All information in this article is current as of press time.

The biggest school districts in Windsor, Greeley, Loveland and Fort Collins all have their own plans for school this fall. They look different, and yet, there’s one thing officials agree on: This fall won’t look like last spring.

“We can’t do it the way we did it in the spring,” Todd Lambert, assistant superintendent for the Poudre School District (PSD), said during a presentation to the school board in June. “You and I agree on that.”

Local school districts are proud of their teachers and the effort it took to go virtual on what was effectively a week or two of notice. But they also acknowledge many of their students suffered as a result.

Across the state, districts reported engagement numbers of 50 percent or less, meaning many students didn’t even bother to sign on, and yet districts hesitated to fail them or even dock them a grade, as everyone acknowledged it was also a crappy time.

Now, however, there are fears that students will fall behind a year if things continue the way they were in the spring. Officials in the four major Northern Colorado school districts listed above didn’t have entire or explicit details mapped out for the new school year at the end of June. A second wave of the virus was already emerging in many states, with some reporting daily increases higher than even the first outbreak. Yet Colorado, so far, had bucked the trend. This left district officials optimistic but still planning for a number of scenarios.

“It’s overwhelming just thinking about how much there is to do,” says Theresa Myers, director of communications for Greeley-Evans School District 6, “and yet this evolves—and I’m not joking—every day.”

But we did find some common ideas, philosophies and plans that shouldn’t change much, if at all, once school districts welcome your kids back this fall. And we also found that other school districts not listed here are following the same philosophies, even if they have different ways of planning for it.

Parents want their kids back in school, and so do the districts

Officials from the Thompson School District in Loveland were working on bringing 100 percent of their students back for the fall in late June, despite saying they didn’t think that would be possible in early June. The philosophy probably comes from a strong desire to see students again as much as anything else.

“We know relationships matter for our students, and the best way we can help them is to get them in a class with their teachers and peers,” says Dawne Huckaby, chief academic officer for Thompson. “Online is our last recourse. We need to get our staff back together.”

Most parents, as many as 90 percent in some districts, said they wanted their kids back in school in some capacity, and most of those parents preferred it to be full time. In Greeley, for instance, out of more than 3,700 responses, nearly 2,300 said a full day of in-person learning was their first choice, according to Myers. “We are committed to bringing kids back to class,” Myers says. “We absolutely want kids back in school.”

Teachers and staff struggled nearly as much as the students with the virtual system, Lambert adds. “We got into this profession to see our kids and build relationships and do the work with them. We have also heard from dozens of families that they want their kids in school. We do, too.”

Even officials from Weld RE-4 School District in Windsor, which preferred to wait until late July before releasing anything more than a skeleton plan because of all the uncertainties, said they preferred a modified traditional model with students attending daily classes at school with additional safety measures.

“We will absolutely be back to a traditional schedule if that is permitted,” says Lisa Relou, spokeswoman for RE-4. “The other hybrid models are just contingencies if that is not allowed.”

But the districts won’t be caught off guard this fall

Those hybrid models Relou spoke about were common among all the districts; they are all determined to be ready to switch to virtual learning, or a combination of virtual and online learning, on a day’s notice.

RE-4 spent some of the federal school emergency money all districts received on professional development to prepare them for offering much more robust virtual learning and holding students to high standards.

“We have an obligation to provide students with the type of high-quality education our community expects,” Relou says. “So, we are working really hard to do that no matter what type of environment we will be in.”

RE-4, like many other school districts, would hope for students attending school on alternating days and taking virtual classes on the other days if any virtual instruction was required.

PSD, in fact, already plans to have a hybrid system at the start of the year, with students attending a full day of classes two days a week and at home two other days a week. The district will give teachers a day to plan and collaborate on Friday while students take some sort of virtual instruction. Officials said they would hope to be back to a traditional schedule after winter break.

