it as a way to save water (the board, in fact, coined the term in 1981). Back then, with growth at a standstill and climate change much less of a threat than the USSR roasting us with nuclear weapons, water seemed like a plentiful resource, but those board members knew better.

“There were some forward-thinking people,” Fetig says. “They said water was going to be an issue, and so maybe we should change the way we landscape, since that what was using all the water.”

Fetig and his wife started a landscapebusiness back in 1978, and even then, they knew water would affect their business.

“But really, xeriscaping was about common sense things that make for a much nicer and easier landscape that fits our area more,” he says.

These days Fetig will do what thecustomer wants, but he tries to steer them toward xeriscaping, and he tries not to mention fields of rock when he sells it. Landscaping gets better with time, but rock, he says, will never look better than the first day it’s installed.

Modern landscaping, not xeriscaping

Northern Colorado’s climate was never going to be a rainforest. Nathan Meeker was considered an expert in agriculture when he wrote for The New York Tribune, but even he struggled with the arid climate and rock-hard ground when he moved a group to Colorado in 1870 to start Union Colony, which he named Greeley, after his newspaper editor and financier. That climate remains today—it’s probably even drier now—and yard designs should respect it, Fetig says.

Northern Colorado’s climate was never going to be a rainforest. Nathan Meeker was considered an expert in agriculture when he wrote for The New York Tribune, but even he struggled with the arid climate and rock-hard ground when he moved a group to Colorado in 1870 to start Union Colony, which he named Greeley, after his newspaper editor and financier. That climate remains today—it’s probably even drier now—and yard designs should respect it, Fetig says.

One of the more common aspects of xeriscaping divides a piece of land into zones and directs plant choices to match them. Zones can be as simple as “hot and dry,” “cool and wet” and “something in between.” These zones, believe it or not, can all exist in one small yard.

“On the hot side of the house, you might use plants that are more drought tolerant,” he says. “That doesn’t mean you can’t have wet plants. It means you put them in the right spots.”

That also doesn’t mean tearing out all the turf. If you have dogs and kids who like to play in the backyard, a piece of turf, even bluegrass, may be appropriate. Bluegrass is a good turf. It just doesn’t make sense to cover a whole yard with the thirsty grass in an area where water is scarce. “You need to use it properly,” Fetig says, “and not as just a cheap cover.”

As more subdivisions take up open spaces that used to act as habitat for local animals, landscaping can help soften the blow by providing that same kind of habitat, Quade says. That’s what makes a variety of plants, trees and flowers important as well as fun and more interesting. Those plants will require fewer pesticides and fertilizer as well as less water. “There’s lots of benefits behind it,” she says.

It may seem like a lot of work, Selig says, and it can be, especially at first, but once everything is in the ground, it doesn’t have to take up weekends.

“It really depends on what you call maintenance,” she says. “If you think mowing isn’t a lot of maintenance, then you won’t be disappointed. If you are paying the neighborhood kids twice a week to mow it and never pay attention to your yard, then yeah, there’s more maintenance. It’s really what are you willing to do.”

Everyone, even the industry, needs education

Given that most homeowners don’t know much, if anything, about landscaping and yet still cling to misconceptions about xeriscaping, education seems to be the most important component to getting more to embrace it. That’s what Quade, Fetig and Selig say is the key.

Given that most homeowners don’t know much, if anything, about landscaping and yet still cling to misconceptions about xeriscaping, education seems to be the most important component to getting more to embrace it. That’s what Quade, Fetig and Selig say is the key.

And yet, practically everyone can have the title “landscaper,” making it difficult to match homeowners with knowledgeable designers. “The barrier to entry is very low,” Selig says. “A guy with a shovel is in the landscaping business if that’s what he wants.”

Part of the Associated Landscape Contractors of Colorado’s job as an organization is to lobby for its business owners, and Selig talks to legislators about establishing stricter guidelines for a landscaping license. The ALCC is rolling out a certification program in sustainable landscape management to establish its own standards if the state legislature doesn’t want to bother. In the meantime, homeowners can protect themselves, especially if they want to look into xeriscaping.

“Clients should ask landscaping companies about their certifications,” Selig says. “That’s not a bad question.”

Quade says there still are many landscapers who don’t practice xeriscaping or don’t really understand the concepts of it. “Greeley is still catching up with the concepts,” she says, even with her years of marketing and instruction, backed by a city that’s valued conserving water for decades.

Fetig does believe homeowners understand that saving water is important. Many, for instance, do follow guidelines for watering, even if they’re still watering thirsty lawns. Fetig still tries to steer customers to xeriscaping. “It’s easier now with smaller yards,” he says. “It really is. Utilities are raising the price of water, and I think that’s helping make people more and more aware.”

Maybe so, but Selig, whose business centers on homeowners who take on projects themselves, believes homeowners could do more.

“They don’t even understand how their sprinkler timer works,” she says. “They could save a lot of money and water just by learning how to manage that. A lot of people turn it on in May and never change it. That doesn’t really work.”

As for those initial concerns about their neighbors looking down on them, the same concerns the Maxeys had before they tore up their lawn, Selig believes those are exaggerated.

“Honestly neighbors just want you to take care of your yard,” Selig says, “and that’s all they really want.”

Xeriscapes in Seven Steps

Xeriscaping is a system, not a catch-all phrase for using less water on your garden. Here are the seven steps to the system:

- Plan and design. Look at how water drains on your property, and where the shade falls and at what times of the day. What areas get the most traffic and who delivers it, such as kids, dogs or adults with beers. Your plants should reflect those zones.

- Evaluate and improve soil. Soil can be improved with organic matter such as compost.

- Create practical areas. Turf is still important in areas with lots of traffic. Turf doesn’t have to be bluegrass.

- Use plants. Choose plants to fit your microclimates, with an emphasis (but not a limitation) on native plants suited for our area, and group them by watering needs.

- Water efficiently. Develop a proper sprinkler system or hand-water some areas.

- Mulch. Use mulch to slow weed growth, reduce evaporation and add some beauty.

- Maintain your yard. It is as simple as that.

Source: Green Industries of Colorado. Visit to watersmartplants.com/gre for some plant ideas.

Dan England is a freelance writer who lives in Greeley. To comment on this article,emailletters@nocostyle.com.