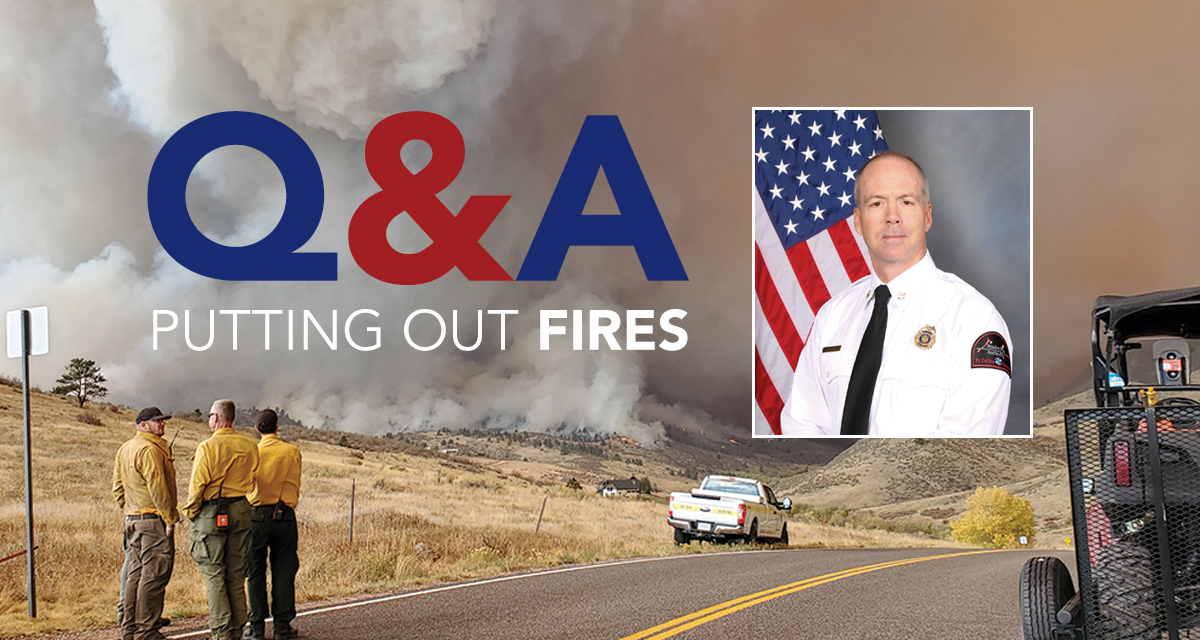

The Cameron Peak Fire ignited on August 13, burning 209,000 acres, destroying over 460 structures and taking the ignominious title of Colorado’s largest wildfire in history. Poudre Fire Authority (PFA) began battling the fire immediately as an interagency partner, even as Cameron Peak Fire crept into our own backyard in mid-October. Though he is quick to tell you that there were many firefighters who spent more days on the front lines than he did, Special Operations Battalion Chief Geoff Butler has had the responsibility of managing PFA’s response to the Cameron Peak Fire. He shares a little of his experience.

Q: Tell us about yourself and your career with Poudre Fire Authority.

A: During my 20s, I worked as a mountaineering/climbing guide. I then worked in wildland fire for three years and was hired by PFA in 1998. I became a captain in 2011 and battalion chief in 2017. During my time as captain, I spent three years as the Wildland Fire Program Manager. In February 2020, I transitioned from my role as an online battalion chief to the position of Special Operations Battalion Chief, where I supervise the wildland fire, technical rescue, HazMat and drone programs. I hold a bachelor’s in political science, a master’s in forestry (wildland

fire management), and a master’s in public administration (with a graduate certificate in emergency management).

My wife of 18 years is Jane Gordon. We met through rock climbing (she was a climbing ranger and I was a climbing guide in Rocky Mountain National Park). She now works for the U.S. Forest Service as a Special Uses Permit Administrator after 20 years of working in law enforcement and fire. My son, Peter, is 17 years old, attends Rocky as a junior and is into music. My daughter, Madeleine, is 15 and a sophomore at Rocky. She is into the outdoors (especially mountain biking and skiing) and is a gifted artist. There is also a cat that lives in our house.

Q: Tell us about your responsibilities with regards to wildfires.

A: I oversee the PFA wildland fire program. In addition to our standard engines and ladder trucks (for structure fires), we have nine wildland fire engines, six of which are cross staffed at career stations and three are housed at our two volunteer stations. We have an out-of-district wildland team that responds to large fires throughout the U.S. This provides our firefighters with experience that our organization can then rely upon during local incidents, such as the Cameron Peak Fire. As part of that team, I personally deploy as a taskforce leader (as do several other members of our team) or division supervisor.

Q: What about Cameron Peak Fire made it grow so fast and aggressively?

