By Dan England | Photos by Sunshine Lady Photography

Nearly a decade ago, Armando Silva was 24 and hustling for jobs, when he had an idea.

He had finished painting a bear logo at the University of Northern Colorado, where he graduated with a fine arts degree, and he was looking for his next job as an artist. Armando had made somewhat of a name for himself in Greeley: He’d performed at the Greeley Arts Picnic painting and dancing, landed a couple speed-painting gigs and once played a mime who paints at an art show. But nothing had really stuck, and Silva was really more of a novelty: a young, well-spoken Mexican-American who could dance and paint fast and be available at schools when the administration wanted to inspire other Latinos to follow their dreams.

He knew downtown Greeley was trying to change its image as an ailing ghost-town to a place that could one day be nearly as hip as the downtowns in Fort Collins and Loveland. One avenue was to promote colorful murals on the sides of the area’s many old buildings, but that idea had fallen dormant after just a couple murals.

What if Silva did a mural? Greeley’s Downtown Development Authority liked the idea and agreed to pay him—not much, honestly, just something to cover the cost of materials and a few meals—to do one.

“I was a busker, really, just wanting to put myself out there,” Silva says. “That was me throwing anything at the wall and seeing if it would stick.”

Silva literally did that, throwing a bunch of color on a red brick wall in the center of downtown, near the Union Colony Civic Center (UCCC) and Lincoln Park, and, well, it stuck. The Einstein mural attracted the attention of Denver TV stations and helped rejuvenate the mural program. Today, the City of Greeley has 47 murals, if you include storm drains and the power transformer boxes, says Kim Snyder, who runs Greeley’s public art program.

“His dynamic style and painting technique really got it moving again,” Snyder says. “The spot he got on 9News for [the mural] was really good attention for the art scene in Greeley.”

The question most asked at that point, of course, was who was this guy? Silva got it. He didn’t really know at that point either.

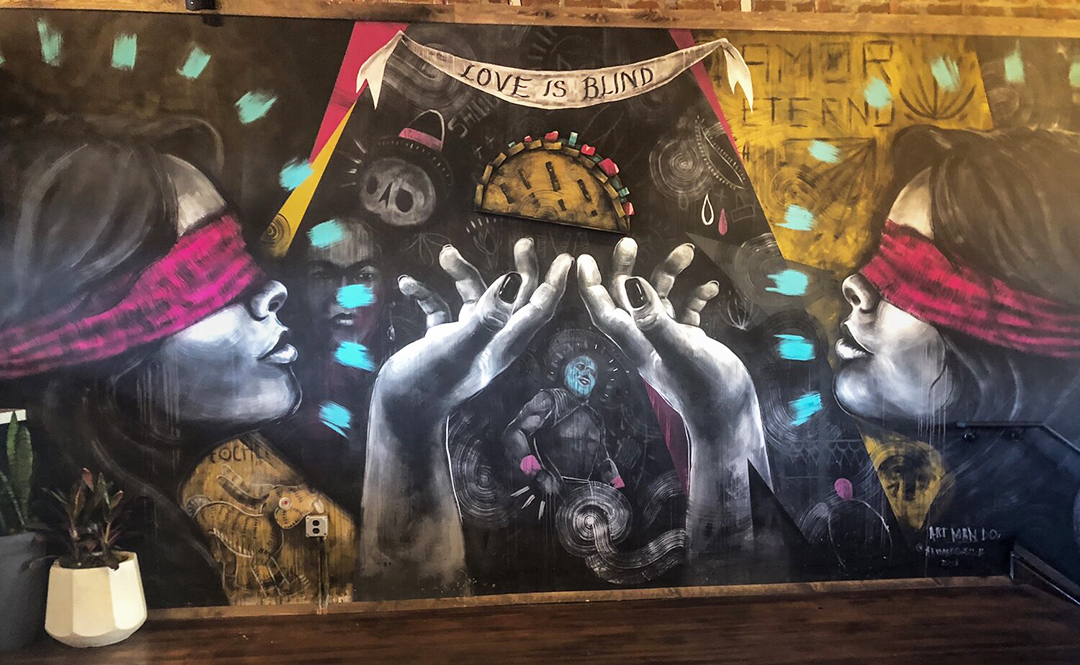

One of Silva’s murals, located at 920 A St., Greeley. | Photo courtesy of Armando Silva.

Einstein was also good for Silva, not just Greeley, as it got him noticed. It gave him a chance to prove himself, and once he did with other murals, painting jobs and speed-painting gigs, then businesses, parties, fundraisers, civic organizations such as the Greeley Philharmonic Orchestra, schools and even the Denver Broncos called on him to do his special brand of performance art.

His artwork takes up an entire wall at Luna’s Tacos and Tequila in downtown Greeley. In fact, he has four murals in downtown Greeley now, and his paintings hang in many bars, offices and gyms. Even if you don’t think you know him, you’ve at least seen his artwork.

“The Broncos, especially, really spoke to the kid in me,” he says. “The best part about it was that happened organically because of the work I was doing.”

But he is now 33. He is established, and he has taken that time afforded him as he got established to change and grow and do things that are important to him, not just the client, even if he still has to make concessions that entirely independent artists don’t have to make.

“But they want me to do what I can do,” Silva says. “That’s why they call me, and I want to do what’s best for the platform as well. I don’t want it to be just an aesthetic thing. How does it activate itself? I have to know what’s important so we can communicate the message and it becomes alive.”