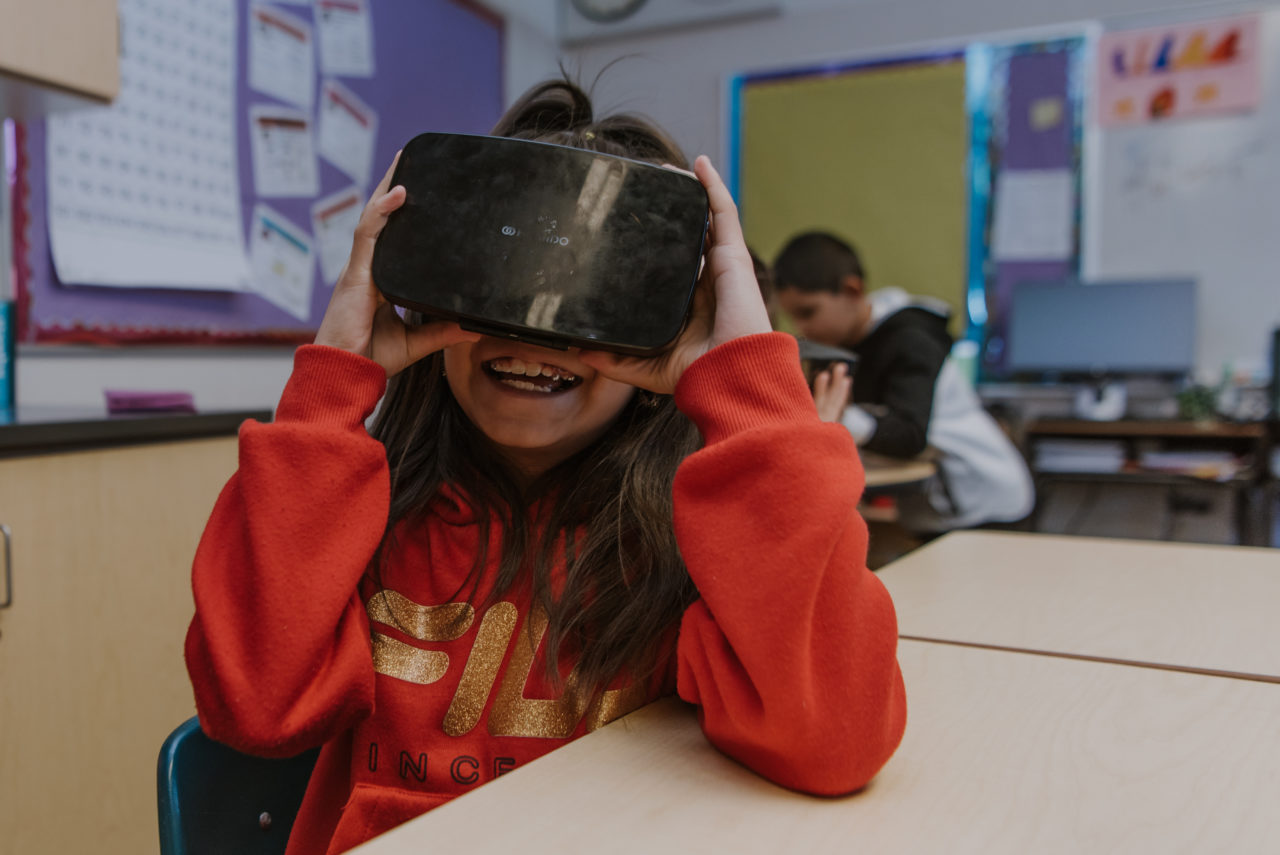

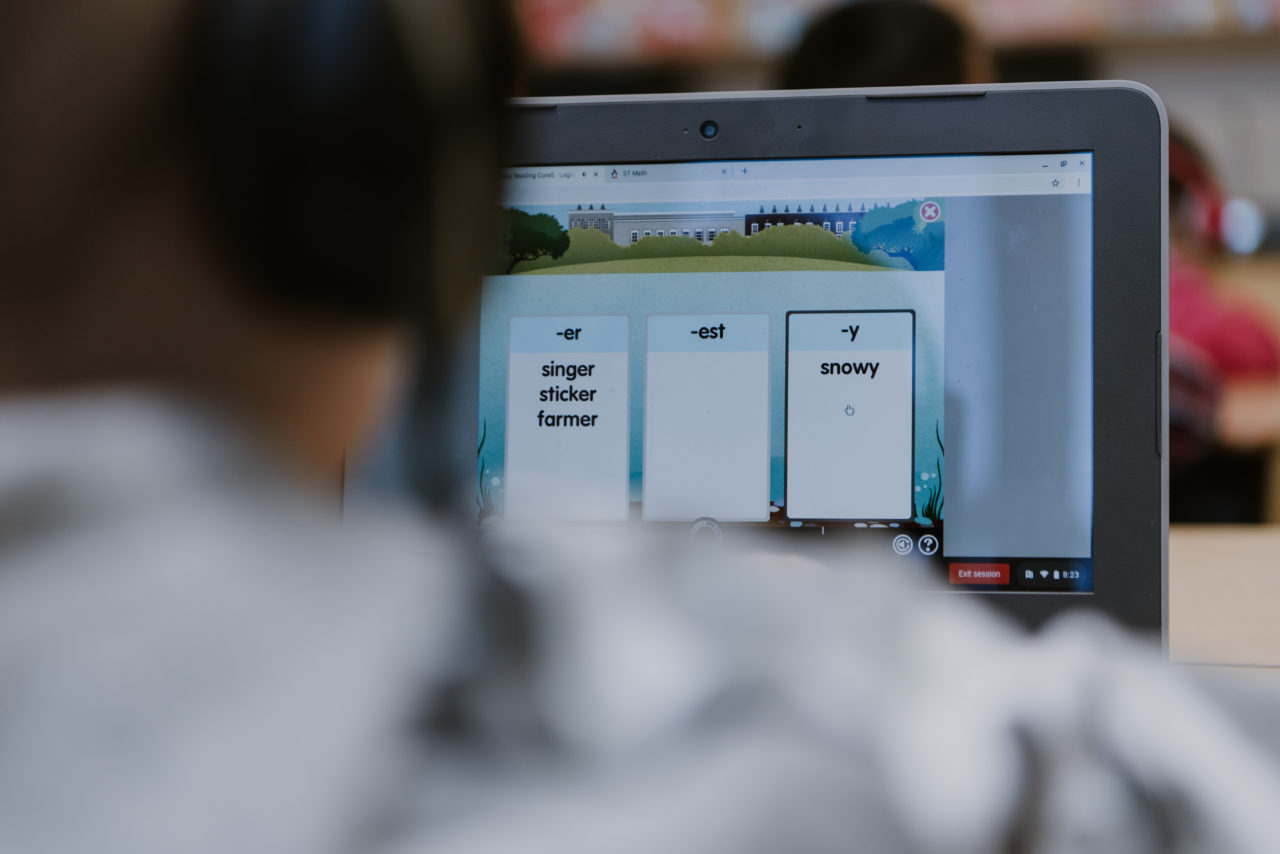

Thompson continues to plan for 100 percent of students back this fall, as does Greeley, but even then, there are backup plans, and those plans shouldn’t worry parents, Huckaby says. “We’ve learned a lot over the spring. We saw teachers do great things super quickly, and we are building on that skill in the event that we have to go online. What we want is online learning instead of pandemic learning.”

Greeley’s district officials are confident in their backup plan. “It forced us to address things along the lines of our goal of personalized learning for every student,” Myers says. “We will be in a much, much better place for remote learning. We figured out a lot of things to make it a better experience for the students.”

That included making specials such as art, music and physical education more meaningful, although that remains challenging. The district would also need to find ways to make learning independent at home without relying on students to shove their faces near a screen all day.