A: Seasonal drought (summertime) plus episodic drought (a dry summer) plus mountain pine beetle mortality in lodgepole pine plus many breezy days and several wind events. Lodgepole pine (the predominant forest type where the Cameron Peak Fire began) has a fire return interval [average period between two successive fires in a designated area] of 175 to 300 or 400 years. This forest type has evolved to regenerate after stand-replacing events (the old forest needs to be wiped out for the next generation). In other words, lodgepole pine tends to grow into crowded stands, which eventually become stressed by drought or pathogens (or both), making it susceptible to stand-replacing fire. As lodgepole is not shade tolerant (needs sunlight to germinate and grow) and its serotinous cones are designed to open when the fire’s heat melts the coating of pitch, it relies on the fire cycle for regeneration.

Q: The Cameron Peak Fire raged for almost three months. What was it like for your team to battle a fire for that long, knowing you could not prevent the loss of structures along the way?

A: This fire burned predominantly in other jurisdictions. It wasn’t until October 14 that it began to directly threaten our jurisdiction. During this fire, a host of local and national resources took two and three week turns fighting this fire.

While this level of nationwide interagency cooperation is typical, it is hard to really appreciate until one has been a part of it. PFA responded with on-duty crews as part of the initial attack on day one, followed by sending leadership and engines on two-week deployments, supplemented by “surge” resources on particularly active days. These surge resources served on multiagency taskforces as well as PFA-only taskforces once it got close to our jurisdiction. During this time, we were able to rotate crews and still provide our regular service to our community. While by no means overwhelming to our organization, this incident required the support of everyone in the organization. I think I summarized it well in an email I recently sent to the department. It read as follows:

“As you know, the Cameron Peak Fire is the largest (and has to be one of the longest) wildfire in recorded state history. We have been involved since the initial attack on 8/13 and throughout its 200,000+ acre/40-mile run. On 10/17 the fire moved into our district, destroying several houses and displacing a large portion of the citizenry we serve. Despite the losses, I have no doubt that the firefighting efforts of our personnel played a direct role in saving numerous homes and perhaps several lives. Each one of us has played an important role in dealing with the incident…. Special recognition is extended to our volunteers and career firefighters who were personally impacted by the incident and continued to perform their duties in the service to their neighbors and the community at large…. My pride in this organization and appreciation for each of you has never been higher, a widely held sentiment I am sure.”

Q: Give us an idea of what fighting Cameron Peak Fire was like on a daily basis.

A: I would not presume to present my experiences as widely representing the experiences of the thousands of firefighters who have been assigned to the Cameron Peak Fire. Additionally, this fire burned for three months across 200,000 acres and 40 miles. As such, the weather, fire behavior, terrain, elevation, vegetation and personnel were quite diverse and continuously changing. In other words, I can’t describe a typical day but will give some examples.

During my initial two-week deployment, I got up before 0600 and usually hit the sack around 2300. Due to COVID, there was no large base camp and logistical support was a little more do-it-yourself than usual (which was actually just fine with me). The day started with packing up my campsite and retrieving breakfasts and lunches for my crews (typically, around five engines and a 20-person hand crew).

We would then listen to a morning briefing from the incident management team delivered over the radio. This was followed by meeting my crews, distributing meals and then another briefing with the division supervisor, other taskforce leaders and the crew bosses to line everyone out on the day’s tactical plan and assignments.

The daily work varied, but could involve fire line construction and burnout operations, structure protection close to the fire, structure preparation (assessing structures, thinning around them, setting up sprinklers, etc.), scouting in new areas and tactical options. By around 2100, it was back to the forward operating base to pick up and distribute dinner to the crews followed by some obligatory daily paperwork. Then, set up camp (usually just throwing my sleeping bag on the ground) and sleep.

Q: How were coordination efforts with firefighters from across the nation? Is there a sense of brotherhood in these situations?

A: There is an extraordinary level of interagency cooperation that goes into managing these incidents. We rely on responders from across the nation who work for federal, state, local and private entities. We are fortunate to work for a fire department that supports us in providing the same sort of assistance when other communities are in need. I continue to be impressed by the dedication and

professionalism of the local U.S. Forest Service district, Larimer County, Colorado State Division of Prevention and Control and the myriad of local cooperators.

In addition to the outstanding service and dedication provided by career firefighters, we should acknowledge the service of the PFA volunteer firefighters (we have two volunteer stations, at the south end of Horsetooth Reservoir and Redstone Canyon) as well as the volunteer fire departments throughout Larimer County (Red Feather, Glacier View, Livermore, Estes Park, Loveland Rural, Poudre Canyon). Many of these folks remained on the fire line as their homes and those of their neighbors were threatened or worse.

We should also recognize the hardship endured and patience, understanding and grace exercised by our citizens who were displaced or otherwise impacted by this

large and prolonged incident. I can only imagine the challenges they faced. Their support has been tremendous.

Finally, I would like to thank those citizens who complied with evacuation orders and those who were proactive in creating defensible space around their homes. This makes the work of firefighters much safer and more efficient.

Q: What is the PFA predicting for Summer 2021?

A: Only fools and tourists predict the weather.

(Editor’s note: In our January magazine, we will be featuring an article by Dan England on the impacts of the Cameron Peak Fire on our local forest, water quality and more.)