Bear logo at the University of Northern Colorado

Salida del Sol Mural

Places to see his ART:

• Poder es Saber, Rodarte Center, 920 A St., Greeley

• Home, Apartments at Maddie, 8th Ave. and 16th St., Greeley

• Rise, Salida del Sol Academy, 111 E. 26th St., Greeley

• Sunrise Community Health Mural, 2930 11th Ave., Greeley

• Love Is Blind, Lunas Tacos and Tequila, 806 9th St., Greeley

• Courage, 8th Ave. and 7th St., Greeley

• Harris Elementary School, 501 E. Elizabeth St., Fort Collins

• Boulder Chamber of Commerce, 2440 Pearl St., Boulder

• The Lincoln Center, 417 W. Magnolia St., Fort Collins

In 2016, Silva attempted to become more of a, and there’s no easy way to say this, serious artist. He got a show at the Tointon Gallery in the UCCC, perhaps Greeley’s most well-known public gallery, a place where people hang accomplished artwork.

Silva saw it as a turning point, which made sense. He had a fine arts degree, remember, and by that point, he was the darling of Greeley who served on arts boards and was one of the stars of Greeley Unexpected for his decision to stay there instead of moving down to Denver.

So, he opened his own art gallery downtown and prepared to transition to a more typical fine arts career—the dream of most artists, says Silva, the way many musicians dream of their first record with a major label instead of playing nightclubs on the weekend. He would paint and hang artwork in his gallery, and people would come and buy them.

Only today, Silva admits he wasn’t ready, both financially and emotionally, for the change.

“I was leading people to a space that I didn’t want to be in,” Silva says. “Plus, the overhead was huge for what was essentially a storage space. I do think there’s something to isolating yourself and doing the work you want to do. You’re on your own. I was trying to find that discipline, but it wasn’t my dream.”

Giving up the studio wasn’t a failure, he says, but more of a way to find himself. And he likes what he discovered about himself. He is, in fact, a Mexican-American artist. “That was something I was shy about initially,” Silva says.

There’s little doubt that reticence benefited Silva in a way, he says, because he could present groups with an articulate Mexican without being confrontational or really even mildly overt about it, and because of that, white people who didn’t know any better would listen to him and maybe understand the true culture instead of one they’d seen, say, in a restaurant that served fajitas.

Silva was born in Sombrerete, Zacatecas, Mexico, before his family moved to Northern Colorado when he was 5. His dad is a successful car salesman. Silva began to slowly embrace that side of himself, and now it is a huge part of his work, both in the projects he takes on and what he paints.

“I’m pretty OK with saying that my work is inspired by Mexican folklore,” Silva says, “but I am looking for a contemporary voice in which to present it.”

That means he’s willing to paint those images for others, but he may also hope to influence what they want him to present. “That folklore is becoming a fabric of pop culture,” Silva says. “The Day of the Dead—what do you see? It’s the skulls. That’s very important, but there are a lot of other things about the culture. What can we do with that, and maybe present it in a different style?”

Lunas Mural

Silva embraces opportunities such as a collaboration with the Denver Botanic Gardens for Day of the Dead, or doing three paintings for the Lincoln Center in Fort Collins to enhance a Folklorico show (they still hang there today), or traveling to Oaxaca, Mexico, a rich, cultural city, and meeting with Mexico’s Secretary of Culture. That last trip may lead to a project that could connect Greeley, a city with a large Latino population, and the community in Oaxaca—an exploration of how Greeley resembles Oaxaca in many ways, even if it initially may not seem that way.

He’s also traveling to Granby to help the city celebrate Mexican-American culture, which is something he does now to “add context,” as he puts it, essentially helping communities do more than just putting up those skulls.

But he also wants to be known as more than a Mexican artist. After all, the Broncos didn’t hire him because he was Mexican (even if they were thrilled that his bilingual skills helped them connect with Latinos, a significant portion of the Broncos’ fan base). He does many projects that do not invoke his heritage, such as traveling to Baja California. Not to learn about culture; he’s going with the Denver Zoo to learn about stingrays for an exhibit that the zoo opens this year.

The wildlife exhibit mirrors his desire for any piece he creates, whether it’s a reflection of his Mexican heritage or not, to have a message behind it. “It’s to go experience the space,” he says, “and be authentic with the space as much as possible.”

That remains tricky as an artist who wants to honor his heritage but not, as he put it, “culturally appropriate” himself.

“People do want to support a Mexican-American artist,” he says, “whether that’s to bring in more sales so they will feel welcome or because they truly want to make that connection. Well, for me it’s a way to move beyond that. It’s an opportunity.”

Even so, if what someone is asking Silva to create feels like it’s heading in the direction of a cliché or, even worse, an exploitation, even if it’s unintentional, he will back away if he can’t change the minds of those hiring him. “I’m not shy about saying I’m not the guy,” he says.

It can still go the other way, too, when he hears the rare questions about why he’s not painting white people in his works. “They may say they didn’t want the Mexican stuff here,” Silva says. “But that’s just me. I’m an artist who is willing to engage and communicate with you.”

He’s 33, and that’s an age when someone should, as he put it, know what his tricks are, and he’s beginning to figure that out.

“It goes back to bringing in some of those traditional things I grew up with,” he says, “and having some sort of say in them, to connect the dots and work with different generations and give people a sense of home. But this time, on a grander scale.”