Myers says all school districts need to be ready for the prospect that they may be required to use virtual learning at some point during the year. The state could shut down schools, or counties could shut down certain districts or restrict them, or districts could decide to close individual schools.

“The governor point blank told us that,” she says. “He basically says it’s not if there’s an outbreak, it’s when, and we have to be prepared to go into remote learning at any point.”

Districts will offer an online option

All school districts will have some form of full online learning available, with only the PSD offering some skepticism as to how it would work.

“We are going to offer a fully remote learning option,” Myers says. “We don’t have the specifics, but we do have a plan in place. It will operate like a mini online school with teachers teaching at different grade levels.”

Thompson will likely use its online component already in place, but the district was exploring what it could look like and how to make it district-wide. “At minimum, we do have what we already have,” Huckaby says, “but we are also exploring options.”

RE-4 will offer an online option for all grades, even giving a chance for students to interact with other online peers and teachers. Students who choose to learn virtually would need to be self-motivated and have support from areas outside the district (although the district will offer support as well). Online learning will also hold students accountable, even if they are forced to go back to virtual. No more free rides, in other words.

PSD will also offer an online option for all grades for parents nervous about releasing their kids back to school, but the district admits it will be a challenge to find teachers for it if students are back in school.

The Poudre Global Academy (PGA) has offered hybrid instruction for a decade and won awards for it. “But those are kids who are there by their own volition,” Lambert says. “Now we recognize we have kids who don’t want to learn that way and teachers who don’t want to teach that way.”

So, tossing students into the PGA and expecting the staff to teach all of them is unrealistic, Lambert says. PSD was still working on a solution at press time.

School won’t be the same regardless of how it’s held

School won’t be the same regardless of how it’s held

School districts used the well-worn cliché, “new normal,” to describe what school will look like this fall. This means that even if districts have all of their students back in person for classes, it won’t be the same as it was before the coronavirus emerged.

How different? Well, for starters, districts hope to split students into “cohorts.” That’s already done to a large degree in elementary schools, as there are still grades split into classes, just like you remember. But that system erodes in middle school and vaporizes in high school.

And that doesn’t necessarily address hours between classes. “Even if you could break some of them into smaller groups, how do you maintain them in between classes?” Lambert says.

The prevailing idea is: groups, regardless of the grade, wouldn’t mingle with other groups, so combined gym classes, recesses or lunches won’t happen, at least not right away, Myers says. And they may see the same students in the same classes all day. It sounds complicated, and it is, but there are also obvious advantages.

“If there is an outbreak, maybe you could just send that class home and that teacher into quarantine,” Myers says, “and not send a whole school home.”

It’s also possible that students wouldn’t have to wear masks all day if they were in a small group and other precautions were taken, such as taking the temperatures of students. Administrators rolled their eyes in anticipation of telling kids to put their mask on all day, so any relief would be welcome for the staff and teachers as well as the students. Students would need to wear them during passing periods or in other situations where crowds are unavoidable. District 6 has a mask-making campaign for students who may not have them.

“We will have some extras on hand that we can provide if they can’t get them,” Myers says. “I would think most people have them by now.”

These plans will probably make a bigger impact than you might realize. Thompson, for instance, does not plan to serve breakfast and lunch in cafeterias, as that’s too many people together at one time, but it still will provide meals, so perhaps that means serving them outside when it’s warm enough and in several rooms in the winter. Students also may not be allowed to leave school for lunch, a common pre-COVID practice for high school students.

“It doesn’t make sense for students to leave and interact,” Myers says. “But are we going to let them eat in some communal areas?”

Playground structures may have to be closed, and recess may be too difficult to monitor. Would the schools, for instance, have to clean the structures in between classes?

Sports are also a big question. RE-4 has already said it would allow kids using a virtual model to participate in sports, but that’s if the districts can have them. Most of those decisions will be made by the Colorado High School Athletics Association and the governor’s office, and there were troubling trends even at the end of June, such as college football teams with players testing positive for the virus after a few practices. Attendance probably won’t be allowed regardless of the sport.

“We think there will be some sports back,” Myers says. “Non-contact sports, such as cross country, are probably a go, but we aren’t sure for contact sports. We believe kids have to have masks when they aren’t social distancing in places such as weight rooms, and we are looking to take some lead from colleges as well.”

District officials also recognize that many of these activities, and others, such as music, theater and physical education, offer important social structures, and so they will try to do what they can to maintain them, even during lunch and recess.

“We will start pretty tight,” Huckaby says, “and then open things up as we can.”

Districts are concerned about mental health as well as physical education

Social distancing, a lost year, virtual learning and a litany of anxiety-causing concerns from COVID-19 affected your kids as much as you, it turns out, and districts plumped up ways to watch for students’ mental health as a result, even as budgets were slashed across the state.

“Our school counselors and social workers will have to jump in and offer that next layer of support,” Huckaby says, “and quicker than in previous years.”

Teachers will need to be that first level, as they always are, and they are setting aside extra time this year to connect with kids, either virtually or in person. But those same teachers will need a bit more support as well, as the change and uncertainties add stress to their work lives (not to mention their other lives as well).

“It’s as high up there as the academics are in terms of getting students back,” Huckaby says.

Thompson officials tried to study the behavior of students in schools, says Tracy Stegall, executive director of teaching and learning for the district, and will try to bolster safe access to specific areas such as the library center, where troubled students may find safety.

“The attention of safe places has been a focus,” Stegall says. “Now we are trying to build those safe places across the buildings.”

That could mean “cozy corners” in elementary schools, for instance. The challenge, she says, is officials now need to know where students are at all times, so if schools can’t offer full-time access to those safe places, maybe they will allow students to bring a stuffed animal.

“We do want to keep the practices that have worked and in safe ways,” Stegall says.

In addition to maintaining services such as interventions for families and students struggling with serious problems, consultation and counseling, PSD will provide new services, such as additional training to staff and teachers to re-establish connections, offer educational opportunities for parents on how COVID may be impacting their children and interventions for students struggling with all the changing school models and ways to re-connect with their peers.

Transportation could be tricky

Transportation could be tricky

Here’s a riddle: How many kids can ride in a bus and remain socially distant?

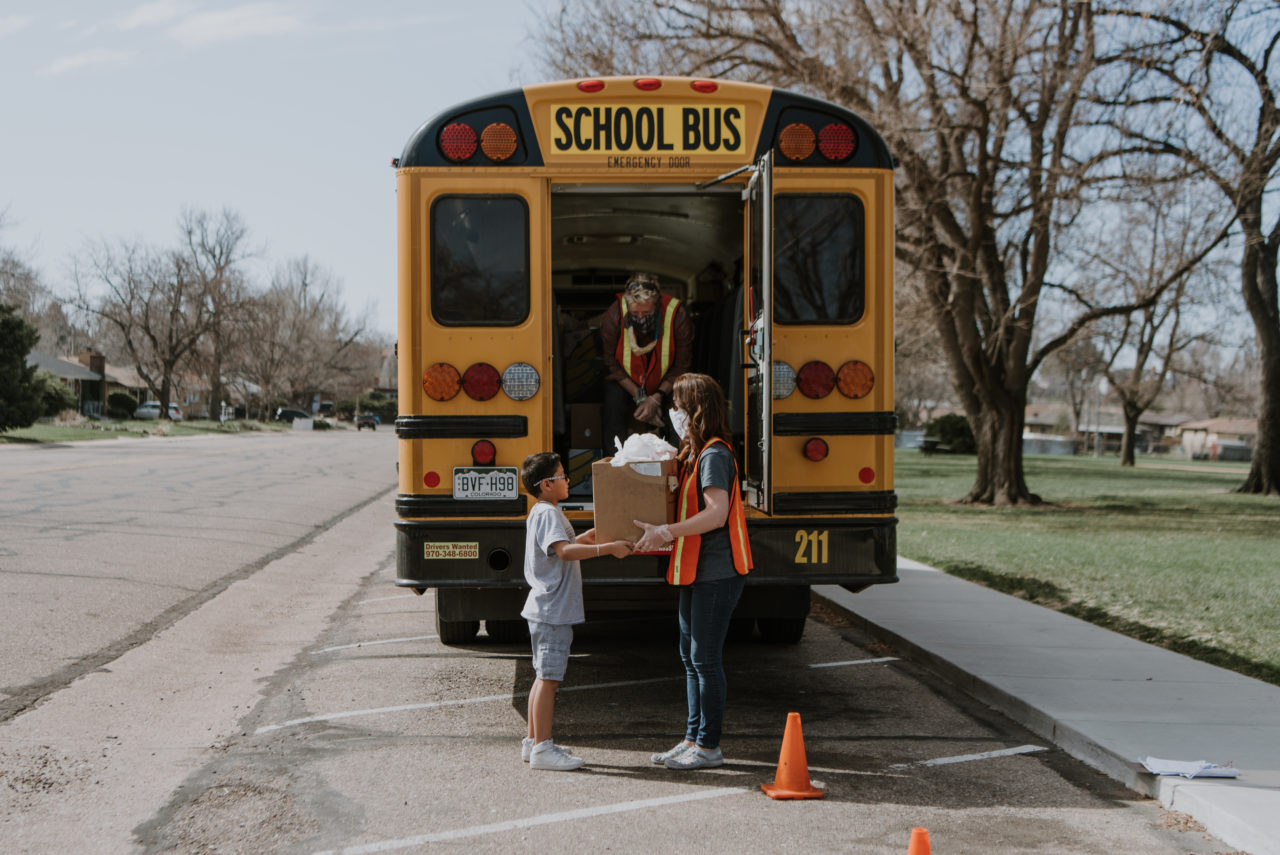

Well, as of June 24, the state has said 10, and that’s causing the kind of headaches that word problems caused you in math class. That’s right: Only 10 students for one standard-sized, 77-passenger school bus.

“Our buses are packed with three to a seat,” Myers says. “Are we really going to have to buy additional buses to transport kids?”

Probably not, given school budgets are already thin, thanks to the economic devastation caused by the coronavirus. So, it could mean districts will have to limit buses to students in foster families, with special needs or those the district considers homeless. That’s PSD’s plan if the ratio continues, and that would be a severe cutback, given that the district typically buses 14,000 students, or half its enrollment. The restrictions would reduce that number to 400.

It’s possible that the ratio could be increased to 22 students per bus, and if that happens, PSD would take applications from parents for a ride on the bus, likely those who receive free lunches and meet other low-income guidelines. It’s also likely other districts would follow that plan. In the meantime, PSD will offer ways to help families find carpools while acknowledging that if the ratio isn’t increased beyond 1:22, it will struggle.

“Can we help people organize ways to get to school? Of course, we can,” Lambert says. “Two years ago, I would not have said that. But now I think we can.”

What happens if someone gets sick?

Districts anticipate that schools will receive additional guidance from the state in this scenario, as no one really knows right now. As districts hinted at earlier, it could be possible to close one school and leave others open, or even leave a school open but quarantine students in cohorts if one in that group gets sick.

Schools will work on ways to contact trace someone who does fall ill or simply has a fever in the testing before class every day. Districts will work with their local county health departments and the governor’s office to determine if they can use a hybrid model or have 100 percent of students in the schools. They also expect those guidelines to change as the year goes on, for better or for worse.

“Just two weeks ago, we said we’d have just 50 percent of the students in a building at one time,” Huckaby said on June 19 of Thompson. “Now we are trying for 100 percent. So, things change all the time.”

All district officials stressed that their plans had contingencies in case there’s another outbreak or as things continue to improve.

“We will just have to see how it goes, right?” Myers says.